Harry McCormick’s Paintings: A Unique Jewish Genre

At the Chassidic Art Institute one artist, Harry McCormick, has rather amazingly fathomed the authentic heartbeat of the individual Jewish life. This exhibition, running until July 25, shows a mere 16 paintings, but within the major works he is showing, six works reveal a deeply perceptive and sensitive chronicle of Yiddishkeit.

As curated by Chassidic Art Institute director Zev Markowitz, the paintings delineate a narrative arc around the gallery: the warmth of the Jewish family unfolds into the blessings of Shabbos and then blossoms into blessing the sun, a mitzvah available only once every 28 years. Moving beyond this sacred familial foundation we see one Jew standing alone in a mystical shul in Safed and then in Jerusalem; finally this Jew encounters a rabbinic mentor in a synagogue in New York. Quite a journey in one exhibition.

McCormick has had a successful career as an artist for most of his adult life, creating what is called genre art. While genre paintings, i.e. pictorial representation of everyday life with everyday people, can be found throughout all art history, it blossomed as a distinctive movement in the 17th century Dutch Golden Age of painting driven by the rise of the middle class. Its most famous practitioners include Brueghel, Vermeer, le Nain, Watteau, Fragonard, Chardin, Hogarth; right up to Bonnard, Hopper and even Norman Rockwell.

Over the years McCormick has specialized in depicting interiors with people, such as a decades long series depicting bars from around the world and their patrons. A quick glance at his website (www.mccormickstudios.com) reveals that these works are often penetrating sociological studies of the complexities of human relationships played out in extremely public spaces. Another recent fascinating series is of people looking at famous paintings in museums. While at first glance one might think that all he is doing is making an accurate representation of something he witnessed, a closer examination reveals that this is far from the truth. Aside from my discussions with the artist that revealed his complex working methods, we can immediately see that he takes enormous liberties with the actual size of many very famous artworks, all of which serves to heighten the intensely psychological narratives that play out in public art spaces. His encounter with the Jewish world is no less insightful.

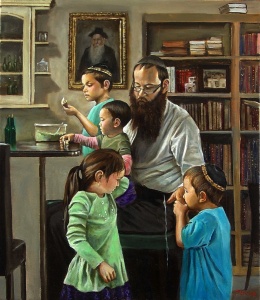

Rabbi Lieberow and Family is a study in mystery cloaked in the ordinary. At first it seems like a charming family portrait of a father with his 4 children. And yet upon close inspection each child is immersed in his or her own world as its father carefully supervises. The two boys on his lap are occupied with stuff on the table; one is studying a

piece of pita about to be consumed while his younger brother plays with a tiny toy. The boy in the foreground is intently kissing his father’s hand as his sister quizzically looks on. The heartwarming dynamics are complex and intriguing, especially when you realize that this image is the result of dozens of different studies, drawings and images painstakingly stitched together to create the illusion of a casual homebound scene. The painting divides into two parts that continually relate to each other. On the left the 3 figures ascend to the boy about to eat and finally to the ancestor portrait on the wall behind him. He is the link to the past, a piece of history in the making, while on the right there is the realm of Torah knowledge represented by the laden bookcase and the rabbi himself. The two books at the very top seem to symbolize the core of this family, the man and wife overseeing the unfolding family below. And of course the mystery is, where is the wife?

In the next painting that the mystery continues. Friday Night Candles presents the anticipation created by the onset of the holy Shabbos. This painting presents an almost perfect balance. The figures are in the exact center; in the middle ground of the image, spatially delineated by the strong foreground table, chair, and side table and the implied distance outside the curtained glass doors. Here an older sister is lighting Shabbos candles with her two younger siblings. She has covered her hair with a delicate lace scarf and affectionately holds one sister as she lights the first of two candles. She will light the second one and then cover her eyes to pronounce the blessing. It is interesting to note that the midrash Eliyahu Rabbah understands the custom of two candles as representing the husband and wife. This subtle interpretation effectively links this painting’s symbolic parents with the two books in the previous artwork. And just to heighten the narrative mystery, the empty chair in the foreground, poised at the head of the table, likewise points to an unseen parent.

The third painting, Sunrise Ceremony on the Beach, resolves the mystery of the unseen parents by presenting one complete Jewish family in the midst of a rarely performed mitzvah, Blessing the Sun. Based on the Talmud Berachos 59b and Eruvin 56a as codified in the Shulchan Aruch, Birkas haChama is done once every 28 years to commemorate the creation of the sun when it returns to its original position on the fourth day of Creation, Tuesday. Since the first time the sun can be seen is the following sunrise, it was last done at sunrise, Wednesday, April 8, 2009. Even though it is preferable to do this mitzvah with a multitude of people, here McCormick has chosen to depict just one family to become emblematic for the whole Jewish people. Father, daughter and mother carrying an infant becomes the primordial family upon which the whole future will grow. And as such they occupy the entire left side of the painting, perfectly balanced by the vibrant orb of the rising sun on the right. It is the Jewish family in balance with the God’s creation.

In the next three paintings McCormick narrows his focus from family to the lone individual. He is a searcher of faith and, secured by the refuge of the Jewish family, he can now explore the places where he might encounter God. Naturally the Abuhav Synagogue in Safed is a perfect place to start. The 15th century Abuhav Synagogue is famous for its delicate design and kabbalistic symbolism, allegedly designed by the Spanish rabbi and kabbalist, Isaac Abuhav, the author of the Menorat ha Maor. On the southern wall, facing Jerusalem to the south, there are three holy arks. This was the only portion of the synagogue that survived the devastating earthquake of 1837 and the remainder of the building and all the interior decorations were created after then. At this southern wall, close to the ark, we see the lone figure standing, cloaked in a tallis and deep in meditation. The painting’s harmonious contrasts of blue walls and earth-toned ark are notable for both the calm pensive atmosphere created and the artistic liberty taken since the walls of this synagogue are actually white. Yet the invention works wonderfully, creating an ethereal light and echoing the notorious use of blue on gravestones of the righteous and homes in Safed as well as many kabbalistic formulations such as the techelet of the tzitzit and the blue associated with attribute of Chokhmah in the Sefirot, We have entered a truly spiritual universe.

The Yochanan ben Zakkai Synagogue in Jerusalem is a step in yet another direction. The legendary foundation of this synagogue goes back to the Beit Midrash of the tanna Yochanan ben Zakkai who courageously established the Sanhedrin in Yavneh to begin the reconstitution of Judaism and the Jewish people after the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. The current building was built in the 17th century and was in constant use since then, but was gutted under the Jordanian occupation that only ended in 1967. It has been totally restored and is now back in use. In McCormick’s painting the exact same individual is standing alone in the quiet interior, and yet the effect is deeply different. The confluence of ancient history, religious and physical revitalization drives the psychological narrative. The man is standing between the two giant Torah arks, rooted in their unwavering sanctity, while above him a mystical contemporary painting hovers. In its way the relationship between the painted reality of the McCormick’s image is in radical tension with the depiction of the painted shul decoration. We are unsure which is “real” and which is “fantasy” while actually both are real and true.

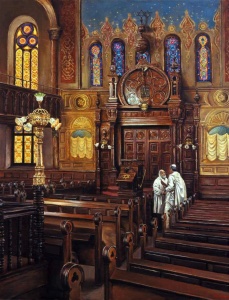

Finally in the Eldridge Street Synagogue we shift into a much more down to earth mode. Warm earth colors vibrate with luminous gold that only allow a few hints of celestial blue in the stained glass windows and painted wall above the carved ark. Our spiritual seeker seems to have come home to a synagogue in which he is not alone. He is now seen with a young mentor who will guide him. Ironically, for all of the artist’s splendid rendering of details and surfaces that place the figures in a very real physical space, the synagogue itself is tragically only a finely wrought museum, no longer used as an actual house of Jewish worship in an area almost totally bereft of religious Jews. Glorious history but precious little Jewish spirituality.

In the quest to create these impressive paintings over the last 2 years Harry McCormick has begun to discover many of his very real Jewish roots, both in his maternal heritage and in artistic insights to the traditions, core values and spiritual explorations prized by the Jewish people. These keystones of Jewish life unfold in his masterful Jewish Genre Paintings.

CORRECTION: The Eldridge Street Synagogue continues to offer weekly Shabbos, Rosh HaShanna / Yom Kippur holiday services and classes under the leadership of Rabbi Abraham Laks and Mrs. Tovah Bookson. For times and information call 917 860 3942. Please forgive the inadvertent error.

Harry McCormick’s Paintings: A Unique Jewish Genre

Chassidic Art Institute

375 Kingston Avenue, Brooklyn, New York 11213; (718) 774 9149

Until July 25