Genre Painting by Brian Shapiro

Two Jewish holidays particularly command us to be connected with our vast history. Most notably the Passover Haggadah demands that we feel as if we too went out of Egypt with the Jewish masses. Less obvious is Tisha b’Av.But if the destruction of our two Temples and the subsequent Jewish communal disasters are to be properly commemorated, we must somehow transform our feelings into a personal loss. Each oppression, each murder, each disgrace must feel like it happened to our family just yesterday.

This kind of empathy is central to Jewish consciousness. As a community, what happens to each and every one of us ultimately affects us all. We are a living people with an acute memory enforced by the commandment to remember.

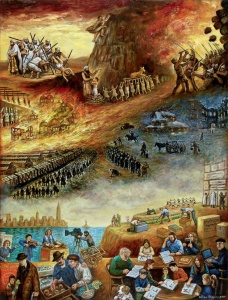

Brian Shapiro’s painting, Generations, is an ambitious attempt at placing his personal contemporary life within this vast canvas of memory. His painting chronologically “begins” with the Binding of Isaac and ends with the artist today, all on one 44” x 58” canvas. This kind of pictorial program spanning 3800 years in one visual field is unheard of in Western art. The closest example of Jewish art that approximates this span can be found in the 14th century illuminated Spanish haggadot that feature many pages of images starting with creation and finally ending with contemporary medieval genre scenes of Passover preparation. These medieval images span a vast history that is singularly impersonal and totally based on Torah narratives and commandments.

Shapiro begins with the present in the lower right corner, his family and friends learning Torah, Talmud and, for the youngest, the aleph-beis. This strata of the painting is thematically and pictorially linked with the good Jewish life in America. There are small hints of struggle with a demonstration for trade unions, but overwhelming the images are positive; filmmaking, musicians and push-carts with bagels and fish on ice. Immediately behind them and yet pictorially in the same space is contemporary Israel; land of the Western Wall, agriculture and hora dancers.

As we move up the painting the tone changes dramatically. The scenes become monochromatically dark with blue, black and white dominating. Countless masses of Jews disembark from the trains to barracks in the concentration camps. A brutal forced march transitions to the grim reality of a snowy night in the shtetl, a place of faith amidst darkness. In the fiery upper section an entire town of synagogues goes up in flames. This is but a prelude to a violent ancient history: the Temple is destroyed, the Golden Calf is worshiped, Joseph is thrown into the pit by his brothers and Isaac is tied up and ready to be slaughtered. Surmounting the entire spectacle Moses climbs up the mountain to talk to God. In a rather curious way the artist seems to link the top and bottom of the painting. In America the artist and his family seek out God in Torah study while at the top of the painting, at the beginning of Jewish history, Moses too seeks to know God’s will and commandments.

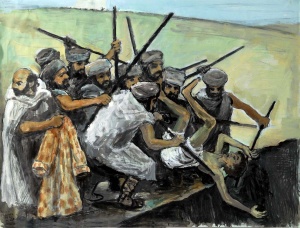

In three preparatory studies Shapiro reveals himself as a highly accomplished draftsman and narrative artist. While the Binding of Isaac and Moses Climbing the Mountain are certainly impressive, Joseph’s Brothers is spectacular. The jumble of furious brothers are expertly composed in groups of three. The sinister figure in white holding the ill-fated multi-colored coat and guiltily looking off to the left begins another set of three white garments culminating with the white shorts of Joseph, upside down and about to plunge into the pit. The intensity of brotherly hate and violence has seldom been captured so convincingly.

Brian Shapiro is at home in this world, the world of the down-to-earth. He is a consummate Jewish genre painter, comfortable with seemingly every aspect of recent contemporary life. His long career includes countless oil paintings of Hudson River landscapes, New York cityscapes as well as many commissioned single and group portraits.

Additionally he has an unprecedented series of paintings depicting behind the scenes movie making in Hollywood that earned him exhibitions in the Smithsonian Institution in Los Angeles and a first ever show at the Motion Picture Academy.

His series of Jerusalem cityscapes include many highly detailed views of bar mitzvahs at the Kotel (many commissioned by individual families), views all around the Temple Mount and atmospheric old alleys and streets of Jerusalem.

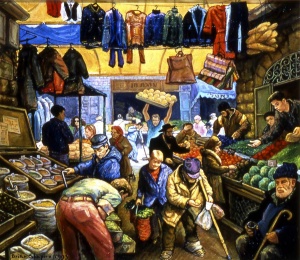

In an unexpected way Shapiro’s claustrophobic depiction of the Machane Yehuda market is a tour-de-force of genre painting. He frames the painting with a vegetable merchant on the right contrasted with the spice seller on the left. Through this scaffold flows every kind of customer imaginable, a hasid, an old lady, a beggar and a local Jerusalemite shopping for the day’s groceries. As we are drawn into the middle distance of the market we see a tray of freshly baked breads carried aloft by a burly baker. All the bustle and human activity inherent in the market is summoned forth in this vibrant image, every gesture telling its own familiar story. Even the jackets and pants for sale strung across the top reverberate with the humanity and vibrant atmosphere that characterizes this corner of Jerusalem.

For the past 13 years his work has concentrated increasingly on American Jewish life, from the New York Israel Day Parade to many joyous synagogue interiors depicting the Sabbath and holidays celebrations. Notably his series on 770, the Lubavitcher World Headquarters, has revealed an expressionistic side to Shapiro’s temperament.

Talk shows off Shapiro’s compositional skills to lead us to deeper meaning, framing the tallis-clad conversationalists with two men in black. The revealing contrasts between two bearded men in fedoras and the two men in tallis and tefillin allows one to contemplate the multiple paths to prayer open to both married and unmarried men.

On yet another level Phylacteries is a monument to an everyday mitzvah. The majestic triangular shape of the white tallis frames a pensive head crowned by his tefillin shel rosh. As he recites his prayers, eyes closed in concentration, the strength of faith is expressed in his massive arm wrapped in the black straps of his tefillin shel yad. His big beefy arm, constrained and yet strengthened by the mitzvah itself is a dramatic exposition of how Jewish men are bound and wedded to God daily. This is a simple, powerful and direct genre painting that goes to the heart of a central commandment.

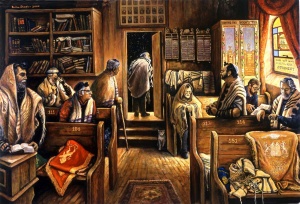

Shapiro’s concern with Jewish history in the context of his own history is perhaps most movingly elucidated in The Tenth Man. This 6’ by 10’ painting realistically sums up much of recent Jewish history. Set in an imaginary downstairs beis midrash with echoes of his grandparent’s shul in Rochester, New York, the subject is emblematic of the sad reality of many failing communities, waiting for the 10th man to be able to start morning services. The genius of genre painting is that it can narrate its message through the oddest assortment of details, all of which add up to making a coherent vision.

The four men on the left are all facing the same direction following the searching gaze of the rabbi standing in the doorway. Their collective gaze leads the viewer literally out of the painting into the mysteriously black of a star-filled sky. It is as if this little congregation has found itself on the moon with no Jews in sight. Similarly the right side is one of dissonant hopelessness, each man in his own thoughts waiting for the inevitable. The shul is littered with communal disarray; mismatched pews, odd Torah covers and old tallisim scattered here and there, a shul cat patiently awaiting a bowl of milk and finally the bookcase a jumble of worn-out volumes. The figure on the extreme right sums up the situation, glancing impatiently as his watch it is becoming clear to all that there will be no minyan today.

Genre Painting takes the details of the everyday and, when sensitively applied to subjects that the artist really cares about, can elevate the ordinary into the extraordinary. In the hands of Brian Shapiro ordinary Jewish life finds itself in the realm of the sublime.

Generations

Genre Painting by Brian Shapiro

brianshapiroart.com