The Book of Lamentations: Illustrated by Mark Podwal

In 1974 Mark Podwal, noted author, illustrator and physician, created a spare, illustrated Book of Lamentations. This complete English translation is graced with 28 black and white illustrations, or more correctly, reflections, on the tragic text. Podwal maintains Jeremiah’s alphabetical acrostic of each chapter containing 22 sets of lines, reflecting aleph to tav, denoting each English set with the appropriate Hebrew letter. According to Sanhedrin 104a “R. Johanan said: Why were they smitten with an alphabetical dirge? Because they violated the Torah, which was given by means of the alphabet,” representing the tragic reality that the Jews of his time transgressed the Torah from aleph to tav, beginning to end. Eicha!

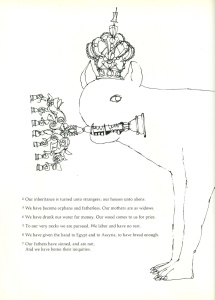

Podwal’s visual reflections here all utilize existing works of art to extend his metaphorical reach. The fifth chapter begins: “Remember, O Lord, what is come upon us. Behold, and see our reproach. Our inheritance is turned over to strangers; our houses unto aliens.”

A vicious beast glares out at us, clasping an 18th century Polish menorah in its teeth and blasphemously wearing a Torah Crown. The midrash comments that “our inheritance” refers to the Temple. In Podwal’s illustration this becomes the ornaments of our synagogues, tragically plundered. And to add insult to injury, the beast is none other than the iconic Capitoline Wolf, a medieval bronze sculpture of the she-wolf who nursed and saved the legendary founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus. This terrifying pagan image represents the cruel Roman conqueror making off with the symbols of our pillaged faith. Eicha!

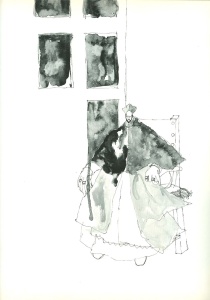

There was perhaps no greater terror in Jewish history than the fanatical Inquisition faced by the Spanish Jews. While their mandate was only for Spanish Christians, the Inquisition especially preyed upon newly converted Jews and Muslims suspected of secretly practicing their old faith. The methods of spying, intimidation and torture led to harsh imprisonment, forced confessions and frequent execution by being burnt at the stake or beheading. The infamous Auto-de-Fe, a public ritual procession of accusation, humiliation and finally execution by burning, as well as all other investigations, were under the administration of the Grand Inquisitor. Torquemada (1483-1498) was the most notorious, especially known for his hatred of the Jews and central role in their expulsion from Spain in 1492. Many more Grand Inquisitors followed him, including Cardinal Don Fernando Nino de Guevara who was painted by El Greco in 1600. Arrayed in his ecclesiastical robes he is the epitome of church power. His black glasses frame a serious and determined face all too accustomed to cruelty.

“Thou hast heard their taunt, O Lord, and all their devices against me. The lips of those that rose up against me, and their muttering against me all the day” (3:61-62).

Podwal’s Inquisitor is overwhelmed by the robes of his office, just like his oversized hands emphasize the extent of his reach into innocent lives. The black windows behind him mask the screams of his victims. Eicha!

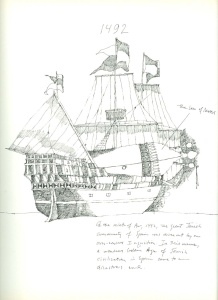

Ships are so often positive symbols of exploration, hope and prosperity that we must adjust our perspective to understand that for 16th century Spanish Jews, they were the tragic means of exile from their homeland. As we recently saw in the frontispiece of the 1553 Ferrara Bible (Jewish Press: June 8), the floundering galleon became the symbol of the Spanish Jews in exile. The passage to exile was defined by the ship, combining its very real hardships with the realization that there would be no return home. While the Ferrara Bible image represents nothing but the pain of loss, Podwal’s ship sees the hope of saving their unique Torah and bringing it to new shores to spread its exceptional learning. Nestled in its foredecks the Sephardi tik naturally fits as the primary passenger in this modern understanding of the tragedy of Spanish Jewry.

“They have heard that I sigh; there is none to comfort me. All my enemies have heard of my trouble and are glad. For Thou have done it. You will bring the day that You have proclaimed. And they shall be like unto me” (1:21). Between image and text there is the hope of a Torah future in spite of the bitter pain of exile and a home destroyed. Eicha!

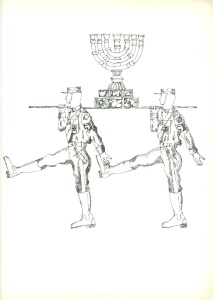

And then there is the subject that seems to transcend time, the Arch of Titus (81 CE). For close to nineteen hundred years no greater image of infamy existed for the Jewish people, the arch itself planted in the heart of Imperial and then Catholic Rome. Its central image of the Golden Menorah, pillaged from the Temple and paraded through the Roman forum, existed as an open wound in the Jewish soul.

“The adversary has spread out his hand upon all her treasures, for she has seen that the heathen have entered into her sanctuary, concerning whom You did command that they should not enter your congregation” (1:10).

Much to our horror, the infamy of our punishment was indeed matched in the Holocaust. Jeremiah’s dirge addresses that tragedy equally well and Podwal’s image shockingly links the two events as storm troopers march in goose-step carrying the same Temple menorah from the Arch of Titus. Here the image reverberates with tragedy for while the six million martyrs came from all walks of Jewish life, especially decimated were the countless pious communities of Eastern Europe, surely themselves a Temple ornament to in the larger House of Yisroel. Eicha!

Mark Podwal’s Lamentations weave ancient sorrow with Jewish history to bring Jeremiah’s dirge into contemporary consciousness. His remarkable images will haunt us for years to come.

The Book of Lamentations: Illustrated by Mark Podwal

The National Council on Art in Jewish Life, New York 1974

1 Comments

backlink checker ahrefs

I don’t normally comment but I gotta state thanks for the post on this amazing one : D.