The Eruv in Contemporary Jewish Art

For most observant Jews, the eruv is invisible. Each week we prepare for Shabbos: ready our food, conclude our mundane affairs, shower, dress and put the house keys in our pocket and check the web that the local eruv is up. Unless there has been a storm or other physical disaster, we can assume everything is okay. Just like the Shabbos calm that descends for 25 hours, the eruv operates for us in the background: essential but unnoticed.

At Yale that is not the case. Margaret Olin, senior research scholar at the Yale Divinity School, has curated a groundbreaking three-part exhibition that critically examines this three thousand year old fundamental rabbinic institution, the eruv. As far as I am aware the intricacies of a complex halacha such as the eruv has never been subject to an artistic investigation, not to mention an entire exhibition of eleven diverse artists. Interestingly almost all of these artists are not observant and that may be exactly why they can feel free to artistically engage in this forbidding subject.

Mel Alexenberg, venerable conceptual artist, teacher and writer, has paradoxically one of the more traditional works in this show, a digital print on canvas, The Miami Beach Eruv (1998) that reflects its initially “hidden” nature. We see a gaudy Art Deco façade on Ocean Drive (Miami Beach) that brandishes the glory of the material workaday world. Meanwhile a black and white digitalized image of Rembrandts’ fleeing angel (Angel Leaving Tobias, Louvre) is caught in this morass, symbolizing the religious Jew trapped in Miami’s culture of flesh and sensuality. And yet the thin eruv line stretches across the top, reminding us of Shabbos and delineating the permissible from the forbidden.

In a more practical vein Margaret Olin, the show’s curator and conceptual creator, presents us with a photographic primer on the very nature of the eruv. Her 35 photographs (2010-2012) and illuminating texts (including Maimonides, Talmud Yerushalmi, Franz Kafka, Michael Chabon: The Yiddish Policeman’s Union) present the purpose and means of the urban eruv. Describing it as “This Token Partnership” wherein multiple private dwellings agree to share a common space and its ownership by means of shared food (such as a box of matza), Olin begins her images simply with the matzah of the Yale eruv. The scope of course quickly expands to include whole neighborhoods “shared” by means of symbolic walls and doorways, constructed by the most minimal of means, defined by her as “urban bricolage.” This term, amazingly appropriate for the eruv, is a postmodern technique in music, visual art and architecture in which ordinary and/or found objects are combined to create artworks. In the eruv this of course includes the sides of buildings, fences, telephone poles, wires and anything else that can be halachically patched together to create the legitimate borders of a shared private space. Her examination of the New Haven/Yale eruv with its rabbinic supervisors exposed the physical and conceptual complexities of such a project and guided her photographs of the Manhattan, New Haven, Chicago and Jerusalem eruvim, all of which are represented here. By focusing on the intricacies of the necessary vertical posts (lechi) and the horizontal posts or wires (koreh elyon) either in beautifully abstract close-ups or the seemingly invisible halachic borders in disarmingly simple street scenes, the viewer is slowly brought into the complex mindset of rabbinic urban architecture.

Olin’s images explore how the urban eruv simultaneously includes and excludes city spaces with her image New York Hilton marking the Sixth Avenue border of the Manhattan eruv, paradoxically shutting off access to Jews who carry on Shabbos. Similarly she also explores eruv wires in Israel, such as the one in Abu Tur running past an Islamic institution, that proudly wave their “flags” and make the weekly checking easier. In America “flags” tend to be more discreet; except where on the Lower East Side a pair of sneakers works just fine as an indigenous “flag.”

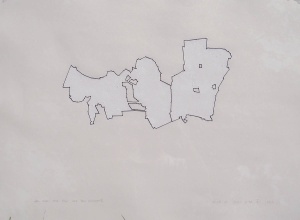

Another aspect of the first section of the exhibition is an exploration of theoretical concepts that the eruv summons. Ben Schachter’s Eruv Maps (reviewed here) are naturally in abundance in this exhibition. These twelve deeply conceptual works slyly reproduce the map outlines of city eruvim using simple thread as the border, thereby echoing the wire that creates most actual eruv borders. These works operate by collapsing the vast physical size and complexity of the eruv, seen in Olin’s images, into simple artworks, each 20” x 30”. In some aspects these works make the eruv project more comprehensible, indeed, graspable. By doing so his work unexpectedly points out just how abstract and creative this rabbinic innovation actually is. As the catalogue notes, his eruv maps are “emulations of emulations,” reflecting the reality that “the eruv emulates architecture through a summary drawing in space by means of fishing lines and wires, so he emulates that drawing through his own fiber art…” It is the parsing the borders of interior / exterior (and at times interior exclusions or ‘holes’), real and imagined structures and walls, Shabbos boundaries and weekday spaces that make the eruv such an intriguing concept.

Ellen Rothenberg “explores modes of thinking in space” by strikingly printing over 20 quotations concerning the eruv by the Rambam on a 15’ curtain suspended from a wire strung wall to wall. As if the Rambam’s partial statements were not puzzling enough, they are printed vertically so that to see them one must twist one’s head sideways. Rothenberg’s strategy is to physically engage the viewer in the ideas she finds intriguing. Similarly, her photos of a black line drawn from her elbow to her fingertip (the length of an amah) and across two clenched fists (2 tefachim) impose rabbinic measures into the reality of the artist’s physicality, and by extension the viewer’s.

While Suzanne Silver’s Kafka in Space sees the eruv as a “semiotic code” in relation to a Kafka quote she believes refers to the rabbinic fence, her installation of possible eruv parts and a neon sign that boldly announces “eruv” in Hebrew and English, is less than convincing, requiring a strenuous leap of faith by the viewer. Initially Elliott Malkin’s installation, Modern Orthodox, prompted a similar reaction. After all, how could his laser-beam eruv, on display in the courtyard just outside the gallery and recorded by a video monitor inside, be considered a serious and substantial “wire” that delineated a Shabbos boundary. However, upon reflection, how could the rabbinic constructs of a mere wire and portion of an upright post be considered a “doorway” as part of a “wall” to change the halachic status of a semi-public space into a fully protected private space to allow carrying on Shabbos? Could a laser beam provide as much a halachic warning as a practically invisible string? Perhaps. But more importantly we understand that the primary function of art is to raise questions, not provide answers and Malkin’s work does exactly that as he addresses the rabbinic eruv’s fragile and ephemeral nature.

The exhibition continues in the gallery at the Joseph Slifka Center for Jewish Life at Yale with the work of three photographers who consider the eruv in Israel. Alan Cohen sees the eruv as embedded in the architecture of Ultra Orthodoxy, specifically in the cityscape of Me’ah Shearim, Jerusalem. In almost all his images the Jerusalem stone of the ancient houses provides a timeless backdrop for the artificially white eruv lines in remarkable contrast to the black and grey of the banal utility wires. It is almost as if the eruv’s sanctity has bleached the wires with purity.

In contrast to Cohen’s wires Daniel Bauer ponders the eruv poles as he finds them in the Israeli landscape. They seem to confront the countryside and open fields as an aggressive imposition, pushing back against the landscape. In his elegantly composed Untitled (Pine Trees) a lone eruv pole is centered in fledging grove of pine trees planted on the side of a hill. This Shabbos border marker seems to fit right in with the trees until we notice directly behind it a poured concrete construction site just up the hill. One wonders if the pine trees have a fighting chance as they are encroached upon by Shabbos on one side and urban sprawl on the other. Here the eruv become symbolic of Israeli’s relentless development and residential expansion.

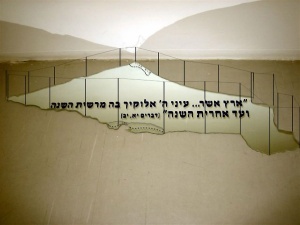

Finally Avner Bar Hama considers the larger borders of the land of Israel. His Eruv Tahumin: Gush Katif (2005) ponders the tragedy of the expulsion of this Jewish community through an image of its former external border. The ruin of a guard post lies just inside the eruv/security-light poles perimeter. Seen from the inside, the lights face outward over the sand dunes to the sea beyond and evoke a deep sense of loss and desolation. Mutual-Responsibility of the Country (2006) considers Israel from afar, the entire Israeli map outlined with stylized eruv poles demarking the land from the rest of the world. In the middle of the image is the verse “A Land that…the eyes of Hashem, your God, are always upon it, from the beginning of the year to year’s end” (Deuteronomy 11:12).

The exhibition concludes in the galleries of the Yale School of Art, one of the foremost art schools in the nation, and shows a profoundly generative artwork on the eruv. The artist, Sofie Calle, is not Jewish and is an international art celebrity, known for her controversial works that are “sleuth-like explorations of human relationships.” The Eruv of Jerusalem (1996, beautifully designed installation by Eduardo Vivanco and the curator) consists of 20 starkly vertical photographs of eruv poles, delineating the edges of Jerusalem’s Shabbos permissibility; each identical and yet in a different location. Alone, these are the authoritative images of boundaries that surround the holy city. And yet in this exhibition they surround a table that tells another story. The table in the middle is a map of Jerusalem with the eruv clearly delineated in red, punctuated with 14 small photos that tell quite a different host of private stories. Here the photo locations reflect 14 vignettes about private episodes and meanings that are contained within the strict confines of the eruv. Each, culled from personal interviews Calle randomly conducted, is deeply personal and linked to very specific places that are randomly found within the Jerusalem eruv. Arab and Jew, religious and secular, Calle denotes that lives deeply imbued with meaning, loss, love and joy occur within this magical wall of the Jerusalem Eruv. Her installation considers a border of consciousness containing and celebrating the importance of a geographical place and human memory.

Finally a double projection video, Turbulent, by Shirin Neshat goes beyond the confines of the eruv and explores a relationship between a male performer and a female performer mediated by the poetry of the 13th century Persian poet Rumi. It too depends on borders and the reality that separates audience, performer and art.

This brilliant exhibition has explored a vast range of meanings that arise out of the eruv; from its practical reality, impact on concepts of borders, transformation of urban and rural space, local and national, to a social consciousness that affects Jew and non-Jew alike. Remarkably these artists have plumbed the complexities of a deeply Jewish subject by seriously considering a rabbinic construct that for most of them was foreign. Significantly this surrender to Judaic ideas is the hallmark of a truly radical contemporary Jewish Art.