Envisioning Maps

God commands Ezekiel to make a map; “take a brick and put it in front of you, and incise on it a city, Jerusalem. Set up a siege against it… This shall be an omen for the House of Israel” (Ezekiel 4:1-3). This map became a symbolic reality, a graphic tool used to convince the Jews that their precious city could indeed be destroyed as punishment for their sins.

Sadly it did not work and Jerusalem, along with the First Temple, were destroyed. Nonetheless we have been making maps ever since.

The Rambam attached a map of the borders of Eretz Israel to one of his responsa illustrating the fact that sometimes the specifics of a map supersede mere words. Not long after him Jews were active in making portolano maps, rather accurate navigational charts of the Mediterranean. The most famous of Jewish map makers was Abraham Cresques (d. 1387) who was the court cartographer for Pedro IV of Aragon and skillfully crafted maps of the entire known world. During the Middle Ages the symbolic use of maps flourished showing Jerusalem as the center of the universe surrounded by the Holy Land, reflecting the prevailing world view of both Christians and Jews. The first printed map of Eretz Israel in Hebrew is found in the 1695 Amsterdam Haggadah, an elegant example of the use of maps to concretize the narrative of the Exodus and the conquest of Israel by the Jews. Seeing is believing.

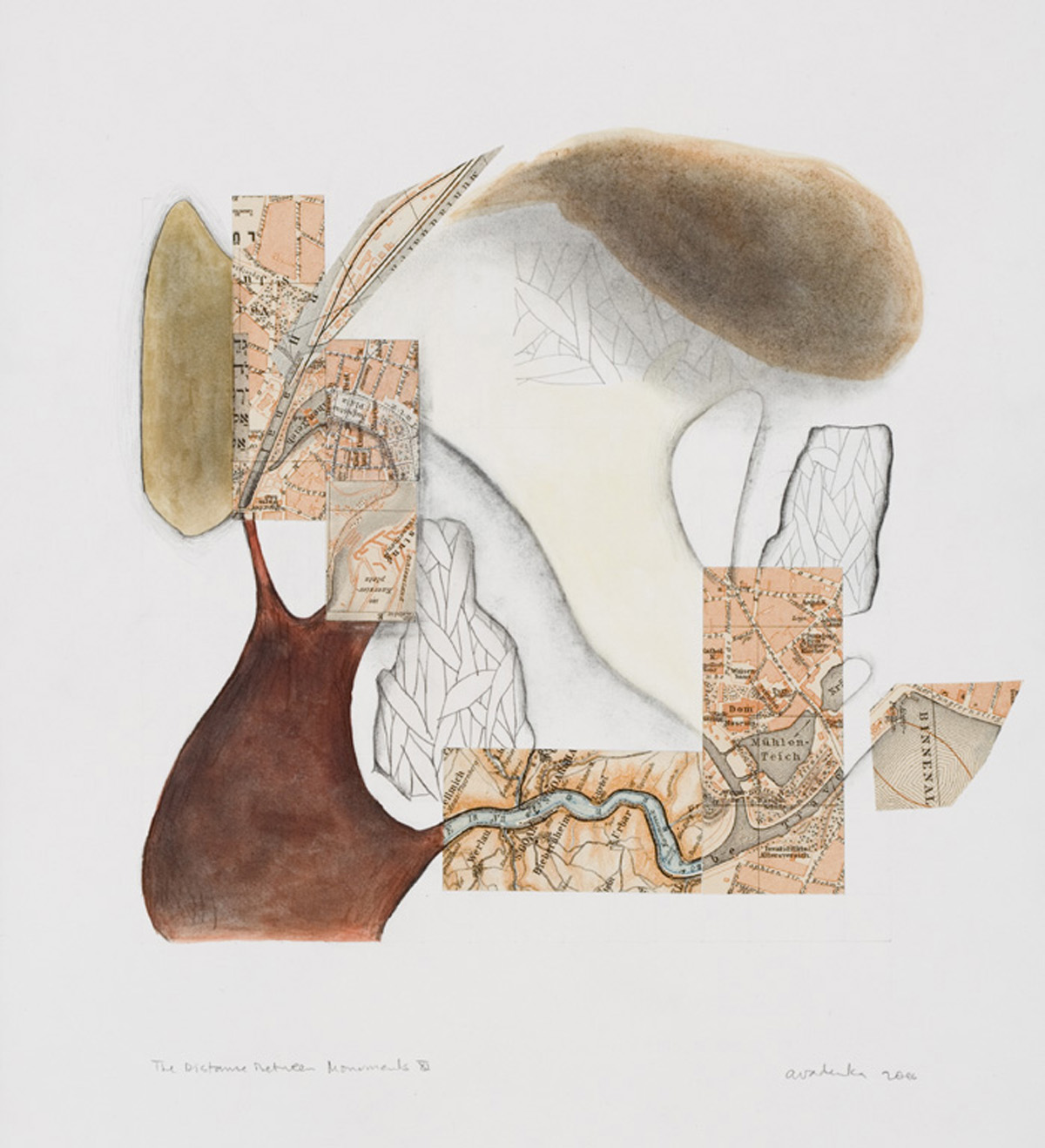

Against this background Envisioning Maps at the Hebrew Union College Museum presents us with contemporary visions by 33 artists of maps as active subjects in the creation of visual art. The maps in this exhibition are used in an exhilarating assortment of ways, exploring the complexity of Jewish life, history and thought. Some invoke a symbolic approach to Jewish history such as book artist and printmaker Lynne Avadenka’s The Distance Between Monuments XI (2006). In this mixed media collage she uses fragments of maps from a pre-World War I Baedeker guidebook from Leipzig, Germany integrated with her own drawing and additional fragments from a Hebrew-German grammar book to create an imaginary mapscape. This lyrical abstract composition poignantly depicts a Germany that no longer exists and, by extension, its Jewish population that was ruthlessly exterminated, rendering history and memory into a seamless aesthetic. Its beauty coexists uneasily with the tragic reality it is based on.

Not unexpectedly, the Holocaust is a subject that is easily explored with maps. William Kentridge superimposes a city grid with neighborhoods outlined in red over a bleak barren landscape in Waldsee 1944: Budapest/Soweto (2003). The fictional town of Waldsee (invented by the Nazis as a ruse to encourage the Jews to go along with deportations from Hungary) is equated with the segregationist town planning of Soweto, created to ghettoize Johannesburg, South African blacks. Additionally Kentridge’s deep perspective landscape of desolation forms a tension-filled dialectic with the graphic vertical flatness of the superimposed map grid casting maps as a necessary but deeply flawed way of experiencing a political reality.

Susan Erony re-experiences the cartological reality of the killing machines in Map (1992) as she photographed and collaged maps shown at the contemporary Buchenwald concentration camp exhibitions, piecing them together with texts from the German industrial barons who benefited from the abundant slave labor the camps provided. The proliferation of concentration camps depicted in her black and white photographs dramatically embedded in the black tar-like surface evokes a geographical memorial to the victims of Hitler’s industrial murderers.

A totally different take on mapping is explored by Karen Gunderson who looks up instead of down and produced Constellation 4; Copenhagen, N, 10.01, 1943 (2004). The all black painting pierced by various sized dots of white represents the night sky on October 1, 1943 when the Danish population banded together and provided refuge to its Jewish population; within a month ferrying 95% of them to Sweden in clandestine nocturnal operations. This conceptual work references one of the best known children’s books on the Holocaust that deals with the rescue of the Danish Jews, Number the Stars by Lois Lowry (1989) that uses Psalm 147; “He counts the number of stars, to all of them He assigns names…” as the theme of hope that God has not forgotten his Children in their most desperate hour.

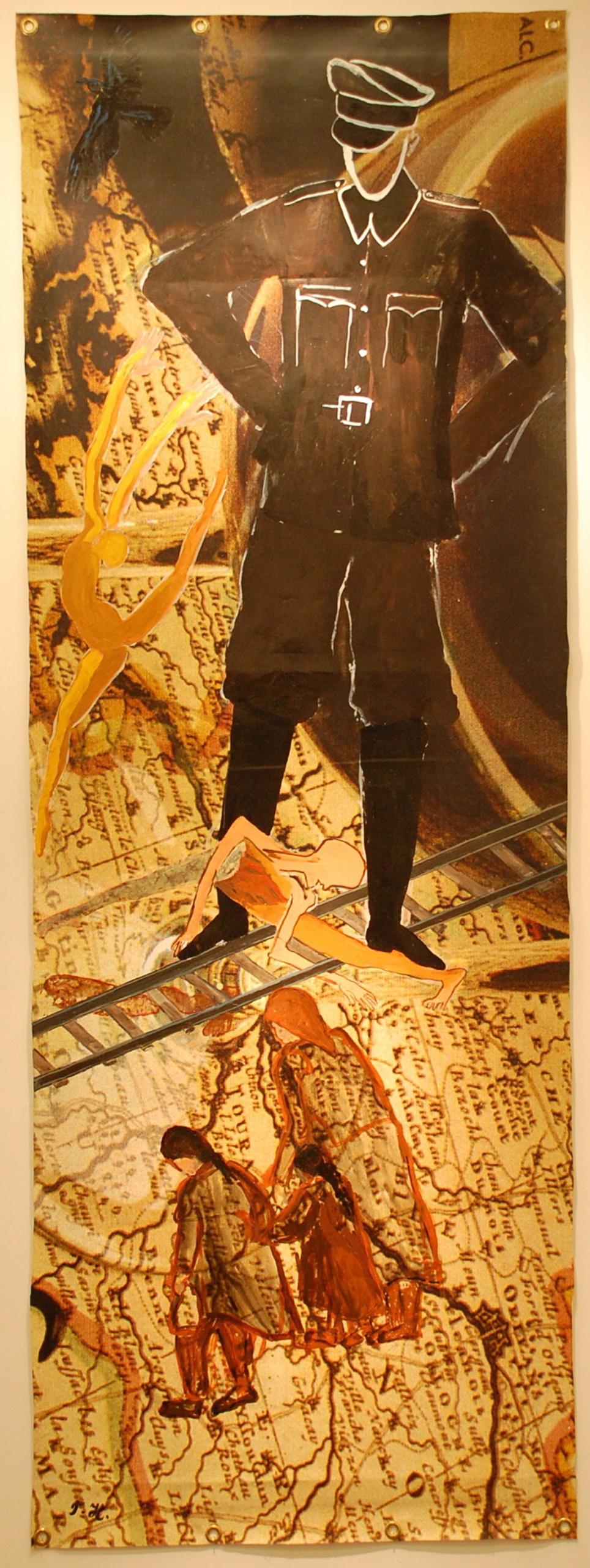

Across the gallery from this poignant skychart a vision of horror occupies an entire wall. Tamar Hirschl’s Exodus II (2000), an 8’ by 3’ mural, depicts a simple, riveting image of an SS officer standing bestride a European map, a rail line supporting his heinous outline. Figures incongruously flail, dance and struggle below, oblivious of the terrifying visage that hovers over their fate. The incoherent details the map provides allows it to represent all of Europe, just as one figure represents the entire Nazi killing machine. It is one of the most powerful images in the entire exhibition.

Across the gallery from this poignant skychart a vision of horror occupies an entire wall. Tamar Hirschl’s Exodus II (2000), an 8’ by 3’ mural, depicts a simple, riveting image of an SS officer standing bestride a European map, a rail line supporting his heinous outline. Figures incongruously flail, dance and struggle below, oblivious of the terrifying visage that hovers over their fate. The incoherent details the map provides allows it to represent all of Europe, just as one figure represents the entire Nazi killing machine. It is one of the most powerful images in the entire exhibition.

A number of these artists use the maps as an elemental form that changes meaning through its contextualization. Archie Granot’s Ketubah of Rebecca Schaeffer and Michael Moldovan (1999) utilizes his well-known multilayered papercut techniques to exploit the cloverleaf shape of the classic world map showing Jerusalem as the center of the universe. Here the ketubbah text becomes the symbolic world of the new couple, transforming a theological shape into marital commitment and meaning.

Multiple layers also play a central part in Maty Grunberg’s Aging: The State of Israel (2003). The topography of the Land of Israel is chronicled in ten or more sheets of cut out paper placed over one another projecting down into the ground, leaving a vivid depiction of the depths of the Kinneret and Dead Sea. While subterranean geography evokes the Land’s ancient history it is the multi-colored lines that squiggle helter-skelter on the top surface that delineate its myriad political borders real and imagined since 1947. Just as time, weight loss and gain, stress and excess take their toll on the human face, so too Grunberg imagines the surface of Israel scarred and etched by her political history.

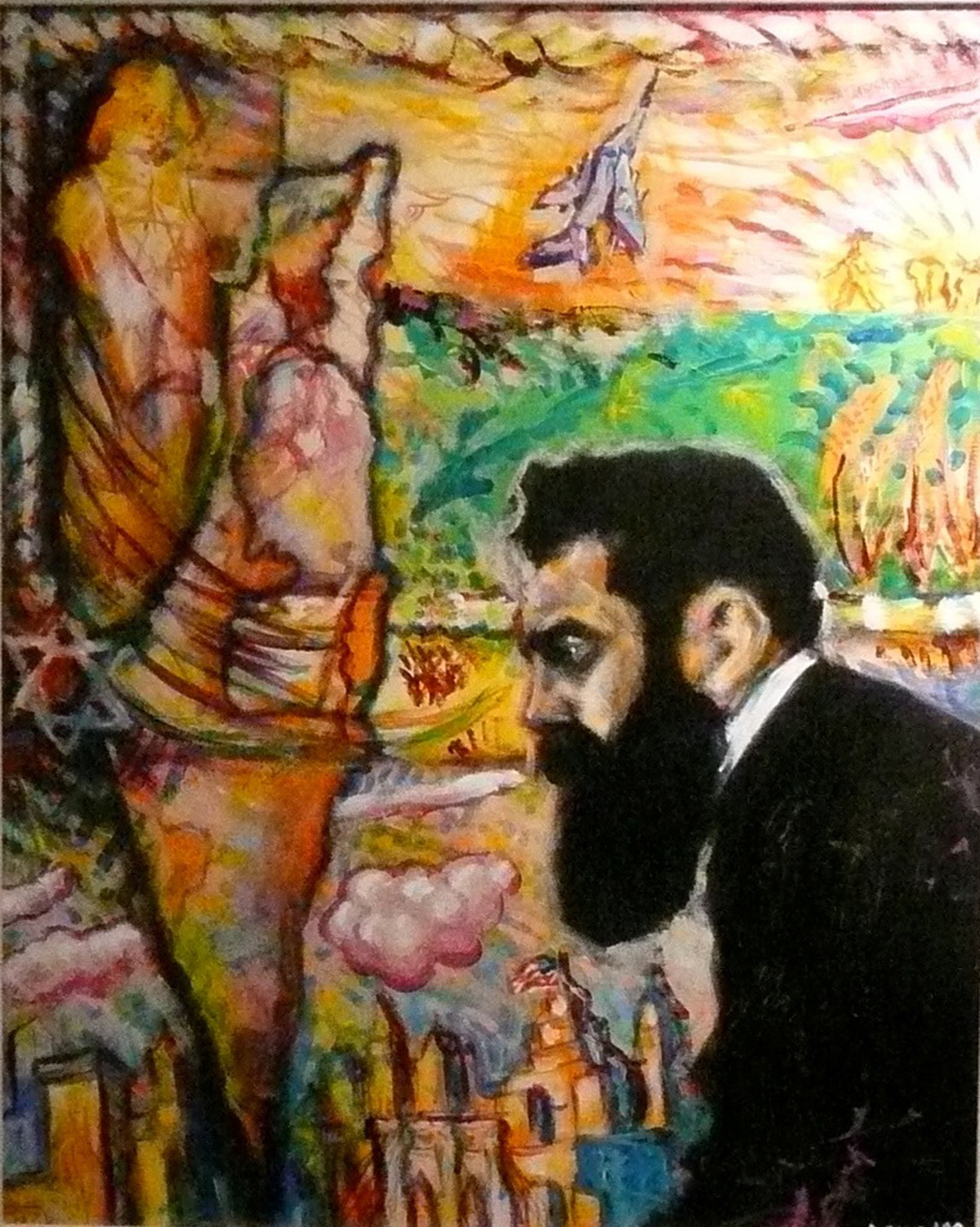

Archie Rand sees a map of the State of Israel as but part of a hallucinatory vision of the Zionist Theodor Herzl in Zionism: the Sequel (1998). Opposite a black and white rendering of the iconic profile of Herzl a visceral map of Israel dominates the left side of the canvas, supported by a Jewish muse and defended by an IDF fighter jet. This lurid green, yellow, pink and red vision seems to rise out of the New York skyline identified by an unmistakable Brooklyn Bridge. Herzl’s Zionist vision has been extended so that the confidence that the Jewish people needed as they demanded a state of their own has now morphed into the assertion that Jews everywhere, even outside the land, must stand proud and confident of their worth and creativity

Archie Rand sees a map of the State of Israel as but part of a hallucinatory vision of the Zionist Theodor Herzl in Zionism: the Sequel (1998). Opposite a black and white rendering of the iconic profile of Herzl a visceral map of Israel dominates the left side of the canvas, supported by a Jewish muse and defended by an IDF fighter jet. This lurid green, yellow, pink and red vision seems to rise out of the New York skyline identified by an unmistakable Brooklyn Bridge. Herzl’s Zionist vision has been extended so that the confidence that the Jewish people needed as they demanded a state of their own has now morphed into the assertion that Jews everywhere, even outside the land, must stand proud and confident of their worth and creativity

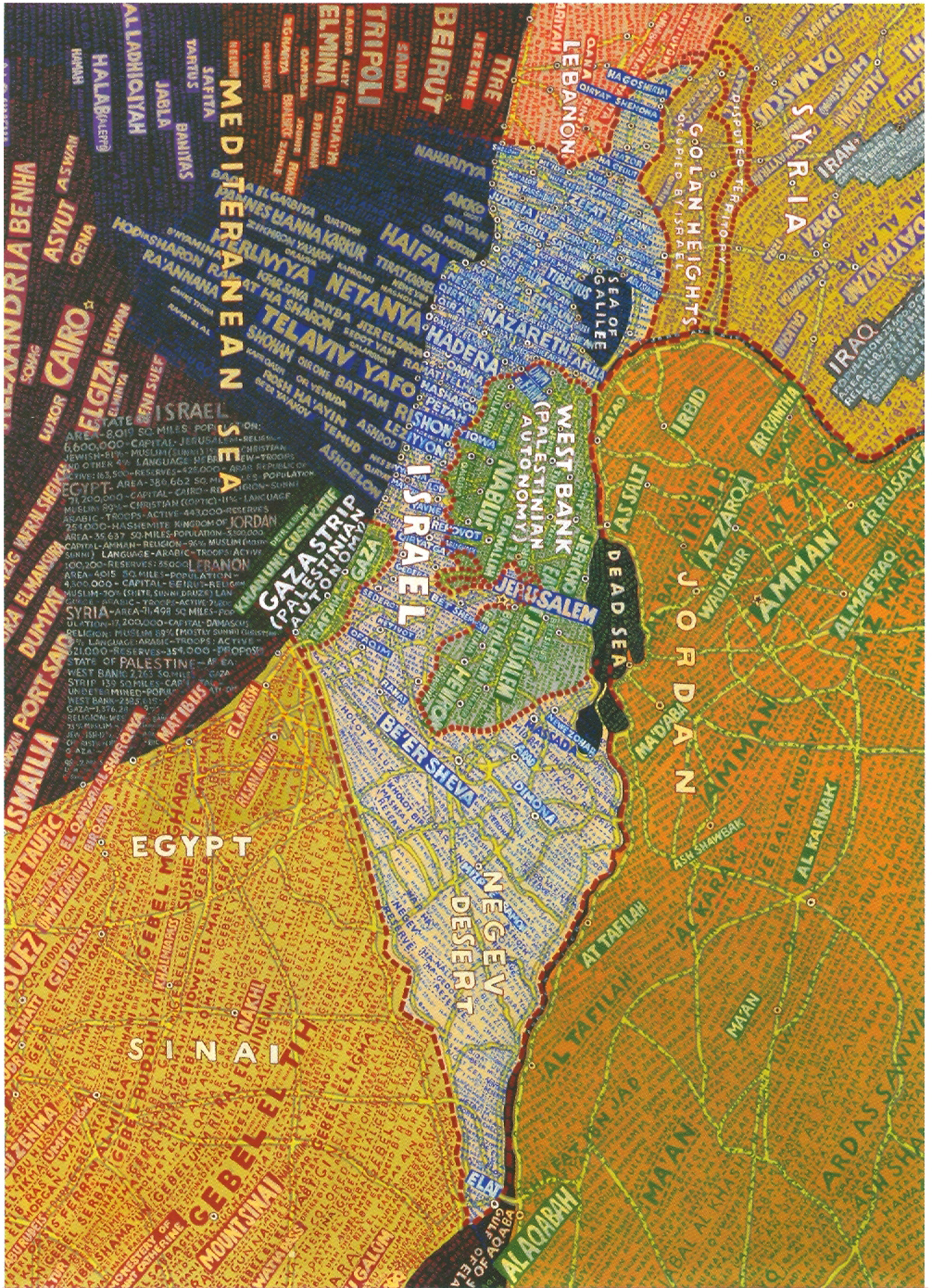

Two artists explore yet another elemental aspect of maps, their textual place names that define maps as charts of inhabited places, combining the visual with textual information. Paula Scher’s Israel (2007) presents an overload of information as she constructs an image of Israel and its neighbors totally dominated by their place names that define its inhabitants. Not one inch is empty of human presence, rather a cacophony of languages arises to attest to the claims, counter-claims, disputes and wars that make up this corner of the world. Perhaps more than most works in this exhibition the conceptual material of maps (borders, outlines, roads, place names, etc.) is here transformed into an aesthetic device that reverberates with meaning and beauty. The way the names of the coastal cities flow horizontally inland, contrasted with the vertical names of more distant coastal and river non-Israeli locations (Port Said, Cairo, Luxor, Beirut, Tripoli) emphasizes the tense conflicts just as textual direction and color changes define the borders between Israel and Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Egypt. Text and its direction aesthetically defines the political borders of the map turning the image into a cauldron of potential violence.

Two artists explore yet another elemental aspect of maps, their textual place names that define maps as charts of inhabited places, combining the visual with textual information. Paula Scher’s Israel (2007) presents an overload of information as she constructs an image of Israel and its neighbors totally dominated by their place names that define its inhabitants. Not one inch is empty of human presence, rather a cacophony of languages arises to attest to the claims, counter-claims, disputes and wars that make up this corner of the world. Perhaps more than most works in this exhibition the conceptual material of maps (borders, outlines, roads, place names, etc.) is here transformed into an aesthetic device that reverberates with meaning and beauty. The way the names of the coastal cities flow horizontally inland, contrasted with the vertical names of more distant coastal and river non-Israeli locations (Port Said, Cairo, Luxor, Beirut, Tripoli) emphasizes the tense conflicts just as textual direction and color changes define the borders between Israel and Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Egypt. Text and its direction aesthetically defines the political borders of the map turning the image into a cauldron of potential violence.

The use of text to redefine a well-known map image is no more evident that in Neu-York (2000) by Melissa Gould. In what at first seems to be a vintage 1945 map of Manhattan, upon closer inspection yields the shock that all the familiar streets, intersections, neighborhoods and monuments have been renamed in German bearing uncomfortable resemblance to real places in Berlin. It is a horrific and yet subtle vision of the consequences of a Nazi victory in the Second World War, New York as a conquered city within a victorious Third Reich.

Finally, the ever fruitful wells of Jewish visual creativity find what may well be their original source in Ben Schachter’s Eruv Map Project in which a biblical halacha is amended by a visual construct that alters the very definition of Jewish space, the eruv. This artist’s work will be explored in our next review.

Curator Laura Kruger has assembled a remarkable collection of works that all utilize one simple element, a map, to create wildly diverse works of art, many of which redefine our understanding of Jewish life, history and thought. In defining an exhibition with such an unlikely motif, the terribly commonplace map, and yet uncovering such a rich load of creative works, she has yet again shown her dedication to a contemporary Jewish art that is more vibrant than ever, if only one takes the time to look and consider what Jewish artists are creating. Seeing is believing.

Envisioning Maps

Hebrew Union Collage – Jewish Institute of Religion Museum

One West 4th Street, New York, NY