At The Jewish Museum: Charlotte Salomon’s Legacy

What would do if you knew there was a play, a play with text and music, that told the story of one whole life. A Jewish life. The story of a young woman, told from before she was was born until her life was about to be taken away by the cruel horror of the Holocaust. Now I warn you, this is a life you might not approve of. Would you be curious?

This woman, Charlotte Salomon had none of the trappings of a traditional Jewish life. But she did have all the accoutrements of the assimilated German Jews in the early twentieth century.

Highly educated, cultured and sensitive, her family was plagued by suicide, family problems and depression. Her father was a surgeon and her step-mother a professional singer. But most importantly, she was a wonderful artist. She took her life and made it a work of art. Would you take the time to peek into a life that now can only speak to us from the ashes?

What this 26 year old has left us is a monumental work of art called Life? or Theater? currently on exhibition at the Jewish Museum. It is comprised of almost 800 gouache (opaque watercolor) paintings. The selection of 400 paintings shown here are masterfully inventive visual images that sometimes combine text and even musical cues referring to popular tunes and classical music. It is totally based on her life and family and yet told as a fictional biography of a certain Charlotte Kann. Since all of the characters of her own life are remade here into fictional counterparts it allows her to tell her story with a curious distance and yet absolutely unnerving intimacy.

This series of paintings is structured like a play with a prologue, main section and epilogue divided into scenes and sections. The prologue begins with the suicide of her maternal aunt (her namesake), her parent’s courtship, her own birth and infancy. It continues in one of the most harrowing (not horrific mind you) passages that re-imagines her mother’s suicide.

She lovingly relates her bedtime story in which her mother yearns for the life of an angel that inhabits the celestial spheres. The young eight year old Charlotte is fascinated by the fantasy of her mother’s story. She makes her mother promise to send her a letter from heaven describing the celestial realms. Every picture transports us into the childlike fantasy of this memory and re-understanding of the past. Charlotte only found out the real cause of her mother’s death years later. At the time it was hidden from her and Charlotte awaited patiently the letter from heaven. The combination of simple text narrated in the third person and constantly inventive paintings make this passage riveting. She has invented that which she never witnessed and confronts what which she cannot avoid; for anyone the most painful of memories. Would you be able to step inside her shoes, if only for an hour, and gaze at her paintings?

Loss and the struggle to carry on; the fact that we are swept up by events imposed upon us by our loved ones and then buffeted by social and political changes beyond our control are all the subjects of this far reaching and complex work of art. The prelude continues with Charlotte’s life in Weimer and Nazi Berlin. Her father remarries. We are witnesses to this new relationship developing with her stepmother, Paula, a highly regarded contralto. The introduction of her stepmother’s voice teacher, “Amadeus Daberlohn,” and his important artistic and personal role in her life is what consumes the main section of this play.

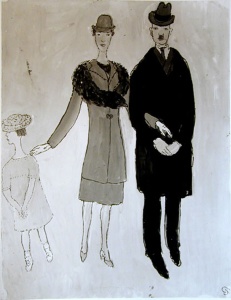

Charlotte Solomon uses every conceivable pictorial device to propel her narrative forward. Sometimes she creates multiple frames, like a storyboard for a motion picture, advancing scene by scene. The earlier painting are detailed evocations of a distant childhood, recreated in rich color, multiple details and “primitive” overviews combining many scenes in one picture. Sometimes she adopts an aerial perspective, peering into multiple rooms of the family house with the ceilings cutaway. At other times her vision is in classic primitive style, different narrative events stacked one on another, three, four and five registers, all making up a complex story. Occasionally she reverts to simple expressionist line drawings that simply depict her family or a cherished portrait. She was trained in the State Art Academy in Berlin from 1936 to 1938 but was forced to leave because she was a Jew. Would you be thrilled by the masterful diversity of color, technique and style she summons to tell us her life?

After Kristallnacht in 1939 Charlotte’s father and step-mother sent her to the south of France for safety. Her exile is depicted in the play’s epilogue. It at began optimistically, bright colors, the beach and the warmth of her grandparents home. But soon both family tragedy and the encroaching war close in on her again. Sometime late in 1940 she begins work on her massive play Life? or Theater? working alone for at least two years to complete the 800 gouaches. The final section is much sparer in execution, with more text intruding on the images, almost feverish in haste as if she knew time was running out. In 1943 she meets and marries an Austrian-Jewish refugee. They are discovered and both deported to Auschwitz. Before being deported she gives her play to a local resistance doctor, telling him “take good care of it; it is my whole life.” At Auschwitz she is murdered. Isn’t this what art is supposed to do, to transport us into the thoughts, visions and conceptions of the artist? Can we feel, hope and cry through the artist’s mastery? Charlotte Solomon takes us through her life until its end. She speaks to us still and we need to listen.

Charlotte Salomon: Life? Or Theater?

Until March 25, 2001

Jewish Museum

1109 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y.