Archie Rand – Jewish Enough

This is it. This is the one exhibition that you must see if contemporary Jewish Art matters at all. Archie Rand has been bravely creating radical Jewish art for at the last twenty years, challenging both the contemporary art establishment and the purveyors of Jewish culture. As a consequence of this insolence he has been exiled to what amounts to a critical wilderness. It is time to redeem him from exile, time for the Jewish public to take note and acknowledge the accomplishments of the foremost creator of Jewish art working today. Our cultural future depends upon it.

Yeshiva University Museum is to be commended for its courage in showing this selection of works from the 1990s that begins to give an idea as to what Rand is all about. The diversity and scope shown here is simply breathtaking, and informative. Rand insists that “If you invest everything in one specific effect, one wonderful drawing, one conclusive image, you are worshiping false gods,” and therefore he draws from many sources, working in a series as part of his strategy against the constant lure of modern idolatry. A dyed-in-the-wool postmodernist, he is deeply engaged in process, uninterested in producing the “great masterpiece.” The one constant in his work is an insistence on Jewish subject matter. Nonetheless the multiple meanings and unanswered questions his works provoke are his “religious identity, bound up in the unfinished painting, expressing humility before God.”

Psalm 68 (1994) consists of thirty-six paintings, each encompassing a block of English text encased in an abstract representation. Deliberately choosing a difficult text, thirty-six verses long and complex, Rand challenges the viewer, “would you want this text on your living room wall?” He defiantly answers that if the content is Jewish, he can make art with it whether it is inherently appealing or not.

Rand’s long and contentious history of engagement with the Jewish community has led to a heady kind of freedom to choose his subjects and formats at will, insisting that he creates for an as yet undefined audience that accepts only one elemental proposition; “they must feel Jewish.” More and more today that audience is ready and ripe for connection, but that wasn’t always the case. At the B’nai Yosef Synagogue in Brooklyn, his first major Jewish mural project in 1974, he immediately encountered heated opposition to his use of images in the Sephardic sanctuary. The halachic dispute was resolved finally by the intervention of the revered Rabbi Moshe Feinstein but the tension persists between the artist and a prevailing suspicion of the visual arts on the part of religious Jews. While he feels unfairly criticized by the religious, the secular cultural elite is even more damning. His consistent use of Jewish subject matter, especially religious narratives, has earned him excision and scorn from the art establishment. Curiously though, it has liberated him.

Gods Change, Prayers Are Here To Stay (2000) presents what at first looks like a visualization of Yehuda Amichai’s beautifully iconoclastic poem on God, prayer and Jewish life. Rand has arbitrarily placed over parts of the primitive images a portion of the first line of each stanza. The truncated text intrudes on the impastoed surface, refusing to visually integrate thereby violating expected aesthetic conventions. Reading the full poem only heightens the disjuncture as one realizes that the images do not illustrate the words. Therein lies the genius of these twenty-four paintings. Each image is a commentary and an elaboration of the text.

Whoever Put on a Tallis graces an image of a rampant lion, the symbol of a confident Judaism found on many proud Torah arks. The complete meaning emerges as one reads the rest of the line “when he was young will never forget.” The poem speaks of the comfort of the tallis, “snuggling into it like the cocoon of a butterfly…” Rand expands the text to speak of the pride and comfort of Jewish ritual. Once examined each one of these panels explodes the surface meaning and, utilizing fragments of poetry, creates ironies, accusations and celebrations.

Rand’s strategy of flouting artistic conventions, his willful, awkward and frequently unaesthetic images are a reflection of deeply held belief. “I am engaged in a life and death struggle, what do I care if a specific red ‘works’ or not!” He refuses to choose between an abstract or figurative idiom, maintaining that “after abstract expressionism fell apart all visual languages became co-existent.” His Nachmanides Letter to his Son (1993) attempts to penetrate in thirty-one abstract images the simple message of the Ramban to his son to banish anger, accept humility and stand in constant awe of God. The Hebrew original and an English translation is subtly embedded in the bottom of each image, creating a kind of illuminated book spread out over the wall for quiet meditation.

In 1989 the Jewish Museum included his fifty-four Parsha Paintings in the controversial exhibition Too Jewish. Norman Kleeblatt wrote that they “merged quotations from limited Jewish iconographic sources with those from… Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism and Pop… adding fake jewels to the corners of the canvases… [thereby to] reverse… the high seriousness of the abstract masters whom he appropriates.” Rand now sees these works as a turning point in his imagery. He feels he has moved beyond respectful midrashic illustration into total appropriation of other mediums to communicate his frequently subversive meanings. Instead of attempting to create a new Jewish iconography he is now intent on “allowing it to emerge out of the creation of the paintings.” Contemporary Jewish art will find its form not in history but in process.

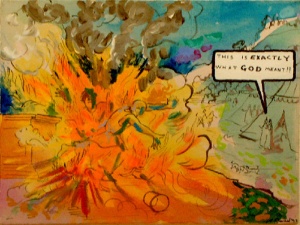

Sixty Paintings from the Bible (1992) utilizes a contemporary technique, the comic book, embedded in one of the oldest forms of Jewish representation. These images are taken from a set of seventeenth century engravings, Icones Biblicae (1630) by the Christian artist Matthaeus Merian. Rand’s appropriations, common in Jewish art throughout the ages, are similar to those of the widely reproduced Amsterdam Haggadah of 1695. The difference here is that Rand uses the images as a mere scaffolding to “reassess the Tanach, get past the standard English translation and find the ‘punch’ of the original Hebrew.” The comic book technique (invented and dominated by Jewish artists) now becomes the means to facilitate Archie’s translation. His use of the word balloon, bold letters, underlining and italics, allows him to simultaneously emphasize text and image and comment on both. The Sacrifice of Isaac presents an angel interrupting Abraham about to slaughter his son. Abraham looks up exclaiming “I’M HERE!” This response, textually true and yet visually impatient and impertinent, implies a fundamental challenge to God’s concept of a test.

Further Rand insists on working on all sixty paintings at once, breaking into the traditional forms with garish Pop color and arbitrary areas of completion and sketchiness. What emerges from the cultural clash between Baroque drawing, Pop painting and cartoon blurbs is a far reaching reappreciation of the Torah text. Rand’s cultural layering exposes what was always hinted at in Jewish art, that cultural forms do not necessarily contain immutable meanings, that in fact culture is permeable and adaptable to creative appropriation. This approach is deeply Talmudic, asserting that there is little in the world that cannot render service to Heaven.

The Sons of Aaron depicts the moment Nadab and Abihu are consumed by a Heavenly fire for bringing “alien fire” before Hashem. Hot colors depict the violent event while the background is sketched in thin washes. Unexpectedly Rand’s word balloon erupts from one of two background figures, presumably Moses, exclaiming, “This is EXACTLY what GOD meant!” Hosts of commentators have puzzled over the meaning of the death of Aaron’s righteous sons. Rand’s ironic text headlines that God’s purpose is anything but exactly clear.

This kind of liberating realization that our Jewish texts are expansive, that Jewish artists are not limited to the piety of stock explanations or the wearisome proclamations of Jewish identity, this is what makes Archie Rand’s work vital. His work challenges us to devour our literature, our history and lives and make art, make meanings and begin to construct a Jewish culture. This exhibition shows an artist whose work is not “Too Jewish” but finally Jewish Enough.