The Medieval Haggadah: Art, Narrative & Religious Imagination By Marc Michael Epstein, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2011

The Dura Europos synagogue murals (245 CE) evidenced the first great flowering of Jewish visual creativity, quickly followed by the creation of at least 17 synagogue mosaic floors in Palestine. The next efflorescence of Jewish art was found in illuminated manuscript production in Spain and Germany over 600 years later.

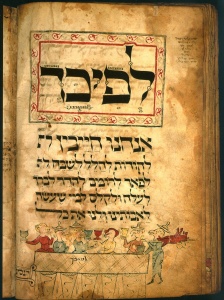

In The Medieval Haggadah: Art, Narrative & Religious Imagination (2011) Marc Michael Epstein explores four seminal medieval Haggadot as paradigms of the creative relationship between sacred text and the Jewish visual imagination. The four medieval Haggadot: the Bird’s Head Haggadah (Ashkenazi ca. 1300), the Golden Haggadah (Sephardi ca. 1320), the Ryland’s Haggadah (Sephardi ca.1340) and its “Brother” Ryland’s Haggadah (Sephardi ca.1340), are created at “a crucial historical moment for the development of Jewish visual culture…[that] developed a renewed interest in narrative painting coterminous with the emergence of Christian narrative art.” Here I shall consider only his analysis of the mysterious Bird’s Head Haggadah (Israel Museum, Jerusalem MS 180/57), the earliest illuminated Haggadah we have, because it sets the fundamental tone and context for his research and conclusions. In future reviews, I hope to address his fascinating exploration of these other medieval Haggadot.

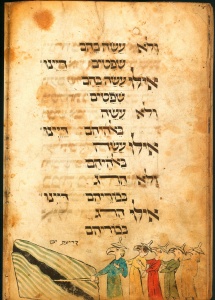

Epstein brilliantly deconstructs many assumptions and visual preconceptions we (and many earlier scholars) frequently bring to these medieval Haggadot in an analysis that returns us to their original social and religious contexts. He does this by insisting that we see the illuminations as an independent commentary to be understood in parallel with the Haggadah text, not subservient to it. Of course one of the greatest initial challenges he faces with the Bird’s Head Haggadah is the substitution of bird’s heads for almost all of the human heads in the manuscript. While other manuscripts around the turn of the 14th century, both Christian and Jewish, utilized this same motif, the vastly different contexts thwart a single understanding for all, and certainly not as a universal Jewish method of satisfying a halachic injunction against image making. Nonetheless here the visual affront is particularly difficult for modern eyes. Depicting Jews with bird’s heads is simply grotesque.

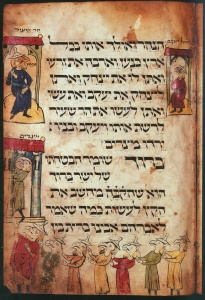

Many scholars see the use of bird’s heads in this southern German manuscript as indeed a negative pietistic concession to rabbinic censorship of Jewish image making. Only the Jews are depicted with bird’s heads while the non-Jewish faces (Pharaoh, angels, etc.) are depicted with no faces at all (any non-Jewish faces were later additions). Epstein identifies three halachic authorities in this region that provide the background for these distortions. Judah the Pious (1140-1217) is considered the founder of Chassidei Ashkenaz and strictly prohibited any image making. R. Meir of Rothenberg (1215-1293) disapproved of the practice as being a distraction from the text. Finally R. Ephraim of Ratisbon (Regensburg 1133-1200) prohibited only the human face but permitted depiction of animals and birds. In this context Epstein sees our Haggadah as a liberal approach to the issue of making human images. But then he notes that actually the heads depicted are composite creatures with many of the heads sporting strange mammalian ears! His conclusion is that what we have here is an extremely typical medieval composite creature found in many illuminated manuscripts: the griffin, a combination of the lion and an eagle. Naturally for Jews the composite creature of a lion (lion of Judah) and an eagle (on whose wings we escaped Egypt) would be a perfect choice. The griffin has an extensive iconography as a creature of honor and pride, Jewishly echoing the lions and eagles woven on the curtain on the Holy of Holies, those found on the divine Chariot of Ezekiel and even linked to the Cruvim on the Ark of the Covenant. Far from a negative self-image, the griffin headed figures in this Haggadah are celebrations of Jewish identity, especially in contrast to the non-Jewish figures who literally have no substantive identity. The suitability of the griffin for the Jew’s heads in this manuscript, thought to have been created in the southern German city of Mainz, is further established by the text of a kinah for Tisha b’Av (Kinos; Rosenfeld, pg 133) by Kalonymus ben Judah (11th c. Mainz) that mourns the destruction caused by the first crusade (1096); “For the noble ones of the esteemed congregation of Mainz who were swifter that eagles and stronger than lions.” Epstein’s analysis is breathtaking and convincing. The figures in the Bird’s Head Haggadah will never seem the same.

A similarly incisive analysis is extended to the Judenhut or Jew’s hat that is worn by only some of the bird-head Jews. By means of internal comparisons Epstein proves that the hat, only enforced as a punitive identifier of Jews later in the mid to late 14th century, was here used to signify adult males of substance and piety, i.e. superlatively Jewish! Therefore both the bird’s heads and Jew’s hat are positive, normative symbols of proud Jewish identity, contrary to much received scholarship and our initial impression.

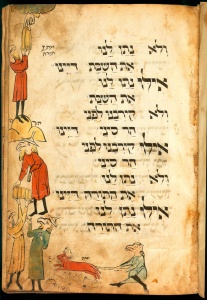

One notable exception to this motif of depiction is the figure of Joseph seen in Egypt as Jacob and his sons are entering. Joseph has indeed a bird head like all the other Jews, but he is lacking the honorable Judenhut. Epstein reads this seeming contradiction as evidence of the illumination being in tension with the normative rabbinic view of Joseph as the paradigmatic righteous Jew. One defining factor of Jewish life at the time was the problematic phenomenon of certain Jews’ close relationship to the local rulers, precursors to the later Court Jews. This is of course the narrative truth of Joseph’s role in Egypt. He seemed so Egyptian in dress and speech that his brothers did not recognize him as a Jew at all. And indeed in a telling critical gesture the artist denied Joseph a Judenhut. As Epstein explains, “it is necessary to understand iconography as exegesis: commentary on the way scripture was read through the rabbinic lens, offered from the perspective of medieval experience.”

In many aspects of his analysis Epstein links the specifics of the illuminations, their exact placement alongside the Haggadah text and the choice of certain episodes over others as a running commentary on tensions and conditions of the contemporary Jews of Mainz in the 14th century, both internally and in relation to the surrounding Christian culture.

Considering the fact that “in medieval Jewish visual culture there were few if any iconographic conventions,” the Jewish artist was forced to utilize the “common iconography of the period and place.” Therefore Epstein provocatively states, “the central program of medieval Jewish visual culture was radical reinterpretation” necessitating a “revolutionary and creative exegetical enterprise in and of itself, the tools of which were cutting, pasting and juxtaposition.” This concept casts Jewish art of the medieval period and, perhaps almost all periods, into a radically different and subversive light. It transforms the well-worn trope that generally Jews either do not possess or have only a weak visual culture into a complex and powerful tool to both create a vibrant Jewish visual art and simultaneously comment on our relations with the surrounding civilization.

While with the selective use and interpretation of symbols Epstein locates one level of meaning, his analysis of “clusters” of subjects reveals the narrative sequence as a more expansive meaning source. Specifically he “believes the arrangement of the illustrations represents the singular genius of its particular authorships.”

In tracing three narrative clusters as they appear in the unfolding Haggadah text and additionally an interweaving of the Passover sacrifice and home observance, Epstein finds potent parallels to medieval Jewish life and concerns. The initial depiction of Esav opposite Jacob establishes “a parallel with or a response to Christian images of Ecclesia and Synagoga,” a persistent tension for 14th century Jews elaborated at the bottom of the same page with Jacob and his sons entering Egypt and, one page away, depiction of beardless, hatless Jewish slave labor building Pithom and Ramses; surely “images of displacement or alienation” all too familiar to medieval Jewry.

Next to the phrase, “We cried out to Hashem” Moses and Aaron are depicted praying to the Divine Presence as a blue cloud, in stark contrast to the text’s reference to the cries of Jewish slave labor. Epstein feels that this disjuncture indicates that the figures actually refer to Psalm 99:6-8 “Moses and Aaron… would call to the Lord and he would answer them…” At the bottom of this page we see the Akeidah stopped just in time under the words “and God remembered His covenant with Abraham, with Isaac and with Jacob.” Medieval Ashkenazi Jews, “reinterpreted the Akeidah narrative as a mirror of their own communal martyrdom, so fresh in their communal memory.” The artist therefore sees Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice that “becomes the basis of a [literal] covenant between God and Israel.” Guided by Epstein’s analysis, it is important to note that in this narrative cluster, the illuminations are specifically NOT illustrating the Haggadah text. Rather they are offering a supercommentary that presents a deeply contemporary parallel visual ‘text.’

While I have only touched on a few of Epstein’s insights, one salient fact needs to be elucidated. Almost all of the underlying assumptions concerning the Bird’s Head Haggadah are scholarly educated guesses. We have no factual or documentary proof of either date or location or community of creation of this Haggadah, only stylistic comparisons and learned deductions. Now of course that is not at all unusual in research about many medieval manuscripts. But what is especially dramatic about Epstein’s analysis is the courage of his scholarly conclusions. His erudition in terms of that which we do know, i.e. biblical, Talmudic and legal texts along with surviving historical records, is truly staggering. But he consistently pursues his arguments further in giving voice to the independent meanings of the images themselves. Hand in hand with his scholarship is an artist’s eye for visual narration and meaning. And by doing this he liberates his work from being a simple historical analysis.

Epstein’s methodology provides a paradigm for contemporary Jewish art. By lauding a medieval Haggadah for its integration of text, tradition, visual exegesis and contemporary meaning, he has shown it to be a model for 21st century contemporary Jewish art to be subversive, interpret “against the grain” and engage in our vast Jewish subject matter with courage and insight we never thought possible.