Lynn Russell: A Growing Unease

Lynn Russell’s work presents a vexing aesthetic problem. She insists on treading the murky line between photography and painting; between mechanical reproduction and handmade creation. Hardly alone, her quest is in fact one of the major discourses of Modern Art. The early 20th century saw the utilization of commercial typefaces, printed patterns and newspaper clippings in groundbreaking Cubist collages while at the end of the century Pop Art celebrated multimedia and Postmodernism erased the cultural distinction between art and popular culture. All aspects of aesthetic experience, from the banal to the sublime, are now legitimate material for the creation of art. The uniqueness of Russell’s work rests in the fact that she operates in the arena of Jewish meaning, building a legitimate third realm that supersedes the limitations of both photography and painting.

All of the paintings she is currently showing at the Langer Gallery in Flatbush are oil on canvas and share the unique quality of being derived from her own photographs.. The images are transferred onto the canvas and then worked, manipulated, and transformed into oil paintings. The final paintings never possess the photographic feeling of cold documents, a slice of time captured by the camera. Rather the oil painting has extended the sense of time and scope of the original subject, giving resonance and subtlety that causes each to narrate well beyond the photographic image. It is as if Russell is able to simultaneously speak in two voices; the measured eye of a photographer and the sensuous creativity of a painter.

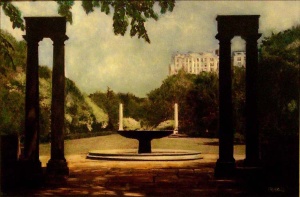

Garden at first seems to capture an iconic image from the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, a bucolic setting of classical columns and fountains in a planned urban garden. The two white columns at the far end of the green are echoed by a pair of double columns silhouetted in the foreground in an extremely balanced, even static composition. The foliage drooping over the top of the image further encloses the view, lending an intimacy to the vista. Looking closer however, another motif emerges. The two distant white columns seem perched on the far edges of the fountain, turning it into a kind of two branched Shabbos candelabra. Now this central image resonates forcefully with the foreground pairs setting up a metaphor for finding a symbol of Shabbos in the everyday. The white apartment building peeking over the distant foliage further enhances this metaphor of Shabbos somehow present, at least by implication, in otherwise innocent landscapes.

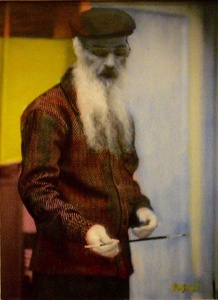

This act of visual transformation occurs again in the seemingly prosaic painting, Artist with Brush. The portrait-like image is characterized by vibrant colors shimmering around the white bearded painter. His heavy jacket and cap tell us that there may not be enough heat in the studio, echoing the frequently difficult circumstances many artists face. His eyes are in shadow, practically accusing the viewer of indifference while the pivotal image of his brush is seen in the extreme foreground. He holds the brush delicately balanced in visual juxtaposition between his two hands. What is being held in the balance? Survival verses creativity, communication verses inspiration? Making art is indeed a balancing act that this painting begins to uncover.

The growing unease of Lynn Russell’s images reflects the paradoxical experience of viewing an image that is clearly derived from a photograph, i.e., from reality, and the end result in oil painting of an unexpected meaning that confounds or questions the initial visual assumptions. The dependence of these paintings on photographs is precisely the aesthetic engine that sets in motion an unmasking of what is apparently real. The “reality” of the photograph is subverted and a more complex meaning is explored in paint.

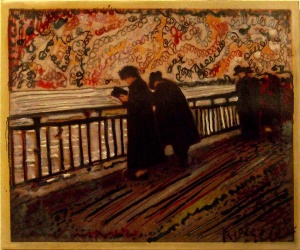

An electric disturbance suddenly fills the air over pious Jews in Tashlich. Poised at the riverside rail five individuals perform the Rosh Hashana ceremony, repeating psalms, supplications and meditations. This photographic image is almost completely effaced by oil paint, creating a new visual entity much in the same way that we hope our sins will be erased, as if swallowed up by the sea, to allow us a hopeful new year. But what does the visual static in the sky symbolize if not the terrible fact that sin cannot be erased, sin sullies creation and in fact that we must live with and overcome the effects of sin. The pollution of the moral atmosphere we create can only dissipate by our repentance and good deeds.

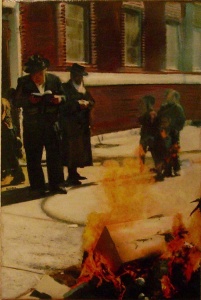

Lynn Russell’s painterly explorations cannot seem to avoid uncovering hidden meanings in the most common of Jewish customs. This may be the case because in the very act of subverting a photographic image new realities are exposed, images that were lurking just beneath the surface now cast a new light on what was once familiar. Be’or Chometz seems at first a documentary snapshot of the day before Passover. Yet a vision of tragedy quickly surfaces. The adults supervising on the left have not noticed that the three children’s faces have become effaced in the atmospheric heat of the fire. The fire itself is ominous as a burning box takes on the shape of the peaked roof of a house, somehow inevitably eliciting the burning of Jewish houses, a fiery echo of the Holocaust. How do we know what portends in these young Jewish lives, how can we know what tragedy lurks.

Photographic reality is limited by what is in front of the photographer. The application of oil paint and imposition of an artist’s vision suddenly upsets the assumed stability of the mundane world. Beneath the calm banality of the visual Lynn Russell uncovers a universe that is ours to shape and experience with a growing unease.

Lynn Russell

Langer Gallery

1079 East 18th Street

Brooklyn, New York