Tzelem: Presence and Likeness in Jewish Art

Jewish Art is a grass-roots movement whose time has come. It has evolved precisely because there are those who are moved by their Jewish heritage and wish to share this experience with the art world, the general public and the Jewish community. There has never been such an exciting time.

Many people see the concept of Jewish art as one of ethnic identity, as a branch of ethnic identity politics. This is true to a point. During the 1960s and 70s, with the emergence of African-American Artists, Gays and the Women’s Movement, it was discovered by these participants that the American assimilationist paradigm of the mid-century was insufficient. In other words there were some people that could not fit in, given their inherent difference from the White Anglo Male majority, despite its cultural assumptions of universality. Jewish Americans, many bent on their own brands of assimilation, took note. Some were in more than one camp. Take for example Judy Chicago; coming from a feminist point of view eventually addressed the Holocaust and her own Jewish identity in her work. A flowering of Jewish American culture followed in part because the limits of assimilation had been set.

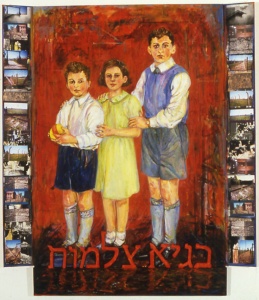

oil on linen canvas, wood and mixed media

But Jewish art is not simply an illustration of ethnic identity. It is also a visual art of no particular style based on Jewish ideas of religion, culture and philosophy. The same period, 1975, is usually dated as the death of High Modernism. The High Priests of New York High Modernism (you should pardon the pun) Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg were both Jewish, although their allegiance to the Jewish community was very conflicted. Rosenberg himself wrote on the possibility of a Jewish art based on a history of Jewish marginality with the mainstream culture. In other words, Judaism with its invisible God, functioning in renunciation of Greco-Roman inspired materialist civilization and its Formalism could in effect create an anti-art. Clement Greenberg’s relationship with Judaism was even more convoluted, even as he proved to be the most influential critic of his generation. His pronouncements of the visual as being separate from all other mental functions, making it in effect holy or sacrosanct and his prioritization of the abstract over the figurative can readily be perceived as a covert re-stating of the second Commandment. “You shall not make for yourself a sculptured image, or any likeness of what is in the heavens above, or the earth below, or the waters under the earth.”

The cultural and social changes wrought by the 1970s and 1980s shifted interest to postmodern discourse. Most of the main players of this movement were Jewish with strong ties to Jewish thought and community. Walter Benjamin, the father of postmodernism, wrestled with Communism and the Kabbalah. His best friend, as is well-documented, was Gershom Scholem, who introduced Kabbalistic ideas into modern Western thought. Emanuel Levinas was a Talmudic scholar; Jacques Derrida was a Sephardic Jew who co-authored a book on religion and referred to himself as Reb Derissa and so on. It is not circumstantial that these men were Jews. Rather their reliance on semiotics, acronyms and Deconstruction reflects a strong Talmudic character as written about by Susan Handleman, Geoffrey Hartman, Steven Schwartzchild, Martin Jay and others.

What does this mean for the average Jewish artist? It has become much more comfortable to espouse hard core Jewish ideas. If Madonna can call herself Miriam and Oprah Winfrey can discuss “The Other” in the context of social action, then these inherently Jewish ideas have reached a mainstream audience as well as transformed the landscape of academia.

If Jews in the field of the visual arts have frankly lagged behind other ethnic groups in espousing cohesion, pride and identification in being Jewish, it should be remembered that we are introducing a difficult concept for the secular art world to accept. We are re-introducing religious ideas onto Modern Art as a possible inspiration, something that has not been readily accepted since the mid 19th century. After all, Romantic and Modern Art were supposed to replace religion entirely. Yet many artists who were not born to religious backgrounds were nonetheless drawn to what Arthur Danto has called “The Jewish Sublime” to be pursued through traditional forms of Jewish study. It is an exciting concept to believe that Jewish religion and spirituality can be extracted from the contemporary assumption that all religious thought is politically conservative, inherently retrograde and worthy of derision or forbidden as a source of creative art. We are in effect changing the rules as to what is aesthetically acceptable. Whether or not this is universally accepted or adopted is beside the point. It is exciting precisely because we are changing the discourse.

The concept of this exhibition, Tzelem: Likeness and Presence in Jewish Art comes from the book of Genesis (1:27). In it, God creates man according to his own image. The words tzelem, demuth and temuna are all used for this concept. The Rabbis, including Rashi, were ever cognizant to keep God transcendent and understood that likeness does not mean simple visual correspondence as it did for the Greeks. What developed was opaque, layered and deeply Jewish. They assumed that likeness equals intelligence and the inherent quality to do good, much like the Creator. While the Greeks postulated a model of Mimesis readily employed in Western Art for 1800 years, Jews tied vision to concepts of moral judgment and the matrix of language, not unlike postmodern thought. One of the reasons that Christian philosophers could marginalize Jewish thought and the Jewish advent into European art during the 19th century was to demean the Jewish links to Linguistic Philosophy. By this, I mean the Jewish system of textual analysis found in Torah, Talmud and Kabbalah known as hermeneutics or exegesis. In the anti-Semitic mind, Jewish thought was not tied to experience at all, just to words. They believed that Jews never built or created anything new or original. See Kalman P. Bland’s excellent book The Artless Jew and Susan Handleman’s The Slayers of Moses.

Often evoked by Jews and non-Jews alike as the Ur source material for Jewish Art, the Second Commandment is restated twice, once in Exodus 20 and again with variations in Deuteronomy 5 and 9. The issue of limiting or destroying all representation is actually a false conundrum here, as the real issue in the text is one of foreign or false worship to other gods. It has always been evident even under the strictest rabbinical conditions that the Second Commandment is determined by context and community and has been applied liberally or conservatively as the community sees fit. It has never been a categorical call, favoring the ear and suppressing the eye as some would have it.

In this regard, the idea of Tzelem presents a Jewish model for vision, one worth exploring in contemporary art. It brings up a myriad of issues regarding the levels of representation or its subsequent renunciation. Jewish thinkers often seek to limit, deform or skew the notion of visual truthfulness, or verism in art. The Code of Jewish Law, The Kitzur Shulhan Aruch does not allow the drawing of a man, especially of a face “unless it is slightly disfigured.” Deforming visual correspondence might superficially suggest abstraction, but in actuality opens the door to all styles and concepts of art, as all discourse is seen as a multivalent language originating within the creator. This language is structured as a prioritized narrative (The Torah) with its subsequent interpretations. Aviva Gottlieb Zornberg writing in Genesis; The Beginning of Desire quotes the Netziv of Volozhin, author of Ha’amek Davar, who translates “to fulfill, to obey” the Torah is to construct the meaning of the words of the Torah. Zornberg concludes that the making of the Torah in the reader’s mind assumes a contemporary understanding of the active process of perception or, to take it further; vision, like reading is a fundamentally interpretive process.

Participating Artists: Ita Aber, Siona Benjamin, Suzanne Benton, John Bradford, Shoshannah Brombacher, Lynda Caspe, Raphael Eisenberg, David Friedman, Tobi Kahn, Rachel Kanter, Tine Kindermann, Robert Kirschbaum, Diana Kurz, Richard McBee, Jill Nathanson, Mark Podwal, Archie Rand, Deborah Rosenthal, Susan Schwalb, Janet Shafner, Joel Silverstein, Adele Shtern, Jack Silberman, Mierle Ukeles, Yona Verwer, David Wander, Menachem Wecker, Laurie Wohl.

In weeks to come we hope to analyze individual works of some of the artists in this truly landmark exhibition.

Joel Silverstein is an artist, critic and teacher and co-curator with Richard McBee of Tzelem: Presence and Likeness in Jewish Art.