Bible Scenes

“And the Lord prepared a great fish to swallow up Jonah.” Rabbi Tarphon said: That fish was specially appointed from the six days of creation to swallow up Jonah… He entered its mouth just as a man enters the great synagogue, and he stood. The two eyes of the fish were like windows of glass giving light to Jonah” (Pirkei d’Rabbi Eliezer 10).

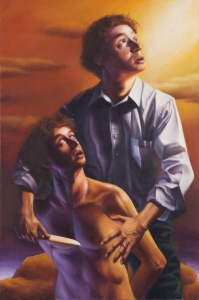

The first splash must have been overwhelming, punching the breath out of Jonah’s lungs and plunging his soul into terror for its very life. Being swallowed whole Jonah reaches out for salvation as he is consumed by, according to the midrash, the ultimate place of sanctity, a fish created by God for this one purpose to shock him into teshuva. It was like entering a synagogue, a living holy of holies, so sacred that one freezes, only able to stand in awe and fright. This is what Simon Carr’s painting Jonah and the Whale (2005) conveys to us. The stately biblical narrative has been transformed into a bodily experience that allows us to finally imagine its spiritual dimension. Jonah twists in a hopeless struggle to remain in his former rebellious domain, the material world of flesh and blood, water and air. Carr’s painting is the painful moment of revelation for the reluctant prophet.

This painting is featured in a fascinating exhibition Scenes from the Bible at the Synagogue for the Arts in Tribeca. The exhibition features 28 paintings and relief sculptures exclusively dealing with Biblical subjects in a diverse array of styles ranging from the primitive work of Malka Zeldis and John Servetas to the highly stylized pop rendition of the Golden Calf by Ora Lerman. John Bradford, reviewed in these pages many times, weighs in with a Moses and Pharaoh and The Golden Calf while Jack Silberman presents delicately poetic watercolors from Isaiah, David and the Ark and a pastoral Akeida.

The curator, Lynda Caspe, has 3 bronze reliefs that are fascinated with biblical violence. Abraham and Isaac captures the “Do not stretch your hand against the lad…” moment, father shielding his son’s face with a protective hand even as the other hand bears the knife of slaughter. Her episodic The Story of Cain and Able narrates the myriad details of that tragic tale while a much smaller Cain and Able reduces the violence into one horrific act. Cain is standing, his raised arm about to plunge a knife into the back of a terrified Able who is desperately clinging to his brother for mercy. A primeval mugging.

Another kind of violence, perhaps psychological but equally disturbing, is found in two large paintings of illustrator and painter, David Wander. His 13 large ink drawings, The Jonah Drawings, were reviewed here. These works, both from 1989, are startling contemporary visions that slowly reveal their complex meanings.

Akeida presents in dramatic contemporary terms the moment the angel summons Abraham to stop. Wander’s approach is deeply personal, unwilling to distinguish between biblical narrative and present-day drama. The clean shaven Abraham is wearing a white shirt and dark trousers. A wedding ring on his left hand is yet another unmistakable modern touch that immediately brings to mind the violence this act does to his marriage with Sarah. These details notwithstanding, it is the astonishing similarity of the faces of Abraham and Isaac that stops the viewer in their tracks. It is taken of course from a Gemara in Baba Mezia 87a that relates at the weaning of Isaac the guests scoffed: “‘Granted that Sarah could give birth at the age of ninety, [yet] could Abraham beget at the age of a hundred?’ Immediately the lineaments of Isaac’s face changed and became like Abraham’s, whereupon they all cried out, Abraham begat Isaac.” Seeing this notion represented is unusual enough but in this context it crystallizes another important concept of the Akeidah, i.e. that of the unity between father and son at this crucial moment. “And Abraham said, ‘God will see the lamb for Himself for the offering, my son.’ And the two of them went together” (Genesis 22:8). Rashi comments “even though Isaac understood that he was going to be slaughtered… they went together with an equal heart.” In the Wander painting both Abraham and Isaac are startled by the unwelcome interruption in the sacrificial ritual. Isaac stares up at his father, practically imploring him “What are you waiting for?” while Abraham seems to be dumbfounded by the brilliant light of the angel’s command. The dramatic realism of father and son’s perfect faith and obedience is deeply unsettling.

Another kind of violent interruption is the theme of Wander’s other painting, Lot’s Wife. Similarly set as a contemporary event, Mrs. Lot is clad in a simple dress seen in profile as she twists around in horror to see the burning Sodom, here represented as a simple country house engulfed in flames. Her hands are frozen in fright predicting her imminent fate of being turned into a pillar of salt, immobile and lifeless for all eternity. The shocked expression on her face, perhaps even eliciting a gasp of horror, probes into the narrative in a far more disturbing manner than the traditional notion that she was simply punished for disobedience and past evil inhospitality. Wander condenses the notion of an entire city burning into a single house aflame to drive home the point that what Mrs. Lot saw and understood was her entire universe being destroyed, her whole world being represented by her home. Suddenly Mrs. Lot is transformed from a stock biblical transgressor into a living breathing modern tragedy, inexplicably punished for an emotion and reaction we can all too well understand.

The Pirkei d’Rabbi Eliezar 25 elaborates that the angels said to Lot and his family; “Do not look behind you, for verily the Shekhinah of the Holy One, blessed be He, has descended in order to rain upon Sodom and upon Gomorrah brimstone and fire. The pity of Edith, the wife of Lot, was stirred for her daughters, who were married in Sodom, and she looked back behind her to see if they were coming after her or not. And she saw behind her the Shekhinah and she became a pillar of salt…” Now the Wander painting becomes even more poignant as we understand her irresistible need to see, her motherly instincts searching for her daughters no matter how evil. And of course no one can see the holy destructive power of the Shekhinah and survive. That is exactly the tragedy that Wander shows us.