At The Metropolitan Museum

Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675), one of the great masters of the Golden Age of Dutch painting, had nothing to do with the Jews. At least not directly. But I think that his work, shown here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the historical context of the Delft School, actually has a considerable Jewish content that, once discovered, will be seen to be at the core of his creative process.

This exhibition at the Metropolitan, Vermeer and the Delft School, presents fifteen of the 34 surviving paintings of Vermeer in the overall context of many contemporary artists including the celebrated Pieter de Hooch, Carel Fabritius and Emanuel de Witte. Through this approach we are able to see that Vermeer’s work reflected the contemporary artistic interests in light, well defined interior spaces and domestic scenes. We can also see how he took this framework and explored totally unique artistic territory.

Initially, we are introduced to the city of Delft through panoramic views of the city, portraits of important citizens and luxury goods produced there. Delft was at the time a thriving market center dependent upon linen manufacture and beer brewing in addition to ceramic manufacturing of Delftware (distinguished by its luminous blue designs) and luxury tapestry weaving. There was a wealthy ruling class that had generally conservative and sophisticated artistic tastes.

Further along in the exhibition we see the kinds of paintings and objects the good citizens of Delft collected. Typical for the tastes of the time were mythological and biblical scenes, floral arrangements, princely portraits, an anatomy lesson, decorated plates and paintings of church interiors. The eighteen paintings of church interiors make this last category is especially interesting. The predominately Protestant churches are spare with somber interiors, devoid of decoration and flooded with a cool peaceful light. They are depicted inhabited by well-dressed men, women and even children and dogs. The scenes are almost never of prayer, but rather plain folk congregating, talking, visiting or strolling in what for them was a holy interior landscape. From these paintings it is clear that the citizens of Delft, while fully engaged in worldly pursuits were never far from their faith.

Considering the predominant religion, there are very few paintings of Christian subjects. There are shown two expressive biblical paintings; one of Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife and another of the Trials of Job, both by Leonaert Bramer. We also see the Delftware dish inspired by the depiction of Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife. Generally we are in a city where religiosity is finding an interior expression rather than bombastic expressions of belief that characterize the Italian Baroque to the south.

This new sensibility is found in the middle section of the exhibition, “Private and Public Spaces in Delft in the 1650s.” It is precisely this focus, so familiar to our Jewish worldview, that draws us into the singular universe of Vermeer’s paintings. Perhaps the first place to appreciate this approach is with Vermeer’s deceptively simple The Little Street (1658). It is considered one of the defining images of Delft and manages to summon, by virtue of the simplest of compositions, the glorification of the simple Dutch home. We “enter” the painting in the lower left and are immediately confined to the street that forms a solid band across the bottom of the picture. Rising above the street is an equally formidable blockade of house façade and walled alleyways. The only entrance is either through the open doorway into the alley or the main door of the house. In each of these entrances (understand the metaphorical power of these gateways) we find a woman. One, deep in the alley leading to an interior courtyard, is occupied with cleaning. And the woman in the main doorway sits calmly sewing. Once we have “entered” this house, via these good Delft women, we can imagine the rooms inside, flooded with light from the multiple windows and open shutters. We now can ascend up the stately façade that dominates the upper right half of the painting to reach the top of the painting only challenged by the heavenly sky on the left.

This painting owes considerable debt to another famous painting in the show by Pieter de Hooch (1629-1684), The Courtyard of a House in Delft (1658). This painting is even more explicit in its evocation of the perennial Dutch themes of household, duty and feminine virtue. The mother and daughter are busy with chores in the courtyard while another woman of the household is subtly framed at the entranceway to the street beyond. Comforting domestic activity within co-exists with an awareness of the outside world.

Young Woman with a Water Pitcher draws us deeper into Vermeer’s unique vision of the world. Again, a simple composition belies an amazing confluence of worlds. She stands caught in mid-action of opening the window, and yet serenely pensive since her gaze is not out the open window, but rather inside the room. She grasps the water pitcher seated in the basin, a symbol of purity in a moment of her private life. And yet she is hardly cloistered at home. While the open window allows for an exchange with the outside world it is the unobtrusive map, dominating almost the entire upper right quadrant of the painting that shifts the mental venue of the painting from a domestic to a worldly universe. The map is almost certainly of Holland and its shoreline; the world of commerce, politics and power. Vermeer’s vision of these worlds is not of conflict and contrast. Rather he conceives of his universe as unified and whole.

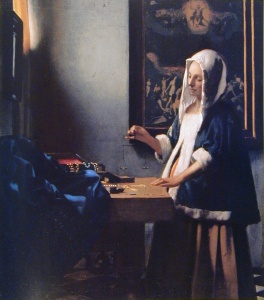

Woman with a Balance (1664) is perhaps even more obvious in Vermeer’s obsession with creating scenes in which the activities of the daily outside world coincide with a private feminine life. This painting takes this notion even further. She is holding a balance, but not weighing anything. She is, in her pensive and calm manner, making sure the balance is true. Jewels and gold are before her and she contemplates temperance and balanced judgment. The painting on the wall behind her depicts a last judgment.

It is important to understand just how singular Vermeer was as an artist. Eight of the fifteen paintings shown here are of women occupied in interiors of houses. Vermeer emerges in this exhibition as the painter of the interior landscapes of women. I know of no other painter so focused on the sensitivity and introspection that we associate with the feminine joined, in painting after painting, with the active life outside the home. Interestingly, this artist, who died at the age of 43, found consistent patrons for his work. He produced only two to three paintings a year, all of which were sold for considerable sums that was demanded to support his large family (including eight daughters). Therefore his work, while singular, was not idiosyncratic since he was able to find a patron who, one might assume, shared his point of view.

And the Jewish idea? Our belief that the entire world is ruled by one God, inhabited by a mankind commanded with mitzvahs whether in the private or public realm and founded upon the virtues of a stable home, temperance and balanced judgment was clearly shared, at least in spirit, by the Johannes Vermeer. If he was ever invited to a Jewish home in Delft Jewish community and happened upon the beginning of the Shabbos meal, surely a smile of recognition and approval would cross this great artist’s face upon hearing in Aishes Chayil (Proverbs 31:10-31); “An accomplished woman, who can find? Far beyond pearls is her value.”

Vermeer and the Delft School

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fifth Avenue and 82nd Street, New York