Three Faiths at the Public Library

People believe different things and when they group together as religions, they pretty much agree that most of what the other groups believes is wrong. But one thing that unites the big three monotheistic faiths, aside from the ostensible shared belief in one God, is a strong visual tradition found in manuscripts, documents and books.

Three Faiths:

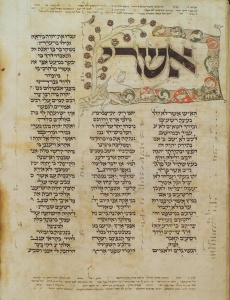

Judaism, Christianity, Islam currently at the New York Public Library at 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue, explores parallel and divergent trends in illuminated manuscripts and books of the last 1500 years from the Library’s vast permanent collection. Most importantly, on the Library’s website there is an online exhibition that allows you to peruse many of the pages in exhibition manuscripts (look for NYPL Digital Gallery) that are not viewable in the exhibition itself (obviously each manuscript can only be open to one page at a time). Also available to view in the Digital Library are related works that the Library has in its collections, such as its 21 decorated ketubot or the 49 illuminated pages of the Tanach written by Joseph of Xanten, Germany in 1294. To say the least it is quite a treat.

While this enormous exhibition of 200 rare manuscripts and books is immeasurably enhanced and literally enlarged by the online exhibition, it is the rare chance to compare Islamic and Judaic manuscripts side by side that makes the exhibition so special. Curiously, the Christian works are for some reason not nearly as interesting from a visual point of view. The curators and advisors: H. George Fletcher, Edward Kasinec, F. E. Peters, Patrick J. Ryan, S.J., Priscilla Soucek, Bishop Anoushavan Tanielian, Michael Terry, David Wachtel have done a splendid job of juxtaposing works in a series of sections that delineate the exhibition’s themes: Monotheism, Abraham, Revelation, Scriptures, The Commentaries, Spreading the Word, Private Prayer, Public Worship. The premise of the show clearly was to find shared approaches to religion and religious life rather than delineate the often murderous clashes between the big three. This is also reflected in the principle sponsorship by the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (philanthropic giving) and The Coexist Foundation, whose name sums up its goals for the three Abrahamic faiths.

Not surprisingly we see a lot of Abraham in this exhibit. A 1782 ketubah from Nizza Monferrato, Italy prominently displays the subject of the Akeidah opposite a Jacob’s Ladder, reflecting the fact that the groom’s name was Abraham Jacob. The artist helpfully identifies the site of the Akeidah as Har HaMoriah as well as providing a little castle directly under the Jacob’s Ladder appropriately titled Beis El. What lends special interest to this Akeidah image is that it is taken from a well-known 1544 painting by the Venetian master Titian. While the town of Nizza Monferrato in the Piedmont region is quite distant from Venice, nonetheless there must have been copybooks circulating among Jewish artists depicting famous images with Jewish subject matter, including works of non-Jews. It apparently didn’t concern the artist that Isaac is depicted as a child in the Christian tradition. What mattered was that his customer understood the content of the famous image.

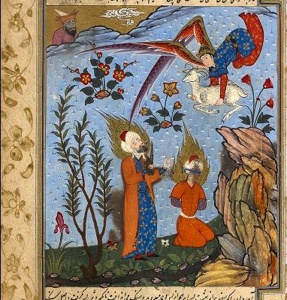

This is brilliantly contrasted with a page from the beautiful Tales of the Prophets by Ishaq ibn Ibrahim al-Nishapuri from Iran in 1577. His Akeidah features Ibrahim preparing to sacrifice his son Isma’il (actually the Koran does not specify the name of Abraham’s son) who is not only bound but blindfolded, quite ready to be executed. Both Ibrahim and Isma’il have fiery halos, typical of all prophets in Islamic art and are approached by a smiling angel bearing a white ram as substitute sacrifice. In the Koran once Abraham places his son ready to be sacrificed God immediately “ransomed him with a momentous sacrifice,” i.e. a fine ram, here being presented by the angel. In the upper left we see a man mysteriously peering over the hill watching. The scene seems filled with magic by its bright colors and florid decoration and yet there is a terrible seriousness evidenced by the bound Isma’il. The crooked angel wings, also typical of Persian art, add to the tension and composition.

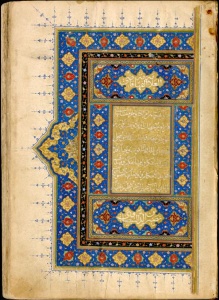

The exhibition is filled with fascinating works that explore all aspects of religious life. There are illuminated Latin Gospels from Brittany, dated sometime before 917, that show the Christian apostles with symbolic beast heads, the artist evidently uncomfortable depicting them with real human heads. One is of course reminded of the Bird’s Head Haggadah where all the humans in the biblical illuminations have bird’s heads. There is an illuminated ‘New Testament’ from 1548 in both Latin and Ethiopic, the language of the Coptic Christians in Ethiopia. The commentary on the Qur’an of al Baydawi of 1569 is beautifully illuminated in gold and lapus lazui and may have been made for Sultan Sulayman (1520-1566) who built the current walls around Jerusalem. Numerous sumptuously illuminated Qur’ans are displayed with commentaries, one with an interlinear Persian translation that points to an early outreach effort to Persians who could not read Arabic.

The Book of Revelation from Germany or the Netherlands around 1465 is a heavily illustrated “block book” (an early form of mechanical printing) that features an abbreviated text and many pictures intended to be used to teach illiterate individuals with the guidance of a more knowledgeable teacher. Perhaps most surprising was an illustrated mishnah that delineated various aspects of the Shabbos boundary and the laws of eruv within a town. While the illustrations are annotated in Hebrew, it was made for Christians to study Jewish law.

Images of Moses are contrasted as we see an illuminated Qur’an from 1580 Iran that shows the angel Gabriel acting as an intermediary between God and Moses as he is receiving the Law. What is especially interesting is that two faces have been inexplicitly defaced; both Gabriel and an anonymous figure in the foreground have had their faces cut out. Nearby are many other examples of Islamic art in which the face of the Prophet Mohammed are either left blank, covered with a veil or reduced to a glowing orb, all aspects of the Islamic prohibition on depicting their Prophet.

Moses is more than well represented in many Judaic works, not the least of is the Hamburg Haggadah, handwritten and illuminated by Ya’akov ben Yehudah Leyb in 1731. Part of the revival of handwritten manuscripts in the 18th century, this work features an elaborate title page and no less than 14 illustrated pages, all hand painted versions of the standard edition copper engraved images. On the page of Dai’ainu the representation of the verse “All that the Lord has decreed, we will undertake to do” is particularly revealing. The point of view is from within the Israelite camp. Moses is seen in the distance atop a little hill surrounded by a fence. We see Aaron at the base of the hill praising Moses as the prophet receives two tablets from a sun burst in the sky. All kinds of tents surround them and in the foreground the Jews, all in contemporary 18th century dress, gesture animatedly as they discuss the obligation just accepted. It is a beautiful example of the moment of Revelation concretized in everyday life.

There are many other works in this exhibition not to be missed including a Masoratic Bible from 1742 featuring a title page with 8 illustrations of Parting the Red Sea, the Revelation at Sinai, Joshua Stopping the Sun, David Playing his Harp, Solomon’s Judgment, Daniel in the Lion’s Den, Ezekiel’s Vision of the Valley of Dry Bones, Esther Before Ahasuerus. Also there is a Tekhines (special women’s prayers in Yiddish) from 1749, an amulet writer’s manual, a 14th century Askenazic Machzor and finally an elaborately illustrated Montalto Megillas Esther scroll (1686) with 7 panels that tell the entire story of Purim.

Wandering through the Three Faiths exhibition and taking in the riches of illuminated books and manuscripts one realizes how much Judaism, Islam and Christianity actually share in their love of sacred texts. While Muslims only started printing the Qur’an in the 19th century, nonetheless all three faiths continue to create hand made manuscripts. With all this in mind and surrounded by such beauty, we can well appreciate the maxim that regardless of how much we may disagree with other religions, we can simultaneously say that there is much wisdom, and I might add, beauty, amongst the nations. As Rav Kook said in Orot (p 152):

God was charitable towards His world by not endowing all talents in one place, nor with one person, nor with one nation, nor with one country, nor with one generation, nor with one world. But the talents are diffused. The necessity of seeking perfection, which is the most important force that acts on us, causes us to seek an exalted unity that is bound to come for the world. In that day will the Lord be one, and His name one.

Three Faiths at the Public Library

Fifth Avenue & 42nd Street

Exhibitions.nypl.org/threefaiths