Considering Dura: Part III

The significance of the 3rd century Dura Europos synagogue murals paradoxically lies less in their historical importance as the earliest example of Jewish narrative art than in their role as a paradigm of what is possible for contemporary Jewish artists. After all, we have absolutely no other examples of Jewish narrative art on this scale and one might argue Dura is simply an aberration, a curiosity from Late Antiquity, never repeated.

But of course that is its power, revealing the untapped possibilities of Jewish narrative based on Torah, midrash and individual creativity, spanning a gap of 1700 years and, with imagination, finding parallels and inspiration between their world and ours.

Admittedly the images we have are frequently hard to see and, when clear, primitive and foreign. Nonetheless, this unknown artist or artists and the community that commissioned them utilized Torah narratives as a means to comment on the complexity and hopes of their community, a small ethnic minority in a polytheistic Roman border town. The notion of consummate outsiders struggling to forge culture and identity surely resonates with the modern Diaspora Jewish artist.

The Elijah stories unfold as Continuous Narratives on adjacent southern and western walls showing Divine intercession on behalf of the community and the individual. On the southern wall the duel between the unsuccessful Prophets of Baal and Elijah on Mount Carmel is played out (I Kings 18:20-40). Eight Priests of Baal are clad in Roman togas, surrounding an altar with a sacrifice fruitlessly awaiting their god’s fire. Underneath the altar a diminutive figure hides, attacked by a large snake. This is none other than Hiel, evil general of Ahab, who sought to deceptively light the altar fire, only to be eaten alive by a serpent sent by God, as described in Midrash Exodus 15:15. In the next panel Elijah’s sacrifice is being consumed by a conflagration. Elijah appears at least twice, once summoning the heavenly fire on the left and on the right ordering the sacrifice to be drenched in water to magnify the enormity of the miracle. In the struggle against pagan adversaries and corrupt Jewish leadership God can be counted on to come to our aide yet again.

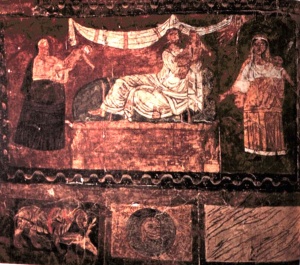

Immediately on the western wall is a depiction of personal salvation, the resuscitation of the widow’s child by Elijah (I Kings 17:10-24). Here the child is seen three times; first lifeless in his mother’s arms on the left, then miraculously alive with Elijah in the massive bed in the center and finally in his mother’s arms, happy and well once again. A prominent “Hand of God” supervises the miracle from above on the right side. The triumphant mood of this panel; a Divine reward for a simple-hearted widow perfectly mirrors Elijah’s triumph over the corrupt but powerless pagan priests who attempt to lead the Jewish people astray.

As an expression of Jewish disenfranchisement in a pagan society it is certainly notable that this first (lowest) register on the western wall presents a theme dominated by women and converts. Already seen to the right of the Torah niche (mentioned in Considering Dura: Part II) is Pharaoh’s daughter, a non-Jew who saves Moses and later converts. So too the widow, a non-Jew from Sidon, nourishes the prophet Elijah and then converts. Not to mention the Jews themselves who witness the miracle on Mount Carmel, effectively converting back to their belief in God. And of course anchoring this entire sequence, the Torah niche with the image of the Akeidah features the singular appearance of Sarah at her son’s sacrifice, witness to the event that arguably caused her death.

Continuing along the first register to the northern wall, are the narratives of Ezekiel. We see the “Hand of God” no less than five times in this long extended panel, practically at eye level, that fleshes out one of Ezekiel’s most explicit messianic prophecies of national redemption (Ezekiel 37). First we see Ezekiel taken by his hair and placed in the valley of the dry bones. Next he is ordered to prophesy to the bones, here seen as disembodied heads, hands and feet; “you will come to life”. The “Hand of God” commands. Immediately a split mountain is seen littered with a toppled house, body parts and corpses, representing a midrash in Pirkei Rabbi Eliezer 33 that states it took a great earthquake to bring the bones to life. The scene shifts next to an earth-red background and we see Ezekiel again, now standing over three figures about to be resurrected upon the arrival of three butterfly-winged angels that are joining one the ground already hard at work.

Another two images of the prophet Ezekiel are seen, now suddenly in anomalous Roman costume. They frame what is the actual subject of the panel, the return of the 10 lost tribes, here as ten men in togas, and the resurrection of the Children of Israel in the time of the Messiah. A singular “Hand of God” of course directs this too. Once we understand the subject and its details, this panel leaps alive in dialogue with the Elijah panels seen on the directly opposite walls. The meaning seems clear; God will resurrect us as a nation and individually in the time to come.

The scholar Jas Elsner (Cultural Resistance and the Visual Image: The Case of Dura Europos: Classical Philology, vol. 96, no. 3, July 2001) has proposed that one fundamental theme to the Dura murals is something called “Cultural Resistance.” With extensive documentation he shows how much of the Dura images present overt criticism of official Roman cult religion and specifically the pagan religious practices found at Dura. The purpose was to push back against a sea of paganism to help preserve Jewish monotheism and strengthen a threatened ethnic identity.

One example of this is found on the second (middle) register of the western wall. Previously I commented in Part I that the big central panels above the Torah niche (labeled Jacob Blessing his Sons) are much too damaged to be really certain of its subject. Nonetheless, the panels are either side present what I would characterize as a Comparative Narrative. If one consults the plan of the Dura murals seen in Part I, the subjects read, from left to right: The Miraculous Well in the Desert, Consecration of the Tabernacle, Temple of Dagon and The Ark Among the Philistines. Many aspects of these panels invite invidious comparison between Jewish worship and pagan practices.

The Miraculous Well mentioned in Numbers 21:16-20 that accompanied the Jews in the desert was in the merit of the righteous Miriam (Taanis 9a). It is seen in the middle of the camp, surrounded by 12 little huts, each with a figure standing in the doorway, hands raised in praise of the life-giving waters being miraculously hosed into each house. Supervising this entire operation is the towering figure of Moses in whose merit the well returned after the death of Miriam (Numbers 20:1). Sharing the central place of honor with the well is the Tabernacle with the golden menorah overseeing the scene. It is a triumphant image demonstrating God’s protection and sustenance for the Children of Israel even after the people bitterly complain against God and Moses at the Waters of Strife (Numbers 20:13) and the incident of the Fiery Serpents (Numbers 21:6). In spite of complaints and punishments our God does not abandon us.

Moving backward in time we see the Consecration of the Tabernacle (Exodus 40:17 and Numbers 7:1) immediately to the right. While here the desert tabernacle looks more like a permanent Temple, the artist is conflating the biblical text concerning the Tabernacle with the relatively recent reality of a permanent Temple (less than 200 years before). The enormous image of Aaron, identified as such in Greek, perhaps for the benefit of non-Jewish visitors, is presiding over the sacrifices on the right and left. The five figures may very well represent his four sons and an Israelite who is also allowed to perform the sacrificial act of slaughter. The “Tabernacle” contains the aron seen in the doorway with the golden menorah prominently placed before it. This obviously schematic representation of the tabernacle conflates symbolically the temporary desert tabernacle with the permanent Temple alluding to the fervently hoped for final Third Temple. This panel celebrates how Jews consistently worship their God, in the distant past, recently and in the future.

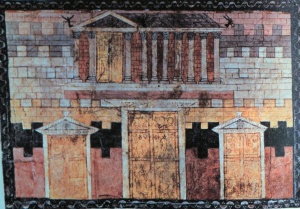

In this Comparative Narrative these two panels, the Miraculous Well and Aaron’s Tabernacle are contrasted with the two scenes represented on the right side of the middle register: The Temple of Dagon and the Ark Among the Philistines. The triumphant message could not be clearer. The next image is a grim study in closed doors and rigid hierarchy. The temple is flat, schematic and generic; unlike any other scene at Dura no human being is depicted in this panel. It is identified as non-Jewish by the pagan images on the central door, recognized as well-known Roman gods. There is no life or religiosity possible in this wasteland. Next is the image of the Ark of the Covenant captured in the Temple of Dagon. In the Philistine sanctuary their cultic idols are smashed and the Philistines are rushing to expel the Ark from their midst. This God of the Hebrews is much too hot to handle. Theologically it is a scene of devastation, a pagan apocalypse. For the Dura Jews the message could not be clearer, the pagans don’t have a chance.

Dura Europos has a lot to teach us. As artists and appreciators of art the mix of three different narrative styles; Symbolic, Continuous Narrative and Comparative Narrative presents a wonderfully complex assortment of tools to search for and find meaning. This is compounded by the liberating structure of multiple textual sources; the Bible and the midrash commentaries to interact with the artists own point of view. The freedom to actually add the presence of God in the form of “The Hand of God” seems to create the notion that almost anything is possible in this creative environment. Add in an assortment of different costumes, figures seen in different scale and perspective motifs and we end up with a kind of visual cornucopia that feels increasingly post-Modern in its eclecticism.

Indeed, Dura stands as the earliest example of Jewish narrative art; perhaps only now, so many years later, ready to take its place as the rich foundation upon which a complex, creative Jewish narrative art will grow in the years to come.

Looking at Dura we are on the cusp of the future.

N.B. I am deeply indebted to many of the scholars referenced in this review, especially Gabrielle Sed-Rajna’s work Ancient Jewish Art (1985) Chartwell Books, NJ and the images found therein.