Contemporary Book Art and Hebrew Texts

The “book” is a mighty big place these days and the current exhibition at MOBIA, As Subject and Object: Contemporary Book Artists Explore Sacred Hebrew Texts is no exception. Highly mobile eBooks compete with online publications and traditionally bound volumes, scrolls, accordion-style tomes and folios that present equally exciting options for contemporary artists to interact with image and text in one unifying medium. The 14 artists shown here take advantage of many of these possibilities to consider distinctly traditional Hebrew texts. The contrast between ancient hallowed texts and cutting edge contemporary mediums is revealing.

As expertly curated by Matthew Baigell, Ph.D; independent scholar & Professor Emeritus: Rutgers University and Adrianne Rubin; Associate Curator/Registrar, MOBIA, the exhibition in MOBIA’s elegant space is divided into two general categories: Subject and Object. In the works that concentrate on “Subject” the emphasis is Inside the Text; utilizing the specific narratives themselves to explore contemporary meanings while those with an “Object” orientation investigate the creative and symbolic possibilities of the physical book in all its manifestations, frequently suppressing the specific text.

Only a handful of these artists are exclusively devoted to bookmaking itself. Most of the others are multidisciplinary artists utilizing “the book” as a medium wherever creatively necessary. Although all the artists have contributed significant works, including: Andi Arnovitz, Lynne Avadenka, Siona Benjamin, Jacob El Hanani, Ellen Frank, Archie Granot, Ellen Holtzblatt, Robert Kirschbaum, Carole P. Kunstadt, Mark Podwal, John Shorb, Robbin Ami Silverberg, Deborah Ugoretz and David Wander, I will comment only on a few to emphasize the contrasting approaches to Book Art presented here.

Professor Baigell’s catalogue essay sets the fundamental tone, stating that “…the artists…works…do not illustrate stories in traditional ways or even insist on specific religious references.” We see this immediately in two epic works by Archie Granot, the Papercut Haggadah (55 pages, 2007) and the Book of Esther (14 pages, 2009). Granot is a master paper cutter, wielding a scalpel instead of scissors to produce the most intricate multi-layered creations imaginable. The text of Book of Esther is richly framed with 14 totally different abstract decorative papercuts, leaving the actual text basically untouched by the riot of design that surrounds it. In sharp contrast the elaborate Papercut Haggadah presents an even richer and varied palette of decoration and invention, frequently invading and subsuming the haggadah text into pure design and removing it from any functional ritual use. Here the “aesthetic values [totally] dominate the textual…”

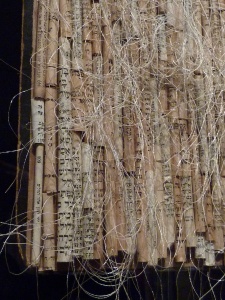

Andi Arnovitz’s three works are even more rarified manipulations of Jewish texts. In two wall hangings; All That is Left and Thoughts Are Precious, Ideas Even More So, she has taken old prayer book pages and leaves from the Gemara, carefully cut into small pieces and rolled and tied with silky threads to be then fashioned into meditations on process and a obscured scholarly memory. Vest of Prayers uses the same raw materials and finally becomes a kind of non-normative ritual object; infused with the holiness of its original sources and yet devoid of an actual Jewish ritual role. They are quintessential art objects parading a deeply pious and yet unintelligible Jewish content, metaphorically reflecting a tragic distance from the real vibrancy of contemporary Jewish prayer and learning.

In yet another aesthetic twist in which the Conceptual and purely Abstract join forces, Robert Kirschbaum’s 42 Letter Name series occupy one entire wall, deftly challenging the viewer to meditate on the multiplicity of one particular form of the Hebrew Name of God. The challenge (explicated in my JP March 25, 2010 review) is simultaneously intellectually abstract and yet rooted in both Jewish mysticism and a three-dimensional model of a nine square cube, deliciously dissected 42 times.

Perhaps at the extreme end of the non-illustrational and ‘arm’s length to text’ spectrum is Robbie Ami Silverberg’s collaborative artist book created in Johannesburg, South Africa. Twenty-two artists contributed images addressing a Zulu creation myth in Emandulo Re-Creation (1997). The pages were divided in half vertically and then cut in thirds horizontally. Bound together so that a viewer could effectively mix and match different aspects of as many as six different artists simultaneously. To further the complexity, a video was made showing exactly these kinds of arbitrary combinations unfolding in time.

Pursuing a radically different approach, the primacy of text and its meaning dominates at least five other works. Siona Benjamin’s Esther Megillah (2010) recasts and thereby returns the Esther story to its Persian roots. Reflecting Benjamin’s Bene Israel roots in Mumbai, India, this illuminated Esther Scroll re-imagines the Esther narrative in a Persian/Indian setting with Esther transformed into a floating blue skinned echo of Vishnu, the Hindu blue skinned Savior, and the wicked Haman as a Bollywood villain, complete with handlebar mustache and outlandish costume. Nonetheless, Benjamin’s vision of the story (reviewed JP March 25, 2011) is no fairy tale, indeed in the climax the Jews are merciless to those who dared to plot their destruction, impaling the decapitated heads of Haman’s sons and riveting their corpses with a barrage of arrows under Mordechai’s firm direction.

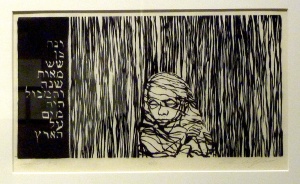

Ellen Holtzblatt hews the primal narrative of destruction and survival in the biblical account of The Flood, “HaMabul,” Genesis 6:11-8:22 with her 14 woodcut prints. They bring a heartfelt urgency to the obliteration of human and animal life that God commanded. The Hebrew text is diversely integrated with close-up images of destruction: dead birds, washed away figures tangled with weeds and detritus that slowly give way to images of hope epitomized by a final panel of a woman with a newborn child, symbolizing God’s mercy in renewal. Missing are images of Noah, his family, the ark and the end of the flood itself; instead the artist notably expresses an intensely personal micro reaction to the first great world catastrophe. Even the passage “And Noah was 600 years old in the days of the flood,” is transformed into an image of a young man beginning to be entangled in the threads of the gathering storm. Her vision of the ancient devastation is visceral.

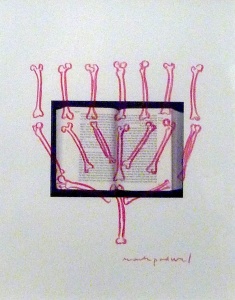

A simpler tack is taken by veteran illustrator Mark Podwal with his concise but encyclopedic Ezekiel’s Vision (2012-2013). His 12 drawings depict 12 prophecies, divided into three registers reflecting 1) Call of the Prophet, 2) The Doom of Jerusalem and 3) Israel Restored. Each image features an iconic image superimposed over a page open to the Hebrew text. In the first Chapter Ezekiel’s vision of the Four Beasts, each of whom had 4 faces, are here represented as the head of a man, a lion, an ox and an eagle mounted on the heads of a 4-pronged letter shin. Surely the shin represents the Divine name, thereby bringing the prophet’s vision an even more holy resonance. The Lord’s question to Ezekiel “Son of man, can these bones live” is seen in a collection of human bones in the shape of a menorah, reflecting the ultimate restoration of the Jewish people both in the miracle of the oil in the time of the Maccabees and the creation of the modern State of Israel, its proud symbol also the Temple Menorah.

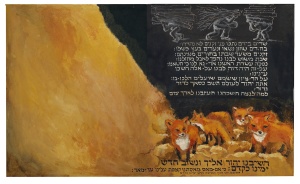

David Wander’s Illuminated Megillah Project, perhaps the ultimate expression of contemporary Jewish Book Art, is represented by the Book of Ruth and the Book of Lamentations (Echah). Both are accordion books measuring approximately 2’ high and 30’ long, here fully displayed. Wander’s narrative of Ruth (reviewed in JP May 10, 2013) is depicted as a contemporary tale with Boaz as a prosperous frum businessman and Ruth as a mysterious young woman searching for her destiny in an urban setting. His Lamentations is radically different, digging deep into the gritty horror of the destruction of the First Jewish Commonwealth. The Hebrew text is written predominately in white on a black and frequently burned background. Relentless images of executions and deprivations lead to vicious birds of prey swooping down as women and children wailing lead to the Temple engulfed in white-hot flames. While it is terribly painful to hear Lamentations on Tisha b’Av, and so too it is the visual experience of Wander’s scroll, in a brilliant way the artist demands hope for the viewer. Dominating the last section is the verse “Bring us back to you, O Lord, and we shall return; renew our days as of old” accompanied by the fateful image of a pack of foxes, echoing Rabbi Akivah’s faithful prophecy (Talmud Makkos 24a) concerning the certainty of rebuilding our beloved Temple.

Whether these contemporary book artists favored technique, material, sacred text and/or interpretation as their emphasis, each pursued in a deeply intimate form of engagement with Hebrew text and tradition, echoing its particular narrative convention by the very serial nature of book art. Book unbound or bound, scroll or fold-out, the dynamic of multiple images to narrate concretely or abstractly defines all these works as reflections of a Biblical narrative paradigm. Clearly that is why we are called the People of the Book.

Contemporary Book Art and Hebrew Texts

Museum of Biblical Art

1865 Broadway (61st Street), New York, N.Y. 10023

www.mobia.org 212 408 1500

Tuesday – Wednesday 10am – 6pm; Thursday 10am – 8pm

Friday – Sunday 10am – 8pm

June 14 – September 29, 2013

Admission Free