A Mohel’s Siddur by Aryeh ben Judah Leib

Imagine you are a mohel and, thank God, business is booming. It’s a good living and you even have time to sit and learn in between the jobs that seem to crop up at least once a week. Also you do a bit of doctoring and tutoring a few children in heder. You think, “perhaps I should have a siddur to replace my father’s worn-out printed volume that he got from his father and then from his father…oh so many years ago. Here I am in Trebitsch…who can help me find something…nice. Oh, I know, Aryeh ben Judah Leib. He is getting really famous for making hand written books with beautiful decorations over in Vienna where he has set up shop. He makes his seforim for important people, even those Yidden who serve at the royal Court. Just like they used to do maybe two hundred years ago before we had Hebrew printing. Why not, I’m doing well, doing God’s work. It’s a hiddur mitzvah.”

And so a patron of Jewish art is born. Indeed, Aryeh ben Judah Leib of Trebitsch was a Moravian scribe living in Vienna who started what would become a major movement in Jewish art; the return to the handwritten illuminated Hebrew manuscript in the 18th century. His clients were frequently men of power, Court Jews who could afford a handwritten sefer. But occasionally, a simple man like our mohel approached him for a special commission. Indeed, the manuscript we have is a siddur with numerous piyutim and commentary for a mohel by David ben Aryeh Leib of Lida (1650-1696), nothing terribly fancy or elaborate, except for one rather unusual illumination right at the beginning.

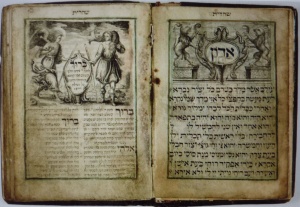

The siddur, currently in the Braginsky Collection (reviewed here) is called “Sefer Sod Adonai im Sharvit ha Zahav (Book of the Lord’s Mystery with the [commentary] Golden Scepter.” It was copied and illuminated by Aryeh ben Judah Leib of Trebitsch in 1716 and features a title page showing three men and two women in a synagogue setting. After that is the prayer Adon Olam illuminated with two rampant lions unfolding a cartouche with the Hebrew word Adon” inscribed. Next are the first morning blessings: “Blessed are you Hashem… regarding washing the hands. Blessed are You Hashem…who heals all flesh and is wondrous in His acts.” The blessing on washing the hands is surrounded by an illumination that depicts an angel on the left and a young man carrying a big fish on his shoulder on the right. Rather surprisingly the subject is from the Book of Tobias, part of the Catholic cannon and known as a book of the Apocrypha (from the Greek meaning “hidden things”).

What’s this subject doing in a pious Jew’s siddur?

First of all the subject, the Book of Tobias, while not included in the Jewish canon, is distinctly Jewish. It was composed in Aramaic sometime between the 4th and early 2nd century BCE. Four copies in Aramaic and one in Hebrew were found in the Qumran Caves among the Dead Sea Scrolls. According to scholars several medieval Jewish versions survive and there is evidently a shortened version of the tale in Midrash Tanhuma (Encyclopedia Judaica). It even surfaces in an early painting of Moritz Oppenheim, “Return of Tobias” 1823. It is unknown why it was not included in the canon although the Mishnah Yadayim 4:5 seems to imply that books included in the canon can be written in Hebrew, or Hebrew and Aramaic, but not totally in Aramaic.

Set in Nineveh, capital of Assyria, around 722 during the exile of the ten northern tribes (2 Kings 17:6). Tobias was a deeply pious Jew of the tribe of Naphtali, zealous in observance of all the mitzvahs, giving charity, keeping kosher and being especially careful about the mitzvah of burying the unclaimed dead even in the face of persecution. In spite of his selfless piety he was blinded in an incomprehensible divine test similar to the one we see in the Book of Job.

Tobias had a son also named Tobias who was raised to be as pious and righteous as his father. He meets a stranger, actually the angel Raphael, and together they set out on a journey to recover a loan for his aged and blind father. As they rest by a riverside Tobias is attacked by a fierce fish, only to be saved by his new friend who teaches him to use parts of the fish in miraculous ways. They come to the distant house of his father’s brother and discover the man’s only daughter, Sarah, has been preyed upon by the vicious demon Asmodeus who has slain her seven prospective husbands each on their wedding night. Tobias destroys the demon and frees the young woman to marry him. They finally return to his old father and mother and cure his blindness with the gall of the fish. They all thank God for their deliverance and the angel now reveals himself, blesses them and departs. The book ends with a prophecy of their return to Israel and Jerusalem.

The story is a tale of deep faith, filial devotion and divine assistance. It relates two tales of suffering 1) Tobias’ blindness and 2) Sarah’s demonic curse that are resolved by a pious Jew’s constant faith and divine intervention by the angel Raphael. This parable of individual redemption reverberates in national redemption that was witnessed in the return of the Jewish people to their land and the building of the Second Temple.

The image in the mohel’s siddur is artfully simple, showing the angel in typical Baroque costume, staff in hand, accompanying the steadfast Tobias dutifully carrying the fish and accompanied by their faithful dog in the lower right corner. In the context of the Tobias story it is an image of determination to cure the ill and render kindness and mercy for their family that need help. In the context of a book on circumcision it proclaims that circumcision is in fact a cure, making the child fully whole and fully Jewish. It is of course symbolic of our partnership with God, our role in completing God’s creation of the child with the mark of the Covenant.

The featuring of the archangel Raphael in this narrative is especially apt since he is traditionally associated with healing by his name alone, Raphael = God is healing. Even more revealingly Raphael is cited in the Talmud, Yoma 37a, as one of the three angels who visit Abraham as he is recovering from his circumcision. In the much latter literature of the Zohar “he is the angel who dominates the morning hours to bring relief to the sick and suffering” (Encyclopedia Judaica). Suddenly the use of Raphael couldn’t be a more apt image to have in a mohel’s siddur. One almost wonders why the Book of Tobias wasn’t used more often in Hebrew illumination.

Perhaps the fact that Jews did not venerate its text while the Christians did chased off Jewish artists and thinkers from utilizing the rich material found in this abandoned Jewish book. Not surprisingly, following Jewish tradition, in Christian lore the angel Raphael is the patron saint of apothecaries and physicians, guardian saint over children, also watching over travelers. But for Aryeh ben Judah Leib of Trebitsch, the man who started a rebirth of Hebrew manuscript illumination, it was fair game to create a totally unique and deeply meaningful image for a mohel’s siddur. We are blessed with his creativity and insight.

I am deeply indebted to curators Emile Schrijver and Sharon Liberman Mintz for their research in the catalogue Highlights from the Braginsky Collection. I especially thank Sharon Liberman Mintz for directing my attention to this fascinating manuscript.

A Mohel’s Siddur by Aryeh ben Judah Leib

From the Braginsky Collection

Braginskycollection.com

Photography and Website design by Ardon Bar-Hama