Chagall: Love, War and Exile

Groundbreaking and courageous. The current exhibition at the Jewish Museum has tackled what is easily the most vexing subject in the career of the most beloved of Jewish artists; Marc Chagall (1887-1985). Namely: his persistent, indeed obsessive, use of the crucifixion as a symbol of Jewish suffering and persecution. The exhibition, Chagall: Love, War and Exile, under the expert direction of Senior Curator Emerita Susan Tumarkin Goodman, has traced Chagall’s lifelong fascination with the emblem of Christianity, especially in his work created during the Holocaust.

The voice of the artist rings loud and clear as he links his controversial images to specific events: Berlin anti-Semitic riots (1930), Hitler’s takeover (1933), deportation of Polish Jews (October, 1938), Kristallnacht (November 1938), massacre of the Vitebsk Jews (1941), among many other Holocaust horrors. Seen here, his work using the crucifixion dates from the early masterpiece, Calvary (1912, Museum of Modern Art), to late in his career, In Front of the Picture (1971, Fondation Maeght, Saint-Paul de Vence, France). Questions immediately arise: why did Chagall use this potentially painful symbol of the Jews persecutors to symbolize Jewish suffering itself? And more broadly; how successful can appropriation of non-Jewish symbols be used to address specifically Jewish issues?

The fact that the Jewish Museum’s curator Susan Tumarkin Goodman presents these issues as the inescapable core of her exhibition demonstrates the courage to challenge her audience with deeply discomforting images and concepts. As far as I am aware this aspect of his work has never been this extensively examined in a major exhibition. (see my article Chagall and the Cross).

Marc Chagall, educated in Vitebsk’s traditional cheder and well familiar with his family’s Lubavitch beliefs, quickly absorbed the surrounding Russian secular culture, first studying art in St. Petersburg and then blossoming in Paris from 1911 as an archetypal but total unique Modernist artist.

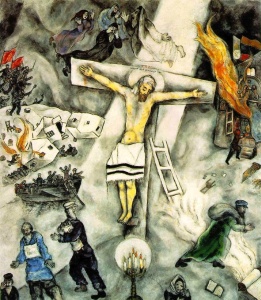

What emerged from this volatile cultural mix was an artist who could easily pursue multiple agendas simultaneously. Russian Jewish shtetl life, Eastern European Christian culture as well as transgressive modernist artistic freedom all came to be his artistic birthright. Significantly, this is exactly what gave him license to appropriate the Christian crucifixion to serve Jewish expression in over one hundred paintings and drawings over his lifetime. “My Christ, as I depict him, is always the type of the Jewish martyr, in pogroms and in our other troubles, and not otherwise” (quoted 1977). Surely this is a highly idiosyncratic and ahistorical approach to an image found in every single Church and Christian dwelling, popularly used to illustrate the responsibility of the Jewish people as a whole for the death of Jesus; the crime of deicide.

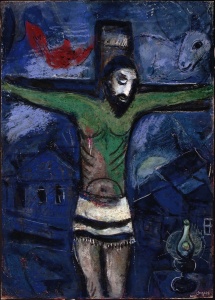

This wanton use of a public symbol for private meanings is frequently a creative disaster, creating a confusion of meanings to a bewildered audience. And while Chagall is not totally immune from these pitfalls, a review of his repeated use of the crucifixion actually yields a more coherent program. By imbuing the image of the crucified with unmistakably Jewish characteristics such as a tallis, tefillin, beard and “Jewish features,” building upon the core fact that Jesus was in fact a Jew, inevitably surrounded by menorahs, rabbis clutching Torahs and the burning shtetl, he goes a long way towards transforming the Christian icon into a Jewish theme.

As the exhibition demonstrates, Chagall has multiple uses for the crucifixion: a personal reflection of himself as the suffering artist, the universal redeemer for Jew and Christian alike, the ultimate symbol of the suffering of the Jewish people under Nazi tyranny, as well as an expression of transgressive modernist freedom. In a very significant manner Marc Chagall is demanding that, if the Modernist revolution indeed freed creativity from the constraints of religious tyranny, academic conformity and soulless art, then a simple Jew from Vitebsk can freely appropriate the consummate Christian symbol for his Jewish ends.

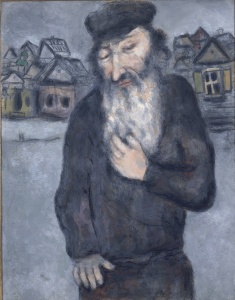

The exhibition unfolds in three clearly defined sections: 1) Chagall’s social, artistic and political roots in the 1920s and early 1930s; 2) Chagall’s war years expressed with the crucifixion and 3) Chagall’s personal tragedy and recovery in exile. In the first section we see his early concern with Jewish life, each group of paintings wonderfully grouped under selective wall texts quoting his poetry that runs throughout the exhibition. Old Man with Beard (1931) competes with Interior of a Synagogue in Safed (1931) and Study for the Revolution (1937) to show the scope of his interests.

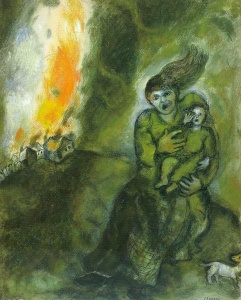

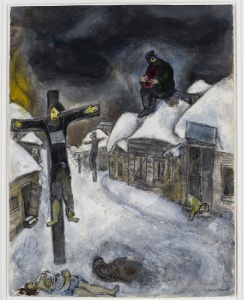

In the middle core section 25 paintings utilize the crucifixion as a major element. The archetypical Calvary (1912) establishes Chagall’s earliest and most hallucinogenic use of the subject to express his artistic and familial trials. Chagall has commented that the figures at the bottom of the cross represent his mother and father. All throughout the 1940’s Chagall’s paintings and drawings search for a balance between the terrifying news reaching him of Jewish suffering and his own increasingly precarious existence in Paris and subsequent exile to New York in June 1941. Fire in the Snow (1942) employs Chagall’s frequently used motif of a fleeing mother and child, here cloaked in green shadows, to fully bring home the horror of losing home, family and community. The Crucified (1944), in response to the battle for Vitebsk, Chagall’s birthplace, brutally confronts the murder of the entire Jewish populace in 1941.

Are we convinced after seeing Chagall’s works that the use of the crucifixion does somehow add to our understanding of the holocaust? For this reviewer, only rarely. White Crucifixion (1938, Art Institute of Chicago, sadly not available for this exhibition), The Crucified (1944) and Christ in the Night (1948) have a calm horror that convinces in a totally unique manner. It is important to remember that when these works were created, Chagall (among many other artists) is actively inventing an aesthetic to talk about the most horrible crime humanity has ever seen. Their search for image and metaphor, let alone comprehensible meaning, continues to be daunting to all who consider this aspect of Jewish experience.

The third section of the exhibition explores Chagall in exile. While the war continued to haunt him, the sudden death of his beloved wife Bella in 1944 plunged him into grief only to be finally relieved by a new relationship and marriage in 1946. These 13 works reflect an artist in recovery from both catastrophic national tragedy and personal loss. The Wedding Candles (1945) is haunting in its poetic vision of a romantic past Chagall never had.

The brilliance of this exhibition lies in presenting us with a Jewish artist who is unflinching in his determination to engage the world in all its beauty and horrors using a visual language uniquely Jewish. As the excellent catalogue essays by Susan Tumarkin Goodman and Kenneth E. Silver explicate, Chagall’s use of the “Jewish crucifixion” arose within ample precedent going back to the 19th century as well as other contemporary artists grappling with the Holocaust and persecution. It is deeply significant that this view of Marc Chagall teaches us that one essential quality of great art is a relentless engagement in the unredeemed world we live in.

From: “For the Slaughtered Artists: 1950”

And as I stand – from my paintings

The painted David descends to me,

Harp in hand. He wants to help me

Weep and recite chapters of Psalms.

After him, our Moses descends.

He says: Don’t fear anyone.

He tells you to lie quietly

Until he again engraves

New tablets for a new world.

Chagall: Love, War and Exile

Jewish Museum

1109 Fifth Avenue & 92nd Street; New York, N.Y. 10128; (212) 423 3200

Saturday – Tuesday, 11am – 5:45pm; Thursday, 11am to 8pm; Friday, 11am to 4 pm.

$12 adults; $10.00 seniors, $7.50 students, under 18 free; Pay What You Wish, Thurs. 5 – 8pm, Free Saturday.

Until February 2, 2014