Chagall and The Cross

The oft-repeated quote by art critic Robert Hughes that Marc Chagall (1887-1985) was the “quintessential Jewish artist of the twentieth century” perhaps reveals more than the normally mordant writer intended. Chagall’s role as celebrator of a dream-like vision of the Russian shtetl sharply contrasts with his personal rejection of Judaism and the norms of traditional Jewish life. This contradiction encapsulates one particularly poignant aspect of modern Jewish artistic experience. When Jewish artists assimilate they lose a precious perspective and often forget who they really are. The current exhibition Chagall and the Bible at the Museum of Jewish Art and History in Paris purports to explain how Chagall, famously known as a ground-breaking modernist and charming creator of folk inspired lovers, flowers and mythological fantasies, is also a serious 20th century Biblical artist. That of course is not difficult considering the vast amount of biblical work he produced. However, curator Laurence Sigal and deputy curator Juliette Braillon additionally wish to reconcile Chagall’s considerable Jewish inspired work with his disturbing tendency to include overt Christian images in biblical and Jewish subjects. In attempting to explain the recurring image of the crucifixion in his later work they have confronted one of the most disturbing elements in Chagall’s entire output.

The exhibition, expertly hung and presented, is composed of three thematic sections: Chagall as an “Illustrator of the Bible” is exemplified by his massive graphic work of 105 plates, The Bible (1931-39, 1952-56) including many early color studies and later versions and editions. This body of work conclusively establishes Chagall’s status as a modern biblical artist and is so rich that it deserves a totally separate analytical review. Secondly, “On the Path of his Ancestors” briefly explores his work done in Palestine in the 1930s. This serves as an introduction to Chagall as an “Interpreter of the Bible” and, more broadly, Jewish life and conditions. It is here that we see the vast majority of his Christian images. Finally “The Bible Illuminated” gives us Chagall’s preparatory drawings for four stained glass projects he designed; one for Hadassah Hospital Chapel in Israel and the others for churches in Switzerland and Germany. This last section seems to propose that Chagall’s mastery of the biblical transcended his parochial Jewish identity, lest we get the impression that Chagall was only a Jewish artist.

Not surprisingly, angels are a bit of an obsession with Chagall. For an artist consumed by the fantastic constantly invading the everyday fabric of life, early images of flying lovers, fiddlers dancing on rooftops and grandfather clocks sailing through the air are quite the norm. However Chagall takes the role of the angel a step further, depicting on a number of occasions the artist himself as a heavenly being with wings. Angel with a Palette (1927-1936) is but one of many expressions of the artist as a kind of divine prophet. Without doubt Chagall took his role in society as a serious visionary; responsible to comment and when necessary, alert the world to the dangers it was drifting into during the perilous interwar years.

One salient feature of Chagall’s working method was to continue to work on some artworks over a number of years. Considering his enormous and consistent productivity throughout his career, it is not unfair to attribute this kind of artistic rethinking and reworking as a kind of unease and struggle with certain difficult subjects. Considering the dates of Fallen Angel (1927-1934-1947), I believe it represents Chagall’s struggle with the deterioration of European politics and subsequent war and holocaust. As a shtetl Jew flees to the left with an open Torah scroll, a vivid red angel plummets earthward, upside down and aghast at its fate. In this darkly pessimistic painting the left side is populated with symbols of Chagall’s youthful work; a yellow cow, a violin, a flying man and grandfather clock. On the right, just past the red angel, is a lone candle alongside a crucified Jew, his tallis loincloth clearly visible in the dark shadows. A mother and child appear in one of the angel’s wings. By the time the painting was finished in 1947 the fate of Europe’s Jews was well known. His painterly message of the fallen angel denotes the failure of art, and indeed the artist, to avert the tragedy. The icon of the crucified has become the symbol of the murdered millions.

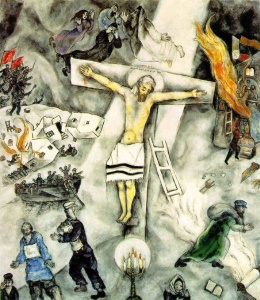

Chagall had used the crucifixion as a symbol of Jewish suffering in the preceding decade, most particularly in the White Crucifixion (1938), Art Institute of Chicago and not in the Paris exhibition. It was painted right around the same time as Kristallnacht, November 9, 1938. Others, notably radical Yiddish poet Uri-Tzvi Grinberg (Greenberg), had earlier used this Christian symbol as representative of the oppression of the Jews in Europe. Grinberg immigrated to Palestine in 1924, had early on predicted the Holocaust, and once in Palestine, fought in the Irgun and Lehi and served in the Knesset in Begin’s Herut movement. It is almost certain Chagall knew his early poetry utilizing the crucifixion. This use of the crucifixion as a symbol of Jewish suffering and victimhood is an understandable appropriation of a time-honored European symbol. Its use by Chagall, according to the wall text, was to “appeal to Christian consciences by equating the martyrdom of Jesus with the suffering of the Jewish people.” The underlying problem with this approach was that centuries of Christian anti-Semitism had nullified whatever there was left of the “Christian conscience.” Unfortunately Chagall’s assimilation to secular French culture had effectively blinded him to that reality.

Chagall continued to grapple with the immense tragedy of the Holocaust and frequently used the crucifixion as a symbol in his works, but now more and more in a radically different role. As he sought answers in his role of artistic prophet he now utilized the crucifixion as a kind of universal symbol, “attempting to reconcile mankind whose foundations had been shaken to the core by the Holocaust.” Chagall pursued a vision of a humanity united under the imagined dual inspiration of Judaism and Christianity.

Crossing the Red Sea (1955) is one of the large Biblical paintings he painted between 1955 and 1973 that subsequently became the core of the Museum of the Biblical Message (National Museum Marc Chagall) in Nice. It is one of the most powerful paintings here and yet one of the most troubling. This visionary work is a meditation between a poetic white angel leading the Jews through the sea and a yellow-robed Moses commanding the sea to drown the Egyptians. The evocatively powerful primary colors sets the majestic drama; Egyptians a flurry of red desperation, the sea an ethereal blue and the angel a heavenly white. While the Jews are mere ciphers they merge beautifully with the graceful angel who seems to effortlessly dance at the head of the Exodus. Slowly secondary themes emerge. A diminutive angel brandishes the Ten Commandments to the drowning Egyptians while up at the top of the painting two images in the dark sky frame the saving angel. On the left King David is seen playing his harp, softly pointing to the historical glory of the Jewish people. Yet on the right there is the crucified Jesus, acting as a perverse beacon to an alternative Jewish future.

![Yellow Crucifixion [detail] (1943) oil on canvas by Marc Chagall Courtesy Pompidou Center, Paris Yellow Crucifixion [detail] (1943) oil on canvas by Marc Chagall Courtesy Pompidou Center, Paris](https://richardmcbee.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/yellow_crucifixionchagall-225x300.jpg)

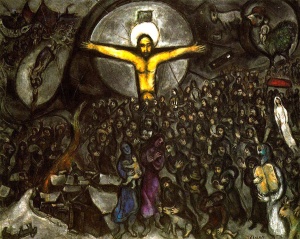

In Yellow Crucifixion (1942-43) we see a canvas dominated by an open Torah scroll presented by a shofar-blowing angel alongside a gigantic crucifixion of a Jew wearing tefillin and crowned with a glowing halo. This is no victim; rather he is presented as some kind of answer to the suffering below. In an even more dramatic image, Exodus (1952-66), the seminal event of Jewish history, is presented with hundreds of shtetl Jews streaming forward, led by Moses carrying the Ten Commandments on the lower right. The scene is presided over by a towering yellow crucifixion, literally embracing the mass of colorless Jews. Perhaps as no other painting seen in this exhibition, this image reveals the raw visual power of the Christian crucifixion symbol that ultimately could not be overcome by Chagall’s artistic mastery.

At the end of the exhibition the wall text asserts “Marc Chagall was probably the only Jewish artist of his generation to confront another religious tradition without ever betraying his own… he forged a universal message.” Sadly this is the tragic flaw in many of Chagall’s crucifixion paintings. In the final analysis, there is no universal message in Chagall. Rather there is his misunderstanding of the crucial distinction between the Oneness of Judaism and the illusion of secular universalism. Judaism proclaims that only God is one. It is precisely that Oneness that creates critical distinctions between God and His created, between His nation and the nations, between Torah and illusion. Chagall’s universalism exploits the universalistic dogma inherent in the dominant Christian culture to pretend significant distinctions don’t exist between people and ideas. In his struggle to understand our terrible century, Chagall did not betray his religious tradition; he simply forgot it.