The Power of Ritual Objects: 92 Years of Judaica at Bezalel

When one lights that very special menorah or breathes deeply near a hand-crafted besomiah at havdalah, one releases the “power of the ritual object and [confronts] the questions it raises.” Such Judaica is the “intersection of belief and art,” a veritable cornucopia of meanings and esthetic delights. Such is the experience at 92 Years of Judaica at Bezalel, Continuity and Change, currently at the Yeshiva University Museum as expressed by the curator, Muli Ben Sasson.

This splendid selection of over one hundred objects of Judaica, ranges from a choice selection of objects from the Old Bezalel school that emphasizes a nationalistic art that “sought to awaken the slumbering spirit of the ancient Prophets of Israel” to contemporary Judaic artworks that are a fusion of the New Bezalel, inspired by Bauhaus internationalist design and a renewed interest in Jewish ritual objects. The question is, exactly how does this supposed power of the ritual object manifest itself and what meanings are brought forth from such simple ritual items?

Design. That was the great innovation that the New Bezalel, via the modernist Bauhaus aesthetic, contributed to the late-twentieth century appreciation of Judaica. The modernist concept of “design” stipulates that the very shape and functionality of something, in conjunction with a heightened awareness of the materials used, can be a powerful tool to create new meaning from a functional object.

One example of this is the Torah Crown created by Arie Ofir in 1996. It is composed of a multitude of silver spikes seeming to dance on a silver base atop the Torah. Above that is a triad of inverted silver, copper and brass pyramids that float over this forest of wavy spikes. These three shiny but empty vessels are enigmatic, suggestively open to the heavens that might capture the Divine flow. Perhaps they are vessels to capture the words of Torah, Ketuvim and Nevim. This work transforms a Torah crown into a receptor of heavenly transmissions.

Further on in the exhibition, this artist focuses on a much more mundane mitzvah with his design of a hand washing cup. Considering the banality of the use of the object it is amazing what Ofir does with it. He has designed a vessel, silver on the outside and copper inside, with the handles inside the container. Now, by grasping through the circular hole in the center of this tubular flask, you suddenly realize you are surrounded by that the substance that can purify you; we simply need to activate it and pour it out on our hands to begin the ritual process. His creative design forces us to rethink the simplest of mitzvahs, washing our hands.

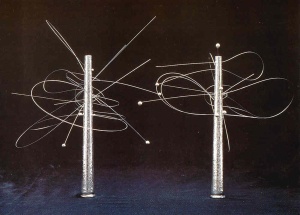

In contrast, the rimonim of David Palterer are anything but mundane. These works from 1997 are tapered silver shafts that extend the wooden eitz haiim to become the focus of a fantastic silver wire universe. The silver dots of planetary projectiles seem to be caught in orbital suspension, suggesting vast distances of spiritual freedom emanating from the holy Torah. In another exploration of the format of rimonim, the Yemini family offers a generational tour de force spanning over fifty years. In one case we can see Yehieh Yemini’s silver rimonim from 1940, delicate and traditional. Next to him is his son’s, Yaacov Yemini, rimonim, dated to 1960. They stand proudly as a boisterous pair of triplet open globes, each housing a precious golden bell to ring out the announcement that the Torah has arrived. Finally, Boaz, the grandson, exhibits a bold return to the traditional pomegranate form with his postmodern and evocative design for silver Torah finials.

This beautifully designed exhibition is based on a number of intertwining concepts. One is that the development of Judaic objects can be found in certain “Family Stories” as illustrated above. Secondly, the motif of teacher and student evolutions is explored in various works. Finally we discover another undercurrent in some of the works known as the Rosenthal Project. This is a conscious attempt to link individual Judaic creations by Bezalel students with the process of international production. In 1996 a cooperative project was launched between the Rosenthal Factory in Germany and the Bezalel Department of Ceramics and Glass Design. The idea was for the students to design objects, such as besamim, hanukiot and dreidels for commercial production. The results shown in the exhibition are objects of clean design, frequently cast ceramic or porcelain, and surprising subtlety.

While claiming to be a historical survey of the Judaic production of the Bezalel School, this exhibition is actually an exploration of different trends in Judaica in the last twenty years. The exhibition was originally created in Jerusalem as a collaboration between the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design and the Jerusalem Fairs and Conventions Bureau, a major source of contemporary Judaica. This has been a very fruitful partnership exploring the best of the rarified world of artistic creation and the fine craft marketplace.

A unique approach to Shabbos candlesticks is seen in Ofer Rachamin’s brass 1985 work. First of all the lights are firmly linked by a simple arc of brass, denoting their absolute unity. But then the artist undermines that concept by creating two oil vessels that are balanced opposite from one another, swinging out in differing arcs that are held in place by a common steel thread. This means that whoever makes the brocho over these lights must self-consciously bring them together mentally, grappling with the rebellious disunity of the everyday world to create the conceptual unity of Shabbos.

A similar transformative effect is felt in the 1998 Spice Box for Havdalah by Malka Kohavi. This witty design, blends the functionality of a stem pierced with dozens of holes and the pop humor of the totally artificial rose, to elevate our spirits and tickle our funny bone simultaneously.

The power of the Judaica in this exhibition cannot be conveyed by photographs. Like all sculptural works, they must be seen from multiple angles, walked around and their reflections savored visually. This experience points to the power of ritual objects to transform our experience as we interact and perform mitzvoth with them. Indeed, as the excellent catalogue states it, the individual Judaic object can only hope to “transmit a message” as the artist strives to be “bezal-el,” one who merely stands in the “shadow of God.” This exhibition shows just how successfully that can be done.

Published in The Jewish Press