Sarah’s Miscalculation

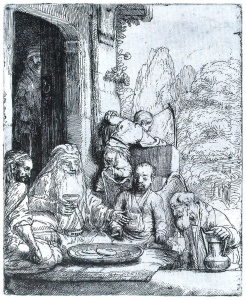

Rembrandt’s etching, Abraham Entertaining the Angels is a pristine jewel of Biblical narrative. The artist depicts the exact moment the story reveals its true meaning. The guests have been comfortably seated and served refreshments by Abraham himself, shown humbly waiting on them in the lower right corner. His head is lowered in rapt attention as the majestic visitor in the center begins to speak. Sarah is listening carefully, just visible in the shadows of the doorway in the upper left. Hanging on every word, all are poised to hear the astounding prophecy of “and Sarah your wife shall have a son!” (Genesis 18:10). But, wait a minute. Who is the youthful figure in the precise center of the image? He is ignoring Sarah and Abraham and the visitors, leaning over the doorstep ledge shooting a bow and arrow. It can only be Ishmael. What is he doing here? Nowhere in this section of the Torah text is he mentioned. Likewise in the Midrashim he is absent, except for a passing reference by Rashi in the preceding line, “and gave it (the calf) to a young man [Ishmael], and he hurried to prepare it.” But what does Ishmael have to do with this scene? What was Rembrandt thinking?

Abraham Entertaining the Angels was created in 1656 by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669), a year that marked a devastating personal financial crisis for the aging artist. Three years earlier his creditors began to hound him ceaselessly about a 14 year old debt incurred by the purchase of a new home. Finally he was forced to submit to a voluntary sale of all his possessions in his home in what is called “cessio bonorun,” similar to bankruptcy declared to satisfy his creditors. In July 1656 they conducted a full inventory of the contents of his house and in 1657 the contents were sold off at a two month long auction. Soon thereafter his son Titus and his mistress Hendrickje formed a company whose sole purpose was to protect the artist from creditors and ensure his survival. Rembrandt was not allowed to own his own paintings and was forced to subsist on funds dolled out by his own family.

Irrespective of the shame and personal anxiety, Rembrandt’s enormous creative output continued unabated. During this time his paintings on Jewish themes are among his greatest masterpieces: Bathsheba (1654, Louvre), Joseph Accused by Potiphar’s Wife (1655, National Gallery, Washington, DC), Jacob Blessing Joseph’s Sons, (1656, Cassel, Gemaeldegalerie) and Moses with the Tablets of the Law (1659, Berlin, Gemaeldegalerie) as well as at least ten portraits of Jews. One theme that seems to run through many of these works at this time is the importance of domestic relationships. It is as if he was especially drawn to the Torah’s narratives of familial complexity.

Rembrandt’s relationship with the Amsterdam Jewish community was always an important factor in his life, but at this time his relationship with Rabbi Menasseh ben Israel (1604-1657) becomes especially dominant. In 1655 he was commissioned to illustrate the rabbi’s Piedra Glorioso (The Glorious Stone). It was to be “the total history of the Hebrew people, until the end of time and the time of the Messiah.” The book centers on Menasseh’s messianic interpretation of a passage in Daniel 2:31-36, the vision of the shattered statue of Nebuchadnezzar. Rembrandt illustrated the smashed statue, the stone that Jacob rested on and David slaying Goliath with a stone, all considered to be the same stone. Finally his fourth image was a depiction of Daniel’s vision in 7:3-28 of the four beasts, the four kingdoms and the final ascent of the messiah. It is obvious that in spite of all of Rembrandt’s deepening personal difficulties he remained as deeply engaged in the intricacies of Jewish though and narrative.

In Abraham Entertaining the Angels Rembrandt utilized the subtleties available in the etching process to fully explore this complex narrative. By varying the darkness and thickness of the lines etched into the copper plate, increasing shadow with different directions of crosshatching and finely attuning delicate versus bold line the artist fleshed out this scene as a narrative that occurs over time instead of a picture of one instant. The attentive Abraham is depicted in relatively few simple lines, much like the Ishmael figure. In contrast the winged angel next to him, surely sent to comfort him, is pensive and half cast in shadow. Opposite him in the lower left corner is an angel in sharp profile, drawn in dark harsh lines, his hand in a fist poised to carry out his mission to destroy Sodom.

The greatest contrast occurs between Sarah, plunged in the deep shadows of the doorway, and the central angel brightly lit seated right in front of her. His face and stark white beard are delicately delineated as he gestures forward to Abraham, into their future. Thus the narrative emerges from upper left to lower right; from the darkness of Sarah’s childlessness, through the brightness of a miracle to the fulfillment of God’s promise to Abraham. Nonetheless, the question remains to Rembrandt, what is Ishmael doing here?

In order to understand we have to go back to the very beginning of the story of Abraham and Sarah. The Torah introduces us to them at the end of chapter 11, verse 29; “and Abram and Nahor took themselves wives; the name of Abram’s wife was Sarai… and Sarai was barren, she had no child.” In the repetition the Torah emphasizes that Sarai was barren by definition. And then within eight lines the Torah tells us “Hashem appeared to Abram and said, “To your offspring I will give this land” (12:7). Therefore the dramatic scene is set, how can Abraham have children whom God promises to inherit the land when his wife is barren?

Sarah understands the problem quite well and, after living together for ten years, she decided to do something about it. She took her maidservant, Hagar, and “gave her to Abram, her husband, to him as a wife. He consorted with Hagar and she conceived…” (16:3-4). While this should have solved the problem, it didn’t. Sarah hadn’t counted on Hagar’s corrosive jealousy and competitive nature once she had been intimate with Abraham. Their relationship was rocky from the outset and only deteriorated more once Ishmael had grown into a wild and mocking youth. Certain that Ishmael was not fit to inherit the legacy of Abraham’s God, Sarah was out of options. This impasse was what prompted God Himself to intervene and send angels to tell her and Abraham that a miracle would happen, circumventing nature itself; they would be able to have a child together.

Ishmael is seen in the very center of Rembrandt’s etching because he is the central problem that the angels have come to solve. Sarah was mistaken, the future would not be fulfilled by Hagar’s child, no, God would decide that only a child of Sarah and Abraham would carry forward the Abrahamic covenant. Ishmael’s violence with his bow and arrow is being pushed aside, bypassed by the narrative that flows between Sarah, the luminous angel and the aged Abraham. And now we can see the narrative genius of Rembrandt, the insight of his aesthetic choices in his little masterpiece etching, Abraham Entertaining the Angels. The future was with Isaac.