The Medieval Haggadah: Art, Narrative & Religious Imagination

The Golden Haggadah was created in Catalonia, Spain sometime around 1320. So named because all the illustrations are placed against a patterned gold-leaf background, it is a ritual object of incredible luxury and expense. In light of Marc Michael Epstein’s analysis found in his recent book The Medieval Haggadah, this tiny masterpiece of Jewish art easily ranks among other towering works of complex narration including Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel in Padua and Michelangelo’s Sistine ceiling in Rome. With his exhaustive analysis in hand we can now “read” it with the same intense multifaceted interpretation as accorded scripture itself.

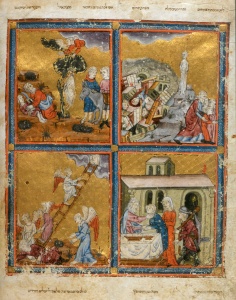

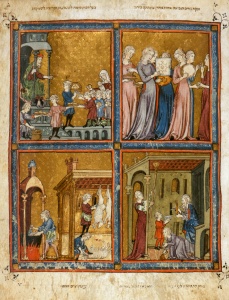

The text of the Haggadah is prefaced by 8 pages of double-sided illuminations, each side containing 4 narrative scenes. Since the 56 illuminations frequently depict more than one aspect of a biblical narrative, the overall scope of the illuminations is vast. The first 27 scenes are from Genesis starting with Adam naming the animals, the next 26 portray the Exodus itself and the final 3 scenes depict medieval domestic Passover scenes.

There is of course extensive literature concerning this Haggadah, much of which focuses on its context in “conventions of Christian visual culture” and use of Christian motifs to the detriment of Jewish meanings and iconography. Epstein challenges these views and sees “an aesthetic shared by Jews and Christians in early 14th century Catalonia” and demands an overwhelmingly Jewish orientation that consistently transforms Christian motifs into Jewish meanings.

Superficially, the selection of these particular biblical stories has no explicit relationship to the Haggadah text that follows, other than in the most general sense that the stories of Genesis lead up to the Exodus. Epstein therefore insists that more substantive significance will be revealed if we see the illuminations in the light of two medieval exegetical models. “The narrative sequence of the biblical text is expressed via the conventional progression of scenes, corresponding to pshat, contextual exegesis, in medieval biblical commentary. But the moral, theological, and political themes that were important to the authorship and that they wanted to stress are found in the chiasmic [diagonal across the page or pages] readings, corresponding to drash, homiletic exegesis.” What is especially fascinating is that Epstein is linking different sequences of seeing to specific conceptual exegetical models. To complicate matters, these links may be positive echoes or negative contrasts of meaning. This may very well be a totally unique procedure in the analysis of visual art.

Epstein organizes the 56 illuminations on three levels: first the group of 4 found on one page, secondly the group of 8 seen on two facing pages and finally patterns he discerns throughout all the illuminations. In what he identifies as the Bifolium 2 (two pages facing one another), the narrative literally proceeds from upper right to upper left, then back down to lower right and finally to lower left, exactly as Hebrew is read. The subjects chronologically unfold as: Destruction of Sodom, Akeidah, Jacob Steals Esav’s Blessing, and Jacob’s Ladder. On the facing page we see Jacob Wrestling with the Angel, Joseph’s Dream, Joseph Sent to his Brothers and Joseph Encounters the Angel in the same zigzag pattern.

Epstein immediately observes the connection between the diagonal of Jacob’s Ladder that continues up through the ruins of Sodom. This chiasmic (diagonal) link contrasts the destruction of the evil city of Sodom with the eventual construction of the holy city of Jerusalem at the site of Jacob’s ladder. In a divergent manner the Akeidah operates as a typology (ma’aseh ‘avot siman le-banim–the events of forefathers foretell the events of later generations) to Jacob’s stolen blessing, each confirming the Divine choice of which son was to carry forward the history of the Jewish people. Suddenly a simple Biblical progression of Lot, Abraham, Isaac to Jacob develops into a nuanced complex commentary about retribution, holiness and inherited divine mission.

Further nuances emerge as Epstein observes that in this page delineating the early Israelite family tree, the right side of each image is dominated by ‘negative’ figures. Lot hastens off with his daughters who will produce Amon and Moab; Ishmael, forefather of the Arab peoples, stands next to the donkey at the Akeida, Esav, forefather of Rome (i.e. Christianity) rushes in on the right and finally at Jacob’s Ladder we see on the right the angel of Esav preparing to attack the sleeping Jacob.

The repetitive flow of angels across the two facing pages yields more insights into the unfolding narrative. On the left-hand page Jacob Wrestling with the Angel is diagonally mirrored by the (non-textual) angel Gabriel guiding Joseph; compositionally 2 figures on the right are placed in contrast to a group of 6 figures on the left. This again echoes “ma’aseh ‘avot siman le-banim” to show that just as Jacob encountered an angel at a crucial juncture, so too his son Joseph’s fateful encounter with his brothers was precipitated by the direction of an angel.

This kind of interpretative analysis that Epstein offers liberates the images from merely illustrating biblical scenes. By virtue of diagonal visual relationships and repetitive motifs the artist creates a homiletical commentary that simultaneously relates back to the Haggadah text; “Originally our ancestor were… but Jacob and his children went down to Egypt” and elucidates free-standing insights on its own. The visual has become an equal partner with the ritual text as a reflection of scriptural complexity. What is perhaps most valuable in this kind of reading is that, by its very nature, it is only one of multiple possible meanings and its methodology can be applied wherever there are multiple images in juxtaposition to one another.

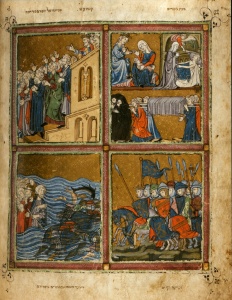

The last set of facing pages of the Golden Haggadah presents us with not only the climax of the Haggadah’s visual narrative but also a totally unexpected insight into a major underlying theme. The right-hand page begins with the Death of the First Born, proceeds to the Children of Israel Departing; down to the lower right the Egyptian horsemen pursue and finally the Egyptians are drowned in the Sea. The facing page begins with Miriam’s Song and then morphs into 3 scenes of contemporary medieval Jewish life; handing out Kimcha d’Pischa (literally matzoh dough), on the lower right cleaning house and finally slaughtering the Passover lamb.

Epstein reflects upon the unusually large number of women found in the Golden Haggadah. Over the course of 56 narrative panels there are “no fewer than 46 prominent depictions of women” not the least of which are the women depicted in the Song of Miriam, all of whom tower over the surrounding panels and are proportionally the largest figures in the entire manuscript. Beyond this startling observation that had gone unnoticed by earlier scholars, is the fact that this number of women are more than found in any other Spanish Haggadah. Furthermore they are found in scenes fundamental to the halachically mandated narrative, “to tell about the Exodus from Egypt,” as well as more peripheral narrative panels. Considering the illuminations from Genesis and Exodus the figures of Eve, Sarah, Lot’s wife and daughters, Rebecca, Potiphar’s wife, the midwives, and Miriam are not at all surprising. But then we notice “corroborative figures” whose presence has no compelling presence such as prominence of Noah’s wife and daughters in the scene of Noah and the Ark. Finally there are “incidental figures,” women who seem to be narratively no more than “extras,” such as Egyptian women afflicted with lice, female mourners over the dead first born and Israelite women at the Exodus and at the Sea of Reeds. Epstein believes the choice to include many scenes from Genesis, a book with many important women characters, was a conscious choice to increase and prioritize women’s roles.

Miriam’s Song is not narratively necessary (Moses’ song is textually recorded complete while Miriam’s is a one-liner) nor is it always found in other Haggadot. But here it is accorded disproportionate prominence. It is not only visually dominant; it also forms the crucial transition from the Exodus narrative to contemporary medieval reality. They are featured as contextually abstract against the flat golden background, unlike any other figures in the Haggadah, “hence timeless.” I might add that the composition of these seven women itself is easily the most elegant, balanced and graceful of all the images.

Its companion panels are no less revealing. The principle mourners in the Death of the First Born are all women: including the woman in a pieta-like pose with a dead child in her lap, Queen of Egypt mourning and finally the black-clad women leading the funeral procession, all non-textual. Further along Epstein notices that the departing Israelites are led not by Moses, but by two women, one of whom is carrying an infant. Finally on that page the ‘Drowning Egyptian army in the Red Sea’ is contextualized by the fleeing Israelites, here led by a woman holding an infant accompanied by a man with a child on his shoulders. The ubiquitous presence of women is impossible to ignore.

Crossing over to contemporary medieval reality, the head of the household is seen as handing out matzah and charoset to a woman who has six children, reflecting the midrashic account of Israelite women who miraculously brought forth 6 children at each birthing. Not satisfied with the received notion of fecundity, the artist gave her an addition infant in her arms, pointing to a future age of even greater Jewish fruitfulness. In keeping with this kind of reading, Epstein believes that the last panel in the lower left showing Passover preparations alludes to the restored Passover sacrifice in messianic times. This is because the animal being prepared is in fact a lamb, forbidden for consumption on Passover after the destruction of the Temple, but permissible in messianic times.

It is in light of the proliferation of women and images dealing with infants and children that Epstein believes the Golden Haggadah may very well have been created initially for a woman, and perhaps even a woman who suffered the loss of a child. This is of course a matter of scholarly speculation. But what is not speculation is the rigorous and dynamically creative methodology Epstein has introduced into the analysis of this towering masterpiece, convincingly bringing it alive today. Additionally, I believe that the most exciting contribution he has made with this kind of complex, non-linear relational visual thinking is its possible utilization to the creation of contemporary works of Jewish art. It is a way of thinking and seeing perfect for our time.