Considering Dura: Part I

The dilemma of the Jewish artist is that he or she is often dismissed out of hand as a cultural and halachic impossibility. And yet a very real history exists to reveal a great many antecedents. Jews have made Jewish art for at least two thousand years; 20th & 19th century paintings, five hundred years of making ritual objects and illustrated prayer books, haggadahs, megillas and ketubos not to mention the extensive production of illuminated manuscripts between 1300 and 1500.

And in the Land of Israel at least 18 decorative mosaic synagogue floors spanning the 4th through 6th centuries of the Common Era have been uncover so far. Where did it all begin? The answer is simple: Dura Europos.

“Aladen’s Lamp had been rubbed and suddenly from the dry, brown, bare desert had appeared paintings, not just one nor a panel nor a wall but a whole building of scene after scene, all drawn from the Old Testament in ways never dreamed of before”; exclaimed Clark Hopkins, one of the first archeologists to see the newly discovered frescoes from the synagogue at Dura Europos in 1932.

In that one exciting location there are no less than 14 major narratives depicted on the walls of the synagogue. They are not symbolic ciphers, rather they are fleshed out scenes that evoke in a complex and often midrashic style well known Torah narratives. They had been painted for this synagogue sometime around 245 CE in the frontier Roman town of Dura. The town was overrun and destroyed by the Persians in 256 CE and forgotten until the British accidentally uncovered it in 1920.

PART I

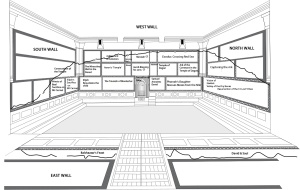

The Dura Europos murals are enormously important in the history of Jewish art, displaying an “iconographical language that is a fully developed narrative art that has no antecedents…” (Gabrielle Sed-Rajna) Three types of narrative art arranged in three levels or registers on the three surviving walls at Dura can be outlined as follows:

1) Symbolic / Narrative; the Messiah & Jacob Blessing his sons framed by; Moses at the Bush, Moses ascending Mount Sinai (?), Abraham and the Covenant (?), Joshua (?), and the Akeidah over the Torah niche and the anointing of David,

2) Sequential Narrative (or conflated narrative); in the panels of Exodus, Finding Moses, Elijah on Mount Carmel, Elijah Resuscitates the Widow’s Child, Triumph of Mordechai, Ezekiel and the Valley of the Dry Bones.

3) Comparative Narratives; The Well sustains the Camp in the Wilderness, Consecration of the Tabernacle (?) as opposed to the Temple of Dagon (?) and the Ark in the Temple of Dagon.

While a number of the identifications are subject to scholarly debate and no mutually agreed overall narrative program has been agreed upon after close to 80 years of study and debate, there is a consensus that the panels are obviously not chronological, nor simply illustrational. There are simply too many idiosyncratic and/or midrashic visual elements to read the images literally. Most scholars maintain there is some underlying ideological and didactic program.

Some of the opinions of the narrative program include R. Mesnil du Buisson (1939), discerns historical, liturgical and didactical themes corresponding to the three primary wall registers; A. Grabar (1941), sees the frescos as a running commentary on official Roman art; R, Wischnitzer (1948), interprets the images as expressing a hopeful messianic theme; Erwin R. Goodenough (1953): perceives Dura as a non-rabbinic mystical cult; Carl Kraeling (1956) sees expressions of heterodox beliefs, ignoring normative injunctions against images; J. Gutmann (1972), posits the celebration of the new liturgy that substituted for the Temple sacrifices; Gabrielle Sed-Rajna (1995) reads the hope of collective redemption in affirmation of the covenant and Jas Elsner (2001) sees in the frescos an aggressive commentary on the surrounding pagan religions. This is just a sampling of scholarly opinion concerning the meaning of the Dura frescos.

This wide body of informed conjecture on the painting’s meanings amply highlights the rich diversity of subjects the Jewish community at Dura chose. For our purposes a simple description of the primary narratives will help orient us to this difficult but inspiring masterpiece of Jewish Art.

The western wall is the most complete with at least 12 large narrative panels visible. In the center is the Torah niche surmounted by the large panels of subjects that may represent Jacob Blessing his Sons and the Messiah (according to Goodenough). Clearly an important central image, it is simply too damaged due to numerous repaintings to comment on intelligently. This central panel is framed by four standing male figures each clad in a Greek (i.e. Roman) robe (chiton) with a cloak (himaton) draped over it and sandals. Their poses are typical of Eastern Roman Art of late antiquity; fully facing the viewer, weight of the body on one foot in profile, the other foot slightly forward. They all sport short Greek-style beards. One clearly represents Moses at the Burning Bush while the others may represent Moses ascending the mountain, Abraham at the Covenant and Joshua with a Torah scroll.

The Torah niche though is quite clear in its symbolic representation. A stylized Temple and closed aron secures the center with Temple Menorah and a lulav and esrog on the left. This became a typical depiction of the much yearned for Third Temple in synagogue representations for the next 300 years. While in many similar depictions a shofar is seen, here it is replaced in the right section with the Binding of Isaac. The ram is tied to a small tree at the bottom while Abraham stands at the ready with a large knife. Isaac is atop the altar while a heavenly hand stops the sacrifice. As far as I am concerned, the non-textual insertion of a tent with a figure standing in the doorway in the upper right represents Sarah’s apprehension and reaction to what almost happened to her only son. Sed-Rajna comments that “This scene is the first attempt in Jewish art to transpose a literary account into visual form. […] marking the transition between symbolical language and narrative art, the first among the countless images of the sacrifice, basic to Jewish iconography…”

The importance of these images cannot be overstated. As one of the earliest sections of the Dura paintings it is also the prototype for all Jewish synagogue decoration for at least the next 300 years. Secondly it boldly substitutes a pictorial narrative (the Akeidah) for a symbol (the shofar), brazenly thrusting Jewish religious expression into the visual realm, utilizing the means of the surrounding culture to concretize our faith and claims on God’s mercy. The fact that these images also integrates Sarah’s role in the Akeidah is all the more startling since in subsequent representations she is almost never depicted.

So if indeed this is “beginning of Jewish Art” some pointed questions must be asked. Considering the complexity of images and sophistication of organization of the entire cycle, all the scholars believe that this artwork must have had antecedents. What were the models? Could there have been a Jewish tradition of manuscript illumination, now totally lost, that depicted similar narrative cycles? Or does the style of the paintings derive form the extensive visual traditions of surrounding pagan cultures, Roman, Persian and Syrian? The longer we study the Dura Synagogue murals the deeper the mystery becomes. In Part II we will continue our exploration of the narratives so tantalizingly presented at Dura Europos.

N.B. I am deeply indebted to many of the scholars referenced in this review, especially Gabrielle Sed-Rajna’s work Ancient Jewish Art (1985) Chartwell Books, NJ and the images found therein.

1 Comments

Amah Jones

Wow! It’s nice to finally see accurate depictions of ancient Hebrews—from Moses the African, Abraham with his Kushite ancestors, Jacob and just about anyone worth mentioning as black people. Moses leading the Hebrews from Egypt, crossing the Red Sea, with the Pharaoh’s army in pursuit? That’s powerful. Both the Egyptians and Hebrews are accurately presented as black people. Let’s hope the images don’t get altered or whitewashed in the future. It has been a great eye opener in biblical anthropology.