After the Catastrophe: Prelude

The Holocaust, dominating Jewish Art for much of the late 20th century, is arguably the first form of Jewish Art to penetrate the mainstream cultural dialogue. The division between Jew and non-Jew in the arts begins to be erased. This unique event aimed at the destruction of the Jews quickly became the universal symbol of intolerance, hatred and racism for modern culture.

Jewish artists anticipated the Holocaust as early as Samuel Hirszenberg (1865-1908) in his painting, The Black Banner (1905, Jewish Museum). The image of hordes of Hasidim fleeing in horror, bearing the coffin of a victim of Russian anti-Semitic violence bears testimony to the relentless cycle of murder, rape and pillage against the Jews of Russia and Poland from the pogroms of 1881-82 to the Kishinev and Zhitomir massacres of 1903 and 1905. Equally prophetic is some of the graphic work of Ephraim Moshe Lilien (1874-1925). In one of his works he fashioned a poster to commemorate the Kishinev Pogrom in which a venerable sage is burned alive. Bound by ropes and his own tallis, the frail figure is comforted by an angel who rescues a Torah scroll from him as the flames consume him. While this image summons the famous Talmudic story of Rabbi Akiva’s death during the Hadrianic persecutions, it also references a contemporary event recorded in David Pinsky’s 1903 play, The Last Jew.

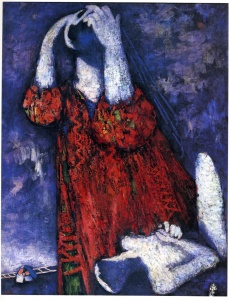

By the late 1930s Marc Chagall could anticipate the impending catastrophe by utilizing symbols of suffering indigenous to Christian Europe. The Fall of the Angel (1923-1947) depicts a world coming unhinged by unseen forces, a universe in disarray. As a female angel falls from heaven followed by a grandfather clock (time is running out…) a Jew flees with a Torah scroll off the left edge of the canvas. Looming in the dark background is an incongruous crucifixion as symbol of persecution itself. Perhaps as a reaction to Kristallnacht, Chagall’s The White Crucifixion (1938, Art Institute of Chicago) Judaizes Europe’s most cherished Christian icon. The shul is burning, the shtetl houses overturned and the Jews are fleeing with their belongings and the holy Torah. The crucified Jesus becomes the Jew clad in a tallis. Chagall has attempted to turn Christianity on its head by utilizing Jesus (the suffering of one) as the symbol of the many, a symbol of the Jewish people. The truncated ladder falls short of the victim and, in a prescient symbolism, a six candle menorah burns at the foot of the cross, one candle already extinguished. The Shoah was just beginning and yet in this complex and disturbing painting Chagall sensed what was to come.

Behind the Wire

Amazingly art was made in the war time ghettos, frequently as a means of psychological self-defense. While the same dynamic operated in the concentration camps, the terrible logic of annihilation dictated that much of the art that survived was by non-Jews. Nonetheless a substantial number of artworks by Jews survived the Holocaust as testaments to individual lives, documents of what occurred and as a kind of heroic resistance.

One example is Halina Olomucki (b.1921) who was a young artist when her family was forced into the Warsaw Ghetto. There she made numerous drawings, documenting deportations, the ghetto revolt and the liquidation of Dr. Korczak’s orphanage. She was deported in 1943 first to Majdenek and then to Auschwitz-Birkenau where she made over 200 clandestine drawings in the camps. She survived (as did many of her drawings) and eventually she immigrated to Israel in 1972. Fulfilling her fellow prisoners’ demand, “draw me, so that at least we will go on living in your work,” Smuggling Food, 1943 stands as a testament to a single human life.

After the Catastrophe

Mordechai Ardon’s Sarah (1947) is an early Israeli reaction to the Holocaust that harnesses the Biblical metaphor of the tragic outcome of the story of the Binding of Isaac. The events of the Shoah put religious belief under attack. In one midrashic version of the story, Isaac is actually slain by his father Abraham at God’s command. Ardon depicts this movement of Sarah’s anguished scream over the body of her son on the altar. The shock kills Sarah just as the horrible reality of the millions slain in the Shoah extinguished the faith of untold thousands. Nonetheless, with the exception of the figure of Job, the blameless righteous man tested by God, Biblical subjects have been underutilized in addressing the Holocaust.

In America Hyman Bloom (b. 1913) responded to early accounts of the liberation of the camps with a gut-wrenching series of paintings of dissected rotting corpses and body parts. In a perverse reflection of the mountains of dead victims Bloom chose not the emaciated figures of the first photographs. Rather paintings like Female Corpse (1944-1945) depicts a kind of endless death, explicitly showing a festering decay that simultaneously addresses the fetid rot of European civilization and the terrifying concept of death as an almost permanent presence in a post-Holocaust world.

Jacques Lipchitz’s Prayer (1943) offers a chilling parallel to Bloom’s dissecting room vision. A baroque figure of a Jew performs the kapporah ceremony, swinging a live chicken over his head (prior to contributing the bird to charity) as a symbolic expiation of individual sin through the sacrifice of the bird. What occurs here in Lipchitz’s sculpture is that the Jew is himself eviscerated, his guts ripped open by the futile attempt at repentance.

Ben Shahn (1898-1967) was one of America’s most prolific graphic artists (with a pronounced left-wing vocabulary), nonetheless he “created one of the most important bodies of religious Jewish art by any American artist through the 1950s and 1960s…” (Baigell). In Allegory (1948) The Lion of Judah jealously guards a pathetic pile of bodies pointing to both the Holocaust and the creation of the State of Israel in May 1948. There is a deep irony in the image of the lion; ferocious, breathing fire, the timeless image of the protector of the Jewish people. And yet the king of the beasts is emaciated, ribs exposed even as there are so few survivors left to guard.

Survivors

Many survivor artists, also reacting to the conformist “melting pot” social norms of post-war era, found it almost impossible to confront the Holocaust and for years suppressed these painful subjects. Zoran Music was arrested in 1943 and interred at Dachau. He did over 200 drawings there. Thirty-four survive. After liberation he continued his art career in Venice and Paris. In 1970 he began a new series that was to become We are not the Last. While superficially they are simply a continuation of the harrowing drawings he did of the dead and dying while an inmate, the new series extends Holocaust representation to a more fearsome level. By the deliberate confusion between the dead, dying and those who might survive, Music accentuates and extends the factories of death to the killing fields, ethnic cleanings and genocides of the late twentieth century. From a non-Jewish perspective the issue in a painting like Head (1974) is not the subject of the slaughter, but the methodology itself.

Samuel Bak (b. 1933) managed to survive the invasion of the Nazis, the Vilna ghetto and a labor camp. By the 1970s the memories could no longer be suppressed. One major element in many of Bak’s paintings is the depiction of buildings. Ghetto (1976) is a portrait of an imagined cluster of houses set in a barren landscape. It presents an aerial view of a set of children’s building blocks that becomes a ghetto. The interior courtyard formed in the shape of a Star of David conveys the grim despair of this imprisoned life.

In a recent series of paintings, Return to Vilna he confronts his return to his birthplace for the first time in fifty-seven years. A group of ten paintings of The Trees of the Forest Ponary is a haunting memorial to the victims of the mass executions outside Vilna. Under the Trees (2001) achieves a monumental scale and vivid impact as an image of a world radically displaced. Through the medium of straightforward realism the image of trees that fly and float like awesome clouds is simultaneously credible and yet profoundly disturbing. The jagged boulders, bullet ridden and blood stained, rise up in a doomed struggle to free themselves from the corpse filled earth. This bucolic view, complete with pretty pink clouds at the horizon, seems to have captured the moment in time when nature was defiled by mass murder.

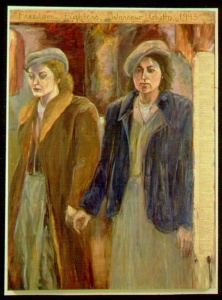

A similar survivor experience is seen in the work of Diana Kurz, born in Vienna, Austria, and who escaped with her parents. She became an artist and it was a chance visit to an elderly aunt in California in 1989 that launched her on a ten year exploration of the Holocaust in her art. Her work is primarily an act of documentation and testimony. Working from photographs of her family and other Jews she constructs large scale painted memorials that include textual declarations. The somewhat awkward depictions, as if the tattered photographs were brought back to life through a colored looking glass, fill the image with a tender concern for the subjects. Kurz is painfully aware that the few photographs we possess of these people may be the only evidence that they existed. Even after their murder they are on the very edge of obliteration and Kurz is determined to pull them back from the edge and make a memory, make us understand that a real human being once existed and was tragically murdered. Her work, such as Freedom Fighters (1999) frequently concentrates on women and children, and demands that we feel the loss even if we never knew the individuals. Her creative act claims that we are all family.

Others

Art Spiegelman’s Maus: A Survivor’s Tale marks an important rupture in this particular lineage of survivor testimony. It presents the testimony of Vladek Spiegelman through the voice and eyes of his son, Art Spiegelman, in the unorthodox medium of the graphic novel, known as commix. A number of subsequent artists have utilized this medium in Holocaust Art. In this shift from authentic testimony to a profoundly mediated interpretation we are twice removed from the event itself. The aging and eventual demise of the survivors makes direct access to living testimony a growing impossibility. If we in the late twentieth century are to approach the Holocaust the only access is via art. Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, is a two-volume book of close to fifteen hundred comic book style frames and was published in 1992 after thirteen years of drawing, interviews and research. It transforms the historical process of testimony into an artistic process in the search for a larger meaning.

Natan Nuchi, an Israeli artist living in New York, has been painting single figures that evoke Holocaust victims for the past twenty years. As a son of a survivor his youth in Israel was dominated by the oppressive silence about the immediate past in Europe. The shame of Jewish victimhood was unconscionable for most Israelis. In reaction, much of his creative life has been spent in trying to extricate himself from under the burden of the Six Million. Paradoxically, he has been continually drawn back to the victims by painting them one by one. There are no identifying marks or symbols to link them to the Holocaust, only the emaciated specter of suffering that proclaims our era. For Nuchi their anguish is universalized as an accusation against all because the evil that the Shoah unleashed continues to live in the soul of man. Once perpetuated it is forever possible to be repeated and for Nuchi, that has changed everything. He has brought the millions unburied back to haunt our consciousness, refusing to mitigate the tragedy. His unflinching paintings tell the story that evil won and the majority of Europe’s Jews were murdered. He cannot avert his eyes.

There are many other artists who have made Jewish art based on the Holocaust in the last sixty-one years. Some are famous like George Segal and Joan Snyder, others less known like Leah Ashkinazi and Yonia Fain. In a way this subject has become a common language, a remarkable starting point to probe the conundrum of life in our times. From these events there can be no easy answers. And that fact challenges a multitude of cherished icons. Western rationality and the holiness of Heaven cannot escape its scrutiny.