Way to Heaven by Juan Mayorga

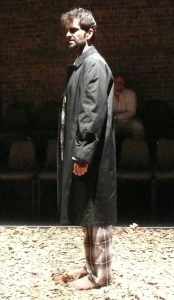

An unshaven man stumbles on stage, clad in a raincoat covering his pajamas. He is barefoot and shuffles among the dried leaves that litter the stage area, a long rectangle set between the audience on either side. It is a most intimate performance area, uncomfortably so. He tells us he was a Red Cross representative, stationed in the Berlin suburb of Wansee, sent to inspect a civilian internment camp in Nazi Germany.

It was during the war and he is now guilt ridden, confused and sleepless. A tortured soul remembering what it was like to play-act to do his job, unaware he was but a manipulated audience himself. He describes the entire visit and the episode unfolds before us. He cannot sleep.

Next, boys play with a top and quarrel, a couple argue over a gift, each actor perfecting their lines, cueing each other to get the dialogue right. We notice they all wear a yellow star. The young woman complains of constantly hearing trains in the night.

Then the little girl enters holding her doll. She talks to her doll telling him not to be afraid and sings a song. A haunting “Ani ma’amin.” She sings “I believe…”

The Nazi commandant strides on stage; confident, charming, understanding, his evil arrogance is barely masked by his civilized and rational demeanor.

Finally, Gottfried is brought in and sits before the Commandant. He is a prisoner, powerless to resist the orders of his captor. He must become an actor, learn his lines and collaborate to give the impression of a benign internment camp. His play-acting seeks to convince that conditions are relatively good and, considering the war, humane. As for the ramp from the railway station to the infirmary, well, everyone just calls it the “way to heaven.” The play has begun.

Way to Heaven by Spanish playwright Juan Mayorga currently playing a limited New York run from May 7 through May 24 at Teatro Circulo (64 East 4th Street) explores the terrible phenomenon of Jewish complicity in covering up the reality of the Holocaust. It is based on the compulsory acting that played out in the “model camp” of Theresienstadt, located near Prague. The play is a historical amalgam, combining aspects of the infamous show camp and the famous July 1944 Red Cross visit to inspect the camp and its subsequent approval by the Red Cross. This awesome “dress rehearsal” is played out in the shadow of the Nazi death machine evoked by the trains that arrive promptly at 6am every morning and the ever-present ramp leading to the death chambers and crematorium. As the play makes relentlessly clear the façade of normalcy; children playing, a balloon seller, a mid-day meal and the petty drama of young lovers all serve to mask the grim reality of what was really a transit labor camp on the way to Auschwitz. Starvation and disease was the norm at Theresienstadt even though the camp was lauded by the Nazis as the safe haven for the Jewish cultural elite of Germany, Czechoslovakia and Austria. Indeed there was an amazing amount of art, music and theater that inmates produced before being shipped to their deaths in the East. Hence the tragic irony played out in Way to Heaven.

The director of the American production (it has been produced in London, Paris, Madrid and Buenos Aires), Matthew Earnest creates a masterful entrapment of the audience, slowly drawing them into the inescapable web of compromise with the use of minimal sets and highly dramatic lighting, allowing the accomplished actors free reign to plumb the depths of each character. Regardless of their lines they are terrified mortals, desperately trying to act scripted parts to save their lives. There is seldom a moment in which a double entendre doesn’t reveal a harrowing truth beneath. Each of the principle characters; Mark Farr as Gottfried, Shawn Parr as the Red Cross Inspector, Francisco Reyes as the Commandant and Samantha Rahn as the little girl all put in riveting performances.

The play effectively moves backwards in time, bringing us along for the ride, starting with the Red Cross inspector’s tortured and guilty memory monologue. While his memory torments him, his recounting troubles us because he has been effectively fooled by the much too convincing acting of the Jews. Indeed in his memory all seemed normal. Why were these Jews so good at acting as if nothing terrible was happening in this “civilian internment camp?” Next we are plunged into the feverish cacophony of inmate rehearsals, repeating lines, trying to get it right with their mechanical readings of dialogue for the sake of the Red Cross.

The Nazi Commandant attempts to beguile us with his assurances of European civilization, the books he has in his library, how he distains war and how once it is all over we will all speak one language and celebrate one culture. His monologue constantly slips between past and present, chilling our confidence in the distance of the past horrors. Suddenly all the lights go out and in the pitch-blackness the Nazi asserts that all of the killing camps are gone now, “There’s none of it left now, but they’re still here. All of them every single one.” The ghosts of the murdered Jews remain because, “Every train in Europe terminates here.”

Further into the past we are plunged into the complex and tortured relationship between Gershom Gottfried, the “Mayor” of the Jews, and the Commandant who is both the author and director of the little piece of theater that will convince the Red Cross that there is no mistreatment of the prisoners. Gottfried’s role is to make sure everyone acts his or her part exactly like the script says, that they understand that their lives depend upon their performance. Gottfried says the people want to know what to expect. The Commandant answers, “Focus on one thought, Gottfried. ‘I’m not on that train. As long as I’m here, I’m not on that train.’” The play-acting becomes instantly clear, their performance is a bargain with the devil himself.

Gottfried is ordered that one scene is too crowded, “Cut them down to a hundred.” Take them to the “infirmary,” that closed shed at the top of the long ramp, at the end of the “way to heaven.” Gottfried balks, he can’t choose which of his fellow Jews will be condemned. He rebels and spits out, “What if we refuse?… [what if] He arrives and there’s no one there… Or we tell him the truth…” The Commandant calmly reminds Gottfried that the Red Cross man may not understand the gesture or the symbol. Jewish rebellion would hardly make an impact and after all would only result in more death.

Sitting so close to the actors, finally understanding their dilemma, understanding that Gottfried and his Jews have no choice, understanding that no one wants to assure their own death, I still ask myself, what would I do? What would I do?

Now the Commandant is alone, musing about the loneliness of the actor, the futility of theater itself. He rants against the little girl with the doll, recalling that in fact she did call out, send a signal of distress to the Red Cross inspector. “I hope he doesn’t mention it in his report.” With this we realize that the world really didn’t want to see, didn’t want to hear of the brutal murder of millions of Jews.

Finally Juan Mayorga’s stunning play brings it all home. Gottfried and his Jews resume practicing their parts, reassuring his fellow actors, “we’ve all had to pretend some time, haven’t we?” The little girl with her doll enters and is comforted by Gottfried. “If you do it well, we’ll see Mummy again. She’ll come on one of those trains. If we do what they ask us… We’ll do it as many times as we have to, until Mummy comes back.” She softly sings her haunting song again. “Ani ma’amin.” Yes, I believe, I believe with a perfect faith.

Way to Heaven by Juan Mayorga

Teatro Circulo

65 East 4th Street, NY, NY

waytoheaventheplay.com