The Art of Tanya Fredman

Acts of Loving Kindness. This mitzvah is included next to Torah study in the precepts that have no limit, as well as the precepts that are rewarded in this World and in the World to Come. This is surely one of the choicest mitzvahs available to us in our daily lives. We are told that its object is the rich and poor alike, the dead as well as the living. It is expressed in personal effort and involvement in the quietest ways imaginable. And perhaps most surprisingly, it is found in the art of Tanya Fredman.

Fredman grew up in St. Louis and attended an Orthodox day school and then went on to Brandeis to study studio art and Near Eastern and Judaic Studies. After graduating with highest honors she volunteered at the Yemin Orde Youth Village in Israel for three months in preparation to work in a new Youth Village project in Rwanda. The Yemin Orde Youth Village was founded in 1953 to help Holocaust orphans and immigrant children. It developed a classic repertoire of programs to salvage and repair terribly traumatized children. More than fifty years later it continues to serve orphans and children in need from around the world, shaping their Jewish and Israeli identities. Yemin Orde has supported other projects, notably the Agahozo Shalom Village in Rwanda. This special project of the American Joint Distribution Committee and the Heyman-Merrin Family Foundation (under the direction of attorney and philanthropist Anne Heyman) is an orphanage for victims of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. It is directly modeled on the Yemin Orde Youth Village in Israel.

We all know the history of the Holocaust. What about the 1994 genocide in Rwanda? It unfolded before an uncaring world’s eyes as a result of a long and complex process in post-colonial Africa. The strife was between the Hutu majority and Tutsi minority. In the 19th Century the distinction between these two ethnic African groups had been diminishing and practical coexistence flourished. Under Belgian colonial rule (1919-1962) the Tutsis were chosen as the privileged class and tensions and violence grew. Once independence was won the oppressed Hutu seized power and in turn oppressed the Tutsi, causing a Tutsi exodus and diaspora. After years of propaganda and agitation a civil war ensued until a 1993 ceasefire temporarily halted the violence. Then on April 6, 1994 the plane carrying Rwanda’s Hutu president was shot down. This one act triggered a “Final Solution” of the Hutu government, death squads and ordinary civilians slaughtering the Tutsi minority. For the next 100 days the most brutal form of genocide using machetes, clubs and mass rape was perpetuated against the Tutsi and their Hutu sympathizers. 800,000 to one million people were murdered. In reaction to the genocide the Tutsi diaspora military force invaded and seized power on July 17, 1994. It established a government of national unity and has worked hard to foster reconciliation between the Tutsi and Hutu, starting with a practical ban on such tribal distinctions. Over the years progress has been made at forging a national Rwandan identity without ethnic distinctions. It is in this context that Agahozo Shalom Village was founded in 2008 to serve orphaned and vulnerable youth.

As an art educator, Fredman learned the techniques and philosophy of Yemin Ode and was ready to involve her Rwandan kids in communal projects to work together as individuals and express their unique national culture. Creating art together would become part of their recovery from the terrible trauma of genocide. At Agahozo Shalom she taught the high school age students to begin to express their own ideas and learn how to make images that reflected them as individuals. Getting the students to feel they had the right to do something different and unique was initially a struggle that expressed a cultural conservatism and personal hesitation reflective of their traumatic pasts. In the eight months she was in Rwanda she directed the children and staff to create a 30’ X 86’ community mural in acrylic on the concrete wall of the Edmund J. Safra Community Center building. The bright African colors and joyous images expressed the common aspirations and budding visual creativity of her youthful charges.

While Fredman was teaching and nurturing, she was, like all teachers, learning a great deal from her students and fellow staff. Her desire to use art as a way to bring different people to see one another in new ways had a profound effect on her as she made drawings of the staff responsible for the children. Many of the women were survivors of the genocide and rapes and, as she drew their portraits, their stories would slowly emerge as would Fredman’s own reaction to their recent history. They immediately related to her positively, both as a white woman and as a Jew. Some had never seen a Jew before and, as black Catholics and Seventh Day Adventists, easily understood a religious person’s relationship to God. Perhaps most importantly, they sensed a kinship between their country’s terrible history of genocide and the Jewish Holocaust. A surprising bond of shared experience (real and imagined) quickly formed.

Once Fredman had returned from Rwanda she began working on paintings that explored her experiences. She had fallen in love with African fabrics and quickly utilized them in portraits to capture the stories of the individuals she had drawn and gotten to know. Most poignantly were the works she did of “Mama Anny.”

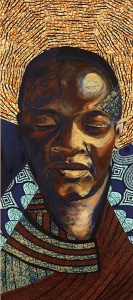

Mama Anny 1 (2010) is a monumental portrait of one individual who came to represent all of the women survivors. Solidly planted on a low stool she is concentrating on a writing tablet, a pen in one hand and a cellphone in the other. We cannot make out what she is writing but her self-absorption leads us to experience its gravity and importance. Her form fills the entire canvas, a secure presence even though most of her figure is in shadow, perhaps alluding to her painful past. On a separate panel next to her is a rich fabric canvas with an evocative acorn pattern, relating in color and texture to her low table and alluding to her fertile seed, her students, who will grow up to be strong oaks someday.

Mama Anny 2 (2010) marks the transition from African to African/Jewish thematic emphasis in Fredman’s paintings. Now her subject gazes directly at us, shielding her face from the bright sun of her culture. Embedded in the background are words from the Rwandan national anthem and “Woman of Valor” from Proverbs. She confronts us as a deeply expressive individual striving to connect even as we see her shaped by national identity, and empathy and affection for her Jewish portraitist.

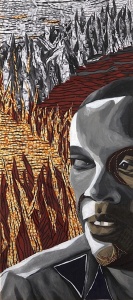

Early in 2011 Fredman plunged into a full-blown Jewish theme in an African context, The Four Sons of the Haggadah. Each oil painting is heavily collaged with African fabrics and presents a single portrait of each “son,” exploring responses to the genocide through their attributes. Actually the portraits are simply different versions of one woman’s portrait. In Rwanda almost all the women wear their hair short and so gender is hard to ascertain by hairstyle. And of course “The Four Sons” represent four children, equally sons and daughters.

Wise confronts us head-on, steadily looking into our eyes even as the background patterns penetrate his head; he is unafraid and strong. Raasha (Wicked) presents a partial profile, furtively glancing to the side and seeming to ignore the powerful patterns of marching figures and flames. The deep red earth behind him suggests a military beret as well as the triangular patch on his shoulder, both echoing the uniform of a government perpetrator. Tam (Simple) is passive with her eyes closed, receptive to the surrounding patterns and

yet little affected by them. Finally She’eino Yodea Lishol (Does not know how to ask) turns away from us, defeated with threatening leaves and flames hovering over her. She cannot confront the peril and will have to be gently guided to deal with the challenges to come. As a series the Four Sons is a highly successful integration of the Rwandan genocide with a deeply Jewish subject. Fredman has bridged the cultural gap between Rwandan history and Jewish history, utilizing African color, pattern and faces to eloquently speak of both peoples’ suffering and hope for redemption.

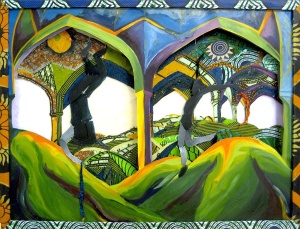

Since the theme of national redemption runs deep in both Jewish and Rwandan thought Fredman explored the mechanics of the process in 3 dimensional sculpture called And It All Turned Upside Down (2011).

Made of fabric, oil paint, acetate, wire and wood, the piece celebrates Purim seen through the lens of an imaginary Rwandan landscape and architecture. The reference is to the word “nehefoch” or “was turned around” in Megillas Esther 9:1 and 9:22; referring first when the Jews prevailed against their enemies and then when the days of sadness were turned into days of gladness. Obviously the Rwandan recovery of a positive national identity after the horrific 1994 genocide easily parallels our salvation from the wicked Haman.

Over rolling lush green hills an arched pavilion echoes African colors and patterns. Two puppet-like figures are suspended in this theater set, one dancing while the other is upside down, reflecting the playfulness and topsy-turvy nature of the Purim holiday.

Fredman is involved in another recent project that looks even deeper into the Rwandan experience. Project 100 Days is anticipated to be 100 acrylic on canvas pieces that will explore the links between the 100 days that is now a Rwandan National Remembrance commemorating the genocide and the parallel season of partial mourning between Passover and Shavuos, the Omer. So far she has created four sets of 4 mostly abstract paintings, each reflecting a specific theme where the Jewish calendar intersects with the Rwandan: Passage of Time, Memory, Seeing the Other, Death of the First Born.

In depicting the complexities of the Rwandan experience through reflections of Jewish subjects and vise-versa, Tanya Fredman has attempted something that is unique in Jewish art. She has reached outside of traditional Jewish norms to speak Jewishly about another people’s tragedies and hopes, and simultaneously uncovered insights into our own history and yearnings for redemption. This is a unique expression of gemilus hasadim, simple loving kindness to other human beings. I think that just taking the time and effort to selflessly care about others elevates us in unimaginable ways. Perhaps this is a entirely new aspect of Jewish art just being explored by this young and rather brave artist.

tanyafredman.com