We Are Patriarchs: Paintings by Elke Reva Sudin

One way to understand the biblical is through contemporary eyes, literally. And so artist Elke Reva Sudin has recast biblical figures through contemporary portraits. The juxtaposition is revealing. This extraordinary suite of 11 oil paintings, all created within the last year and a half, marks a courageous departure for this young artist as well as an exciting challenge to fellow contemporary Jewish artists to fully engage the biblical in contemporary terms. The works will be seen at the Hadas Gallery on Myrtle Avenue in Brooklyn until February 24.

Shabbat Afternoon in Leah’s Tent is a lush depiction of a familial universe. The figures, representing Jacob with his first-born Reuven seated on the chairs and Leah, Simon and Levi (I’ll explain shortly), by the couch, are all arranged in the upper half of the image. The bottom is dominated by a busily patterned Persian carpet that combines with the overall fisheye view offering a dizzying impression of their living room. Their lives are rich with complex and interconnected meanings even as the little caged bird makes us pause and consider its symbolism.

In all these paintings the relationship between the biblical title and contemporary Brooklyn portraits is crucial. Here the artist exercises the right to change the gender of the characters in order to insist that the biblical characters and personality traits are not necessarily gender bound. Others might take another interpretive approach and see this scene as Jacob and Leah with one son and two of the twin daughters born to each of Jacob’s wives (except Joseph), as described in Chapter 36 of Pirke de Rabbi Eliezer. In this way the image implies many more siblings beyond the literal pictorial frame. Whichever the explanation, the family depicted is genuine, pious and thoroughly convincing as a modern biblical vision.

Gender migration is not unusual to Judaism. We normally refer to God in the masculine and yet do not hesitate to refer to His Divine Presence as the female Shekinah. So too Sudin interprets the Song of Songs by depicting the great Davidic composition in the guise of a woman sitting with an oud pondering the next song she will compose. The sensitive portrait is of Basya Schechter, leader of the contemporary Jewish band, Pharaoh’s Daughter; here ostensibly depicted as the psalmist David himself.

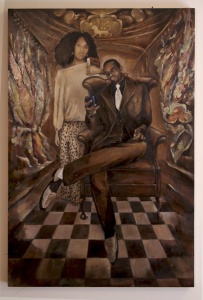

Changing context is of course a fundamental technique to invigorate all too familiar narratives. Here, Joseph in Exile (Joseph and Osnat) forces us to re-understand the puzzling biblical narrative. Joseph is given Osnat, the daughter of Potiphera, ostensibly an Egyptian woman as a wife (Genesis 41:45). An Egyptian woman as a wife! The Midrash explains that she is actually the daughter of Dinah, sent away after the terrible violation of Jacob’s daughter. She has been adopted by Potiphera, the same former master of Joseph. Her pivotal role cannot be overemphasized in that she is the Jewish female presence re-introduced to Joseph’s highly assimilated life. In this painting she is depicted holding a siddur, in effect reminding Joseph of his Jewish roots. The contemporary portrait of this black Jewish couple reverberate back into the biblical narrative; Joseph as a man of power and yet an outsider is vindicated by the confidence of his and his wife’s role in Jewish history.

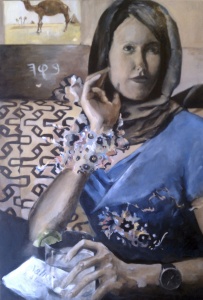

Sudin’s series considers the role of the individual equally with the familial and so her depiction of Rivka at the Well reverberates historically as well as personally. This is a painting consumed by potentiality. Rivka at the Well depicts a contemporary woman sitting at a New York City bar, “Nahor Lounge” waiting for her beshert to arrive. Notice she is adorned with an explosive bracelet and echoed pattern above her heart connoting her eagerness. Her wristwatch tells us that time is a-wasting while the image of a camel (slyly from the packaging of Camel Cigarettes) fleshes out the narrative soon to unfold. But this image is about what is about to happen and how we may prepare for it. It suggests that we should go to the place where possibility exists. This image is a totally unique understanding of the matriarch Rivkah and what she may teach us today.

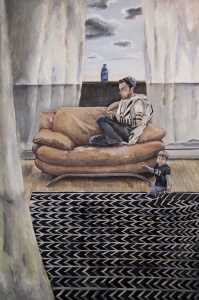

While most of these paintings are clearly non-narrative since they originated as portraits of contemporary Jews, nonetheless there is almost always an implied narrative lurking beneath the surface. Sunday Morning in the Tent of Abraham presents yet another domestic scene crying out to be interpreted (i.e. narrated). Abraham is depicted here concentrating on his prayers while simultaneously keeping an eye on his young son Isaac. The three registers that divide the painting horizontally reflect three very different realms. The lower section seems to reveal a foundation of abstract order, while in the middle section resides human life as it tries to reach out to God. Finally the Divine realm is echoed in the calm beautiful sky. But still there is mystery as Abraham’s head intrudes upon the upper register, just as the child’s leg encroaches on the otherwise symmetrical rug. In the quiet stillness of this scene we are led to think of Abraham, alone in the world in his belief in one God, patiently exploring how to reach out to Him, even as he must be a good parent to his helpless child. And significantly Isaac looks out from the painting, perhaps at us, imploring us to imagine his future. From a contemporary portrait of Jewish father and his child the artist has transported us back to the interior mental landscape of our forefather.

Elke Reva Sudin describes herself as a cross-cultural painter and illustrator whose work explores “the tension between the traditional and the contemporary coexisting in a shared space.” Educated at Pratt Institute she continues to curate exhibitions of other artist’s works as well as founding and running the media outlet Jewish Art Now that aims to “redefine 21st century art for the Jewish community.” While the paintings in this current exhibition certainly successfully reflect these goals, I believe they also open up another fruitful artistic field. It is extremely significant that the depiction of biblical matriarchs and patriarchs is being done by an observant Jew. Many frum artists shy away from pictorial representations of the Avos and Imos, presumably because these individuals are thought of as too “holy” to come under artistic scrutiny. That is, I believe, a mistaken approach. Just as they are closely examined by all of our traditional commentators so as to learn from lives and roles for the Jewish people, so too visual depiction and commentary can be easily as fruitful. Sudin has successfully scaled that conceptual wall to excellent results.

We Are Patriarchs: Paintings by Elke Reva Sudin

Hadas Gallery

541 Myrtle Avenue, Brooklyn, New York

[email protected], 215-704-2205

Until February 24, 2013