Finding Moses: Part I

As the year draws to a close we have the book of Deuteronomy before us week after week, reviewing many halachos and reminding us of our harrowing trek through the wilderness. Moshe Rabbeinu is the stern narrator, guiding us to the very edge of the Promised Land, a final step he will never take. He pleads with God to let him enter the Land to no avail.

Finally, “Moses, servant of Hashem, died there, in the land of Moab, by the mouth of Hashem. And He buried him in the depression, in the land of Moab, opposite Beth-peor, and no one knows his burial place to this day” (Deut. 34:5). We complete our reading of the Torah with tears in our eyes for our faithful teacher, prophet and leader, whose life seems to end in angst and frustration. What was the inner life of our brave and tenacious leader?

He was everywhere and then mysteriously disappeared in early Jewish Art. In all of the ancient synagogue mosaics that have survived within the first 500 years of the Common Era, not one depicts Moses. And yet in the Dura Europos synagogue murals, created around 235 CE in what is now Syria, we see Moses depicted no less than eight times, easily the most represented figure in all the 28 narratives depicted. We see his rescue from the Nile by Pharaoh’s daughter in extensive images at Dura featuring Pharaoh, his royal court, the midwives, Yocheved and Miriam as well as a mysterious female figure fetching the baby Moses from his floating basket. Higher up on the synagogue wall multiple images of Moses are seen; heroically leading us out of Egypt, parting the sea and bringing the sea back to destroy the Egyptian army. Further along he proudly presides and towers over the Miraculous Well (Numbers 21:16-20) that sustained us after Miriam dies. Moses sustains us and then, in this ancient visual narrative, disappears. His poignant death is not even alluded to.

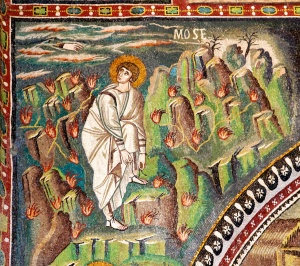

In Ravenna, Italy there flourished a school of Christian mosaic decoration between the 5th to 7th centuries that have yet to be surpassed in beauty and opulence. These churches and monuments formed the capital of the Byzantine Church in Italy, most notably the Basilica of San Vitale (548). These extensive and lush mosaics in the polygonal apse (altar) depict the Empress Theodora on one side and the Emperor Justinian on he other. Immediately adjacent to them are the biblical episodes of Abraham and the Three Angels and the Sacrifice of Isaac opposite the sacrifices of Abel and Melchizedech to God. Significantly, Moses is prominently featured three times. He is tenderly guarding his father-in-law’s sheep and right above that is removing his sandals before what appears to be the Burning Bush conflated with the fiery Mountain of Revelation. On the other side is Moses Accepting the Law from the Hand of God. In each image Moses is smiling and clean-shaven, depicted with a halo and in typical Byzantine Roman garb that is, for that matter, much like many of the figures in Dura Europos three hundred years earlier.

While for us these narrative episodes depict the beginning of our redemption as a people and the Covenant at Sinai, for Byzantine Christians the meaning was considerably more complex, almost certainly colored by the interpretations of typology. This form of Christian biblical analysis seeks to synthesize events in the Hebrew bible with the Christian scriptures, notable the belief that much of the Tanach is but an allegory that predicts the life of Jesus. Therefore Moses tending sheep foreshadows Jesus as the Good Shepherd, a humble Moses called by God predicts Jesus calling his humble disciples and the giving of the Law at Sinai reflects the new Christian covenant. This was a prominent form of Christian exegesis to give Jewish subjects an explicit Christian meaning from the time of the early Church, flourishing in the Middle Ages and prevalent up through the Protestant Reformation. Parenthetically it should be noted that Jews have used typology as a means of exegesis from the time of the Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael, a 3rd century midrash on Exodus, not to mention the fact that the Ramban was quite fond of this method of analysis based on the maxim, “ma’aseh avot siman levanim.” But one example of this is on the verse: “’And Jacob lived in the land of Egypt 17 years…’ that Jacob’s descent into Egypt alludes to our present exile at the hand of the ‘fourth beast,’ which represents Rome” (Ramban on Genesis 47:28). The simple faith of Moses here depicted does not even hint at his tumultuous past nor the burdens of leading a stiff-necked people.

Perhaps the most extensive depictions of Moses can be found in many of the Haggadot of 14th century Spain. While both the Ryland’s Haggadah and the Golden Haggadah depict the events leading up to the Exodus in great detail, in the vast majority of images Moses is simply going through the motions of the narrative that we have either from the Torah or the Haggadah itself and therefore little is revealed about him that we don’t already know textually. There is much to be gleaned from these images about the meaning of the plagues, the hardness of Pharaoh’s heart and even, at least in the Golden Haggadah, the role of women in the Exodus. But practically nothing about Moses himself. That is, with one exception, i.e. “Crossing the Sea and the Destruction of Pharaoh’s Army” in the Golden Haggadah.

In the next to last illuminated page the Egyptian army pursues the Hebrews on the right while on the left we see Moses and the Children of Israel just in front of the drowning Egyptians. Everyone is facing away and making good their escape from the sea except Moses. He casts a sorrowful glance backwards to the drowned soldiers and horses struggling in the midst of the sea. While the gesture of his right hand crossing over his body toward them should be construed as bringing the sea down upon them, this same gesture seems empathetic, reaching out to somehow mitigate their terrible fate. Moses in a rare moment of introspection here does not triumph in the death of our enemies and seems to mourn that it was necessary.

The fact that the Renaissance was deeply interested in the role of Moses is shown by the extensive cycle of paintings in the Pope’s private sanctuary, the Sistine Chapel (1482). Along the lower section of the long walls of the rectangular chapel are two series of very large frescos (each 11’ X 18’). Six paintings depicting the life of Jesus are opposite six paintings depicting the life of Moses including: Moses’ Return to Egypt, The Trials of Moses, Crossing the Red Sea, Getting the Law and the Golden Calf, Punishment of Korah and the Last Days of Moses. The predominance of the figure of Moses depicted by such major Renaissance artists here as Perugino, Rosselli, Signorelli and Botticelli should not be surprising since he is considered by Christian theologians to be the principle typology of Jesus, as is clearly expressed in the juxtaposition of these works. While in these images Moses is repeatedly depicted as the calm and stern lawgiver patiently going through the paces of the narrative, there is one extraordinary exception. In The Last Days of Moses attributed to Luca Signorelli, the entire upper half of the fresco depicts the sorrowful Moses being shown the Promised Land, coming down from the mountain to give his staff of leadership to Joshua and finally, his death and the mourning of the people around his body. This is one of the very few images of the final days of Moses’ life in the history of art up to the 20th century.

Michelangelo’s famous sculpture of Moses (1515) in San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome is in some ways unique in that it harkens back to an anachronistic depiction of the great leader with horns. Neither the mosaics at Ravenna (548) nor the Renaissance frescos (1482) in the Sistine Chapel show Moses with horns, a depiction that mainly flourished in medieval representations reflected by Jerome’s Latin Vulgate (405) translation of keren to mean horns rather than rays of light. Ruth Mellinkoff’s analysis of the “The Horned Moses in Medieval Art and Thought” (1970) argues that Jerome’s translation was neither a mistake nor an anti-Semitic slur, rather it represented an expression of honor and power common in late antique thought denoting only a metaphorical expression and never a physical manifestation. Of course the original intention of Jerome’s translation was unable to control the eventual anti-Semitic images of Moses with horns that flowed from it throughout the Middle Ages. Nonetheless, we ought to understand Michelangelo’s Moses as depicting a prophet of power and honor, as indeed the pose and demeanor of the marble statue majestically does. This is highly likely his intention since the sculpture was the centerpiece of the massive tomb of Pope Julius II, Michelangelo’s patron of the Sistine Chapel, not someone to be associated with any kind of negative figure. Aside from the much appreciated implications of this heroic figure, sagacious and ready to spring into action, we learn little about Moses’ interior life and struggles from Michelangelo. For that we will have to look to Rembrandt and, in the modern age, the brilliant works of Marc Chagall in our next review of Finding Moses.