Menorahs in Jewish Art

Why is the menorah such a powerful and long-lasting symbol of the Jewish people? After all, its lure ostensibly originates in a relatively minor rabbinic festival, Hanukah. No disrespect intended, but how can Hanukah compare to the great pilgrimage festivals, Passover, Shavous and Succos or the Days of Awe with Rosh Hashannah and Yom Kippur?

Of course it is not the Hanukah menorah that captivates us, rather it is the Temple menorah that carries such an awesome power. Originating in the Torah commandment in Exodus 25:31 “you shall make me a menorah of pure gold…” Rashi explains that so wondrous and complex was the menorah that is was finally fashioned with a miracle; “throw a kikar of gold into the fire and it will be made by itself.”

The earliest image of the menorah we have is bronze coin minted by Mattathias Antigone in 40 BCE. Not much to speak of artistically, it nonetheless shows how much the last of the Hasmonean rulers thought of a symbol that was ultimately associated with them. Tragically the next time we see the menorah is on the Arch of Titus, built in 81 CE in Rome to commemorate the victory over the Jewish revolt and the destruction of the Temple (Jewish Press, Jewish Arts, 7/25/07). It is the golden prize the conquering Romans most associated with the stiff-necked Jewish people. Little could they imagine we would also proudly claim this as our national symbol. Throughout late antiquity the menorah was the elemental symbol of the Jewish people.

“The dominating symbol of Jewish funerary art” (Gabrielle Sed-Rajna) in antiquity was the menorah. In the necropolis of Beth Shearim containing the graves of Judah HaNassi, Rabbi Gamaliel, Rabbi Simeon and Rabbi Hanina the menorah is found in graffiti, in many sarcophagus carvings and on wall paintings. Similarly in the Roman catacombs of the Villa Torlonia dating from the 3rd to 4th century the menorah is prevalent as a Jewish symbol. What is fascinating is the abundant use of this symbol, evidently as an eschatological sign in conjunction with an imagined Third Temple facade, in an unseen secret underground graveyard.

Not surprisingly the earliest example of Jewish narrative art, the synagogue murals at Dura Europos (245 CE), finds the menorah on its Torah niche. The crowning façade of the Torah niche features a large menorah with seven straight arms radiating from a massive base, quite unlike any menorah image of its time. The overall composition, menorah on the left, Temple façade in the center and Akeida or ram’s horn on the right is seen in many synagogue mosaic floors for the next 300 years. While because of its provincial location Dura could not have been the original model (Dr. Evelyn Cohen) it is nonetheless the earliest example of this persistent motif. Many scholars see this image, almost always placed near the most sacred part of the synagogue where the Torah would be kept, as an intense visual expression of the yearning for the Third Temple and the end of days.

It is seen in many variations in the mosaic floors of Hammath Tiberias, Beth Alpha, Susiya, and at Beth Shean, among other ancient synagogues. At Beth Shean (6th century CE) the motif is expanded to include two giant menorahs flanking a representation of the Temple showing the curtained Holy of Holies. Most significantly it is the menorahs that dominate the image, functioning as guardians of the Holy. It would seem that in the 500 years subsequent to the destruction of the Temple Jewish pictorial art continued to yearn for, indeed demand, its restoration. Always the menorah was the symbolic vehicle of such faith.

These same impulses are found in medieval manuscript illuminations, especially early illuminated bibles. Perhaps one of the most elegant is the Cervera Bible (1300) from the Catalonian region in Spain. This bible with a masoretic text was illuminated by one Joseph ha-Zarefati (the Frenchman) and contains on folio 316v a full-page miniature of Zechariah’s vision of the menorah. It is flanked by two olive trees that produce the oil that fuels the golden Temple menorah. According to Bezalel Narkiss this “menorah symbolizes the restored Jewish state, while the olive trees and their sprouts represent the “two anointed ones,” Zerubbabel of Davidic descent and Joshua the high priest.” In a remarkable combination of imagery from the Torah’s description of the Temple menorah and Zechariah’s (Chapter 4) vision, this image manages to span millennia from the beginning to the end of Jewish history. As the haftarah reading of the Shabbos of Chanukah it is especially apt exhorting Jews to rebuild the Temple and restore the Jewish state.

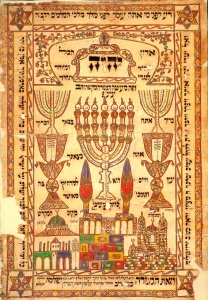

The golden Temple menorah remained a potent symbol throughout the ages, always present in synagogues and Jewish visual representations. A shiviti from the 19th century made by an itinerant Chabad emissary from Hebron, Shneur Zalman Mendelowitz, was designed for use in the home, probably designating the eastern wall of a room in which one would pray, proclaiming “Know before Whom you stand…”

Shiviti HaShem, l’negdi tamid; (I have set Hashem before me always – Psalm 16:8) is read top down and then horizontally. Aside from the odd textural design, curiously the word Shiviti is written very small in the crown above HaShem. Conversely, what is dominant is the verse that proclaims; “This is the workmanship of the menorah hammered gold…” Numbers 8:4 right above the central menorah. Beneath the three fantastic menorahs are depictions of three sites in the Holy Land clearly labeled: the Cave of Machpelah, the place of the Holy Temple and, in the center, the Western Wall. From the nature of the imagery and overall context the strident demands of restoration of earlier centuries have softened into a nostalgic yearning. This dream, tempered by more than 1800 years of waiting, has accepted that national restoration would be in a still distant future. Little could the artist realize that the dream was about to begin to be realized.

Many have said that with the creation of the State of Israel, a real Jewish homeland and nation, we have finally arrived at the “first flowering of our redemption.”

The Knesset Menorah by Benno Elkan (Jewish Press, Jewish Arts 1/16/09) given to the State of Israel by the British people in 1956 goes a long way to become one such expression. Twenty-nine relief panels articulate the belief that the purpose of the history of the Jewish people was to bring us back to our land, back to Jerusalem. All of the images of Jewish history flow counter-intuitively from top down to the center branch and down to the lowest image of the rebuilding of the Jewish homeland. While Elkan’s Knesset Menorah doesn’t actually depict the Third Temple and our final redemption, it funnels all of Jewish history and the return to our land as a prerequisite.

It would seem as if the image of the menorah could not be used for anything but the restoration of our homeland and ultimately the restoration of our Temple. And of course this is how the Temple menorah can become our Hanukah menorah. One branch is added to accommodate the miracle of the oil but the underlying meaning remains the same; we were commanded by God to make a menorah to illuminate our lives with a holy Temple, it was true two thousand years ago and it will be true in a time soon to come.