Robert Kirschbaum: Small Paintings from The Akedah Series

Our encounters with the Divine are precious moments of personal religiosity. We believe that when we pray we are speaking directly to God and at that moment we are in the Divine presence. And yet we are seldom conscious of the awe and fear we should also feel.

At the core of Jewish monotheism is terror. Its source is in Chapter 22 of Genesis, the story known as the Binding of Isaac. God‘s faithful servant, Abraham, has been ordered to take his beloved 37-year-old son (a child he had at the miraculous age of 100) and offer him as a sacrifice. After a three-day journey Abraham has bound his son Isaac, placed him on the altar and has grasped the knife to execute God’s awful command. At the very last moment an angel calls out, “Abraham, Abraham… do not stretch out your hand against the lad nor do anything to him.”

Abraham’s blind obedience to God brutally suppressed his innate kindness and love for his son, as well as abandoning his expectation to fulfill God’s original promise to “make of you a great nation.” The sudden transformation of Abraham from loving father to child-slaughterer to father again was no less wrenching for Isaac who was ready to be a victim of his own father, only to be replaced by a miraculously produced ram. The shared near-death experience creates the terror of not knowing what an all-powerful and yet inscrutable God will command next. One is simply rendered helpless and terrified.

Nonetheless, the tragedy is averted and Abraham has successfully completed God’s final test of the depth of his faith. Abraham and Isaac never speak to each other again. Isaac marries and produces his sons Jacob and Esau. This narrative that effectively concludes Abraham’s dialogue with God is Isaac’s terrifying introduction to the God he will call his own and pass on to the Children of Israel. This God, transcendent and ultimately unknowable, is known as Pachad Yitzhak, the Fear of Isaac (Genesis 31:42). This encounter between God and man is the subject of Robert Kirschbaum’s Akedah Series.

The ten paintings currently on view at the Three Rivers Community College in Norwich, CT are mixed media on paper, all 9” x 8” and created in 2008. While modest in scale Kirschbaum’s utilization of abstract elements effectively narrates the biblical text of the Binding of Isaac while taking it to a surprising and dramatically creative conclusion.

Each of the 10 images he creates repeats a scene in which a limited number of elements operate. A band approximately one-fifth of the page wide flows across the top and bottom, repetitive and yet with enough variation to engender visual interest. Dividing the pages into three registers with the center panel always the largest allows the artist to introduce rectangular shapes that grow, multiply, morph into 10 floating cubes, disappear, appear and finally become mysteriously a kind of doorway. Predominately black marks on a white ground set a constant tenor to the series, linking all the images. A very selective introduction of color against the black and white allows it to evoke disproportionate emotional power. Considering the limited color and repeated format, each of the works is surprisingly rich in the range of marks, calligraphy, gestures, shapes and pictorial space brought to bear on this extremely perplexing subject. While not immediately apparent, Kirschbaum is constantly walking the fine line between abstraction and symbolic representation.

Returning to the text one cannot avoid deeply disturbing questions. Why would God ask his beloved servant Abraham to sacrifice the son he had been promised for so many years? How could Abraham have complied without an argument or objection? What were the consequences of this test on Abraham and Isaac; and finally, how does Abraham’s test affect us today?

The merit of Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son is no less than the very foundation of the Jewish relationship to God. While the liberation from Egyptian bondage and the subsequent acceptance of the Law at Mount Sinai are the operative mechanisms of Jewish belief and practice, it is the Binding of Isaac that sets the standards and expectations of faith. In the flowering of Jewish visual arts following the destruction of the Second Temple seen in surviving synagogue mosaics, the Binding of Isaac is the only narrative depicted. As the central motif in the liturgy of Rosh HaShanah and Yom Kippur, it is the central biblical episode that we celebrate and effectively present to God when we ask Him for forgiveness of our sins. We confess our failures to properly keep God’s commandments, bemoan our inadequate merits and repeat over and over again that we only ask God to forgive us and grant us blessing in the year to come in the merit of Abraham’s faith and courage in being willing to sacrifice his son. And even though the sacrifice was halted and never happened, we refer in the liturgy to the “Ashes of Isaac;” the terrifying willingness was equivalent to the act itself. The heart of Jewish faith is deeply rooted in the terror of the Binding of Isaac.

For more than two thousand years religious thinkers have pondered the meaning of the Akedah. Kirschbaum brilliantly suggests a radically different reading of the episode. Through a ten-part process he narrates how the encounter with the Divine in the Akedah leads to a revelation, mystical disintegration and finally a possibility of entrance into another realm.

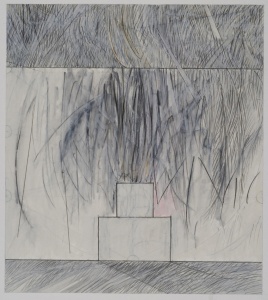

Kirschbaum’s Akedah images are sequentially numbered with gaps in the numbering representing images he has chosen not to exhibit. Akedah #39 begins the narrative showing three ovals floating above the central space as an elemental rectangle emerges from the bottom center of the image. It is the beginning of the construction of the altar built by Abraham in order to slaughter his son. In the flurry of dark marks that come together in the center of the image the first suggestions of encounter appear atop the altar.

In the next painting, #40, the altar is fully formed with a broad base and square top, silhouetted against a brooding sky. Paradoxically for an abstract image, the altar’s depiction is so realistic that it casts a shadow. In the next two paintings the altar, here thought of as the paradigmatic place of meeting between Abraham, Isaac and God, seems to take over the image. Foreboding traces of red and orange reflects the bloodletting commanded.

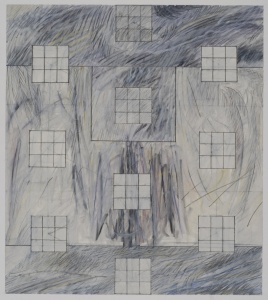

Suddenly the fifth painting is radically different with ten squares appearing in a vaguely familiar regular pattern. Each square is composed of nine smaller squares, the classic nine square grid. According to the artist, it expresses a typical division of sacred space reflecting a realization of Ezekiel’s vision of the Third Temple in additional to the ancient expression the golden rule of balance. For him each is a self-contained universe. Not accidentally the entire design of these floating squares depicts the Ten Sefirot of the Kabbalah.

The standard chart of the Ten Sefirot is a representation of ten aspects of the Divine essence, starting from the top at the Crown, expressing the Ineffable, and emanating downward as it finally connects with the mundane world in the Divine Presence of the Shekhinah. In the world of Kabbalistic mysticism, this is a metaphoric depiction of God’s “body,” itself an inconceivable notion. In Kirschbaum’s depiction it is the fulcrum of the Akedah narrative; the Divine meeting with Abraham and Isaac at the moment of the aborted sacrifice. Blind faith and unquestioning obedience are rewarded by the revelation of the Divine Presence.

The next three paintings are a disintegration, a collapse into frantic, expressive energy, violence and potential chaos. The experience of Divine encounter has been overwhelming, disarming and dangerous. We see in #48 the appearance of another small rectangle at the bottom that quickly evaporates. Finally it appears again in the next to last image, strong and assertive, rising over half the height of the paper with bold black lines and shading to define it. Finally in the last image it has become the portal of an archetypical doorway. The floating ovals have reappeared as if shepherding in this new concept of the encounter with the Divine.

Kirschbaum has taken us along a remarkable road of the Akedah narrative, willfully ignoring the textual details and insisting on the momentous content. What is an encounter with the Divine like? Shattering, terrifying, and yet providing the most complete revelation of the Godhead a human could bear. And its consequences? A doorway, a possibility of another connection that, even if never used, is the reality of a passageway to the supernal. Kirschbaum’s answer to the age-old questions of the Akedah is that the encounter between Abraham, Isaac and God has created the possibility of always being able to reach out to God and find a partner in the relationship between Creator and created.

Kirschbaum’s Akedah Series asserts that we do not have the right to interrogate God’s purposes. Whether it is an awesome test of Abraham or our own struggles of faith in the face of personal disaster, God’s decisions are beyond dispute. Additionally, in terms of the biblical narrative, it is immaterial how this affects Abraham and Isaac as actual people. No; the artist tells us that something else must be ascertained. The meaning is well beyond such mundane concerns. It is about a portal, a portal to the Divine.

The Akedah encounter provides us with a unique opportunity to approach the doorway to the Divine. The decision of whether to just peer into it in awe or to attempt to enter via some kind of mystical speculation is ours to ponder. Whatever our choice; after the Akedah the door is always there. Kirschbaum’s Akedah Series reveals that awesome portal.