A Call to Art from the Torah World

“We have inherited an amputated visual culture, viscously cut off from our artistic forefathers we have every right to lay claim to,” exclaimed Archie Rand, artist and professor at Columbia University. In a passionate and articulate account Rand recounted a sweeping history unknown to many. From the Jewish muralists in the third century Dura-Europos synagogue to Camille Pissarro, one of the founders of Impressionism and an important influence on Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Cezanne, Jews have played an important role in the visual arts.

Rand demanded that we recognize and capitalize upon this crucial role especially in Jewish education. Concerning the New York School of Abstract Expressionism, easily the most important movement in mid-twentieth century culture, he noted that “A significant percentage of the important artists were Jews.” “We need to celebrate the Jewish artists” Rand demanded of an appreciative audience at the ATID (Academy for Torah Initiatives and Directions) conference held at the Center for Jewish Culture on Sunday, November 9, 2003. This conference, “Creative Spirituality: Jewish Education and the Arts” organized by Rabbi Chaim Brovender, president of ATID and for many years Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat HaMivtar (Brovenders) in Efrat, Israel, may be one of the most significant events in the growing reawakening of the Jewish arts.

The gathering, cosponsored by Yeshiva University Museum, brought together practicing artists, yeshiva teachers, museum curators and rabbinic leaders to explore the role and potential of art in Jewish education. Rabbi Brovender linked the unique quality of beauty, found in nature or created artworks, to the uniqueness found in the truth embedded in Torah. Paradoxically neither is ever totally satisfying; we always feel to experience more beauty and truth. The newness of each encounter adds to the unique quality of each experience in learning Torah and viewing beauty and art. Rabbi Brovender suggested that since the nature of Torah and the nature of beauty have similarities, perhaps the teaching of art could enhance or reinvigorate the teaching of Torah in yeshivas.

Earlier Sylvia Heshkowitz, director of Yeshiva University Museum, related the famous story of Rav Kook’s reaction to the paintings of Rembrandt in the National Gallery in London. Rav Kook was deeply moved by the paintings, marveling at the quality of light that Rembrandt achieved. It seemed to him that Rembrandt had uncovered “a portion of the hidden light of creation.” If indeed Kook’s appreciation was correct that Rembrandt in his creativity had somehow accessed and had communicated a mystical understanding of the light God created on the first day and had set aside for the righteous in the World to Come, art could be considered a vital tool to draw one close to Torah.

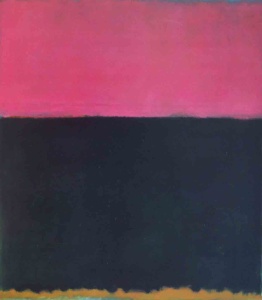

Rabbi Brovender carried the insight even further in an analysis of an abstract painting by Mark Rothko. Brovender commented that the Rothko, one large field of maroon color in the upper half of the painting floating above a darker color on the bottom, demanded our attention. These large luminous works, often thought of as evoking a metaphysical experience, compel our further investigation because, “he poured his neshama into these pictures.” The very difficulty comprehending these abstract images causes us to struggle towards the painting’s meaning, revealing that, according to Rabbi Brovender, “Truth is not simple, even when you are holding on to the Torah.” We must struggle in the creative process of encounter, search and introspection whether we are learning Torah or viewing or creating art. This vital link was explored throughout the conference.

Rabbi Lamm, Chancellor of Yeshiva University and Rosh Yeshiva of RIETS, commented on the traditional Hasidic receptivity to music and art through the concept of avodat Hashem, gashmiut. The notion that we can serve God beyond the mere performance of commandments, through all aspects of our lives including artistic creativity, set the stage for a presentation of Rav Soloveitchik’s views of art and aesthetics by Rabbi Shalom Carmy of Yeshiva University. The Rav’s views of art were complex and not entirely positive. There was the suspicion that art, the aesthetics of both the natural world and that created by man, could overwhelm the intellect and hamper study of Torah. Nevertheless the Rav believed that Talmud Torah demanded imagination, spontaneity and creativity, citing the need for a “polyphonic diversity rather than the discipline of a military march.” Clearly his emphasis on these qualities would imply his openness to creativity as a Torah enhancing value. Most revealingly Rav Soloveitchik felt that in prayer, “Only the aesthetic experience linked with the exalted may bring man into contact with God.”

After a series of hands-on-workshops that emphasized exploration of techniques as “means of expression” and a break for lunch, the conference continued with presentations by educators and artists chaired by Gabriel Goldstein, curator and art historian at Yeshiva University Museum. Tobi Kahn, artist and professor of fine arts at the School of Visual Arts and artist in residence at SAR High School in Riverdale addressed the need for art education in yeshivas. Ninety percent of students “don’t know how to see,” meaning, and are unable to encounter and interpret complex visual phenomena. By teaching students “how to see and raising their visual consciousness” Kahn is expanding both their creative capacity in the visual world and in all areas of their intellectual life. For Kahn who advocated visual arts programs in yeshivas over at least the four years of high school “the creative process is a gift from God” whether learning Torah or making a painting. His objectives seemed to address both education of appreciators of art and creators of art. For him “making art is an additional way of davening.” The intimate relationship between creativity and spirituality is paramount.Creative interaction is the central process.

Rabbi Alan Stadtmauer, principal of Yeshivah of Flatbush High School, addressed issues of establishing a realistic curriculum for the study of art in high school, commenting that the study of art exposes adolescents to a certain kind of vulnerability that is common in both experiencing art and seeking spirituality. This sentiment was echoed by Rabbi Moshe Simkovich of the Stern Hebrew High School of Philadelphia. He spoke of a certain nervous suspicion evidenced by parents about the use of art as an entranceway to spirituality. These educators understood that both the use of art as a creative means to access spirituality and as a creative end in itself could be fraught complex issues new to yeshiva education. Yet all agreed that it was well worth the effort to encourage this kind of creativity, at the very least because of its potential for reinvigorating the learning process and connection to Torah.

Towards the end of the afternoon session Archie Rand speculated on the importance of the first Jewish artist, Bezalel. He noted that we are first told about him high up on Mount Sinai, just as God has finished commanding Moses about all the details of the construction of the Mishkan (Exodus 31:1). Bezalel, “filled with a Godly spirit, wisdom, insight and knowledge…” and his assistant Oholiab, “wise-hearted, will craft all that I have commanded you.” Jewish art is born at the very moment we are given the means to serve God. Within moments Moses will descend the mountain and smash the tablets crafted by God Himself. But Jewish art and artists will live on, first in crafting the Tabernacle in the wilderness, then in the Temple and throughout the ages making objects to fulfill commandments, illuminations for countless books, murals and mosaics for synagogues and finally to the cornucopia of Jewish artwork we have today. As a people of the Book, immersed in the ethereal holy Torah, we focus on deeds and concepts, immune to the lure of crass objects and images. And yet Jewish art is the exception, born on Sinai, in which we engage in the aesthetics of the visual world.

The rabbis, educators and artists at this conference believe that the process of creatively engaging in the visual experience, appreciating and making art, can stimulate and nourish the spirituality of Torah. Surly then that same process applied to specific Jewish content, the vast store of Torah, commentaries and Jewish knowledge, can give birth to an art that itself will become a form of Torah learning, a visual Midrash, a visual davening, even a visual Avodat Hashem.