A Stitch in Jewish Time: Provocative Textiles

Textiles as a Jewish art medium have a long and distinguished history, frequently the sole surviving artifact testifying to a community’s existence and history. Elaborate paroches from 17th century Italy still proclaim a rich and artistic love of the Torah ark so prized by Italian Jewish communities that are now but distant memories.

So too the Torah itself is garbed by elaborate 17th century mantles from Bavarian communities long forgotten. We have plentiful 18th and 19th century works of fabric art from the far reaches of Persia, Turkey, the Middle East and all across Europe documenting Jewish visual creativity. Almost all of this Jewish art is of objects meant to be used; Torah curtains, mantles, binders and cases, matzah and challah covers, covers for reader’s desks and other synagogue furniture, processional flags, rugs (especially Turkey and Persia), prayer shawls and bags for shawls and tefillin, wedding canopies, wall coverings and table cloths. Textile art is perhaps the finest example of the ideal marriage of the utilitarian with the aesthetic in Jewish art.

A Stitch in Jewish Time, currently at the Hebrew Union College Museum and boldly curated by Laura Kruger, is for the most part a daring exception to this history. These works, all created within the last 30 years, are primarily not utilitarian. Building upon the vast foundation of Jewish textile creativity, these works are overwhelmingly conceptual artworks, firmly set within a postmodern context. Their power stems from the artist’s ability to coax enormous meaning from the treads and stitches of ordinary fabric seen anew.

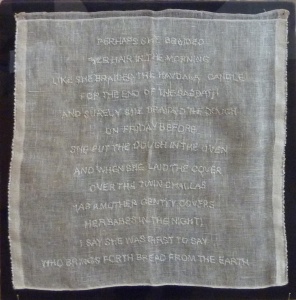

Among the 40 artists represented some stand out with their conceptual urgency. Helene Aylon’s The Foremother’s Challah Cover struck with an uncommon force. A text is simply embroidered on linen in a passion that molds the Shabbos with the everyday work of women’s hands:

“Perhaps she braided

Her hair in the morning

Like she braided the havdala candle

For the end of the Sabbath

And surely she braided the dough

On Friday before

She put the dough in the oven

And when she laid the cover

Over the twin challas (as mother gently covers her babes in the night)

I say she was the first to say

Who brings forth bread from the earth.”

The fabric is carefully embroidered with a deeply sensitive text, much as the braiding of hair, candle and dough impose an elaboration upon a primal element, a simple substance made wonderfully complex and beautiful by the work of an Aishes Chayil.

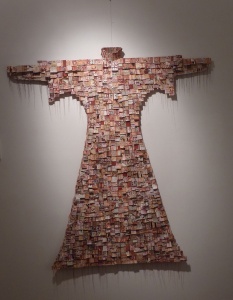

From Sabbath facilitator to victim of male cruelty, Andi Arnovitz’s Coat of the Agunah (2010) reminds us of the unsolved conundrum of recalcitrant husbands in failed marriages. Arnovitz creates a mythical coat that a woman so debased and subjected as an agunah might very well wear, a composite of hundreds of images of ketubot that ostensibly stand to protect a bride, now utilized to compound her exposure and debasement.

Jewish textiles as symbolic clothing finds other expressions in this exhibition, especially as a cloak for the Torah itself in She is a Tree of Life (2000) by Temma Gentles with Dorothy Ross. The artists state that “Because Torah, wisdom, and understanding are feminine nouns in Hebrew, [therefore in this work] the Torah scroll is dressed as a 17th century Italian bride in the elaborate Baroque manner.” The artist embeds an abundance of symbolism in the Torah “garment;” pomegranates to bespeak commitment to mitzvoth, crimson ribbons to repel the evil eye and seven barley stalks around the hem to evoke Shavuot and counting the omer. In a somewhat magical moment the Torah thus clothed begins to look like an actual person, doubly worthy of our respect and honor.

In another highly conceptual work Yeshiva In Between (2008), Jacqueline Nicholls creates a visual midrash based on Niddah 30b. We learn there that a fetus spends its time learning Torah but is compelled to forget it all once born. According to Nicholls we “spend our lives retrieving the knowledge that was once ours.” Thus for the artist a woman’s pregnant body is “a makom Torah, a primal beit midrash for the fetus,” suspended between the Yeshiva Shel Ma’alah of heaven and the Yeshiva Shel Matah rooted in the mundane world. This sacred pregnant womb is represented by a kind of corset, made of open weaving able to contain the fledging life being filled with life-sustaining Torah knowledge.

On the opposite end of life’s spectrum Lisa Rosowsky creates Designated Mourner (2008), a costume based on a 1901 French mourning dress. The text panel provides the context in a Wallace Shawn poem (and play); “I am the designated mourner… Oh yes, you see… someone is assigned when there’s no one else.” While on the front of the black velvet dress is the first few words of the Kaddish, the long shawl that falls down the back depicts ghostly images of Jews being marched to their deaths in the Holocaust. Rosowsky assembles disparate elements to suggest a new Jewish ritual, a mourning dress for someone to wear as a designated mourner for the victims of the Holocaust who have no survivors to say kaddish for them. Of course we actually do this when we say Yizkor, but here the artist ‘clothes’ the concept, thereby making it tangible and convincingly moving.

Carol Hamoy’s Ten Plagues (2009) also utilizes symbolic clothing to fashion a commentary on the Torah’s narrative of the Exodus. Ten 1940s vintage nurse’s uniforms float mysteriously above the floor, suspended from the ceiling. Each has an updated “plague” embroidered across its chest; Heart Disease, Famine, War, Infertility, Bigotry, Homelessness, Cancer, Aids, Pollution and Drought. Repositioning the Biblical narrative to the beginning of World War II, a war very much our own, she sees all of mankind suffering from Divine afflictions and tragically helpless to intervene as much as these heroic nurses might try.

Memory and Jewish women’s identity are movingly summoned in Women of the Balcony IV (2008) by Jane Trigere. Dedicated to German-Jewish refugee women who attended services at Ohav Sholaum Synagogue in the Inwood section of upper Manhattan, the artist rescued fabric from the cushions made by and then left by these very individuals. In its own way this fabric told a very personal story of these women, now finally safe in New York from Nazi oppression. Trigere made the fabric into sculptural hair, their faces now covered with fragments of the German text of tehinnes, prayers specially made for women in the vernacular. These nine heads affixed atop a symbolic mehitzh forcefully summon memories of these women, their lives and struggles, now vanished from the abandoned shul.

Finally, some of this splendid fabric art is just about the joy of seeing. Laurie Wohl’s Peace Like a River (2010) is based on four verses from Tanach; Isaiah 66:12; Ecclesiastes 1:7; Song of Songs 4:15 and Psalm 36:10. Linked together by the hope that peace that can at one time flow as effortlessly and bountifully as a river, the 84” tall wall hanging undulates like water itself and is simply a visual feast. The sumptuous pastel colors are set off by bands of gold and silver text in English and Hebrew that winds sinuously across the glittering surface. The visual joy Wohl creates anticipates the emotional joy we so yearn for when peace will reign supreme.

A Stitch in Jewish Time gives us much to ponder about the entire corpus of Jewish life and art. Indeed, in its determined artfulness that nonetheless is firmly rooted in Jewish history and ideas, many of these works actually do border on the utilitarian. It turns out that its practical use is as Jewish art is that it is meant to inspire thought, reflection and joy in our visual expression, fully contemporary and provocative.

A Stitch in Jewish Time: Provocative Textiles

Hebrew Union Collage – Jewish Institute of Religion Museum

One West 4th Street, New York, NY