At Home in Florence?

The auction at Christie’s in Paris this May 11 of a Tuscan Mahzor, created and illuminated in the 1490s, will be an extraordinary event. This rare example of illuminated Jewish art has never before been seen publicly in over 500 years and, aside from tantalizing internal suggestions, is lacking conclusive identification of the scribe and illuminators.Because the gold-tooled goatskin binding was made about 50 years after the manuscript and has a different coat of arms than those found in the mahzor, it is assumed that this prayerbook may have quickly changed hands. Aside from the 17th century censor’s notations, all that is known is that the manuscript was sold sometime before 1908 in Frankfort and then noted in Elkan Nathan Adler’s important Jewish Travellers in 1930. One thing that is certain is that from both the style and content of the illuminations the Jewish family who commissioned it were very comfortable in Renaissance Florence where they probably lived. Or were they?

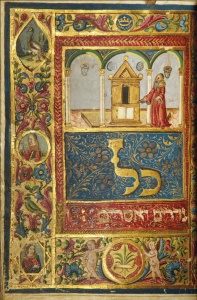

The style of the frontispiece and the following 68 of 422 folios (pages front and back) are said to be characteristic of the noted Christian illuminator Boccardino il vecchio (1460-1529). His patrons included the Medici, rulers of Florence at the time, and he was noted as a master miniaturist by Giorgio Vasari in Lives of the Artists. For a Florentine Jewish family to employ an artist of such renown is not surprising since the community was very close to the Medici family, so much so that Lorenzo il Magnifico (1449-1492), whose humanistic agenda supported Jewish scholarship, was considered a protector.

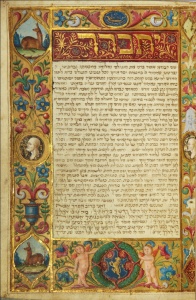

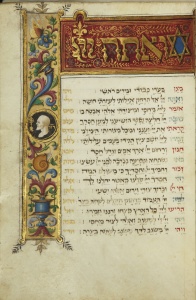

The frontispiece, “Yis’barach,” apparently the beginning a compilation of verses, is notable for the delicate floral decoration framing medallions of animals in landscapes and cameo heads. In another of the eight pages that feature significant decoration (including 4 full page illuminations), a liturgical poem is framed by a similar motif of floral decorations typical of Florentine Renaissance manuscripts. One can make out a snail creeping up the foliage as well as a delicate butterfly at the top of the left border. The portrait cameo features a noble profile with an armillary sphere and the name Dovid in Hebrew on the right. The armillary sphere was model of celestial objects orbiting the earth and was frequently used as a symbol of knowledge and wisdom that probably referred to the manuscript’s first owner, possibly named David. The equally elaborate initial word panel, “V’atah Hashem,” in gold leaf against a deep red ground, features an unusual Magen Dovid that may also allude to the first owner’s name. Additionally the fleur de lys above the name of God seems to refer to the city-state of Florence itself, notably identified by fleur de lys with the unique spikes between its pedals.

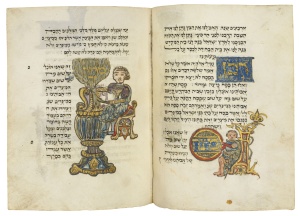

Kay Sutton, Christie’s Director of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts and Ilana Tahan, head of the British Library’s Hebrew collections have examined this manuscript and feel that the illuminations after 68v were done by followers or the workshop of Boccardino. Additionally some images may actually be from an untrained Jewish hand, most notably the page in the Haggadah section depicting Matzah and Maror. It is clear the scribe left space for illustrations and all three works here exhibit an inexperienced hand distinct from the sophisticated images on the earlier pages. Both “matzah zoh” and “maror zeh” feature seated figures literally presenting the item at hand. The man with the maror is completely out of scale with the object that the maror is resting on. Both the chairs and the stand feature prominent Magen Davids at their base and the fantastical chair also sports a fleur de lys at its top.

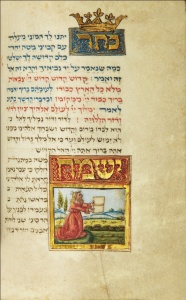

The page featuring the Kedushah for Shabbos Shemoneh Esrei is typical of the more refined illuminations; the image of a crown (Kingship is a typical Sephardic designation of this section) announces that we effectively crown Hashem with the words of the Kedushah. The word panel “Moses rejoiced” is a charming image of a blond Moses, rays of light emanating from his head, kneeling and wearing a sumptuous red robe as he receives two tablets from the unseen Divine Presence in the upper right corner. Set in a pristine landscape the entire scene radiates optimism and joy that beautifully reflects the emotions expressed in this Shabbos prayer.

In these images almost certainly done by non-Jewish artists the imagery can present iconographical problems. The fully illuminated Kol Nidarim page (notice the Italian “Minhag bnei Roma” Hebrew version of the prayer) introducing the Yom Kippur evening service is bordered by two medallions with stock Renaissance portraits, two classical nude putti presenting a roundel with a seven-branched plant and finally one medallion with a peacock. The intended meanings, if any, are not clear. Above the gold leaf word panel “Kol” is an image of a scarlet robed individual, without tallis, head uncovered, pointing to the open Aron displaying an open, but blank, book. The idea in general is understood but without the specifics of a Jewish service.

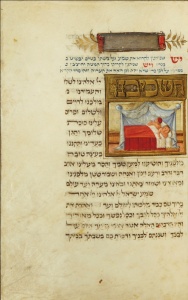

In its way the illuminated initial word “Hashkiveinu” (Lay us down to sleep) is clearer and more to the point. The homebound prayer of the bedtime Shema is here illustrated with a scene in a canopied bed. The husband is on the far side of the bed, his red kippah identifying him as he faces towards the rear wall ostensibly saying the bedtime Shema. His wife is seen on the near side of the bed, holding the covers up over her body and facing us with a startled and concerned expression. Piety and modesty in action.

Perhaps another cross-cultural expression is to be found in the full-page illumination of “Order of Rosh Chodesh and Blessing the Moon.” The scene is set with a Renaissance nobleman, alone and elegantly dressed with cape and hands lifted in an approximation of prayer. He gazes piously, again bare headed, at the moon and the stars in a paradoxically daytime scene. The crescent moon is filled in by a face of a smiling ”man in the moon.” The religiosity shown in this simple image is but an approximation of Jewish ritual since both the rites of Rosh Chodesh and Blessing the Moon are notably done in the presence of a minyan.

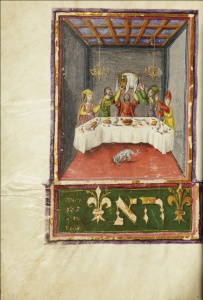

On the more familial level the Passover Seder is notably illustrated by a depiction of lifting the Seder plate during the recitation of Ha Lachma Anya; “This is the bread of our affliction…” The table is laden with various loaves, implements and foods. What is being raised though is not an actual plate but rather a basket, a white cloth covering what appears to be various kinds of fruit. In the prominent foreground is a white dog gnawing on a bone. Much seems to have been lost in the translation.

This manuscript presents many intriguing questions. Because many of the later illuminations evidence other artists and even non-expert hands, is this an example of a commission in which funding simply ran out and was patched together as best as possible in succeeding generations? Perhaps more importantly, do the conceptual disconnects between the textual ritual and some of the illuminations, point to a failure of communication between the non-Jewish artist and the patron? Perhaps most importantly, was the Jewish patron satisfied with the final product? Was the comfort level perhaps more of an illusion on the Jewish side than the reality of the Renaissance Christian/humanist consciousness? Much further study is needed to uncover some of this manuscript’s mysteries.

It should be noted that while I only had 20 minutes to examine the Christie’s Mahzor while it was in New York, the preliminary scholarship of Kay Sutton of Christie’s and Ilana Tahan of the British Library provided an invaluable foundation for many of my observations. I believe that this Mahzor provides a complex and fascinating example of Jewish / Gentile relations in Renaissance Italy and sincerely hope that the next owner will provide ample opportunity for future scholarly study.

Christie’s Paris

Auction: Importants Livres Anciens, Livres d’Artistes et Manuscrits

9 avenue Matignon

75008 Paris, France