Paintings by Lloyd Bloom

Perspective is crucial to understanding. When Jews greet one another with “vos macht a yid?” it means something entirely different than the jeers of “yid” in the streets of Berlin. The one point perspective in early Renaissance painting defined an individualistic centered universe of humanism. In soaring ceilings of the Italian Baroque illusionist visions of vast heavens make the viewer feel insignificant and powerless, overwhelmed by the Counter Reformation Church’s total authority. Modernism’s chaotic points of view charted a culture in collapse, a fracture we are still struggling to mend. It all depends on where you stand. Perspective not only controls meaning but helps determine who we are as viewers.

Lloyd Bloom puts us in control. Many of Bloom’s paintings and carbon pencil drawings (recently on exhibition at the Chassidic Art Institute) impose an alien perspective on us. It is for us to decode it and eke out its meaning. The unexpected shift in point of view forces us to reinterpret the images from our normative understanding. The results are rewarding.

Sukkos first captures our attention by its aerial perspective. It looks down on a succah, peeking into a crowded interior filled with family and friends. Two hasids are toasting a happy family, lots of kids, smiling mom, sisters and a contented dad, as neighborhood children flock to the holiday celebration. Our vision rises and we see the surrounding houses clustered against a bucolic hillside until we reach the star studded sky, seven stars of yom tov illuminating the night. The fact that the viewer is above the scene allows us to savor its joy and, most importantly, appreciate its breath. The holiday is not just a personal or familial affair, it pictorially encompasses a universe.

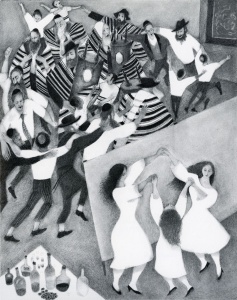

In a way Simhat Torah initially accomplishes the same perspective. Men dance ecstatically around three sifre Torah, the stripes of their tallisim interlocking in a rhythmic pattern. Arms akimbo or stretched out to one another all different kinds of Jews dance together. In the foreground three women dance behind a mehitzah. They span from youth to adulthood, their linked hands echoing the order and delightful chaos of the men above. A set table of wine and fruits forms the third axis of the triangle. The ability of the viewer to see each portion equally allows us to see their relationship, to understand how intertwined they really are. The women are in the foreground, central to the joy of the holiday. Their association with the wine, also found in the bottom of the painting, where one ‘enters’ the visual field, seems to find a foundation of home and children with the holiday of Succot and its climax of Simhat Torah.

Primarily a well-respected book illustrator, Bloom has an extensive background as a fine artist, studying at the Art Student’s League and the New York Studio School. Additionally he earned a MFA from Indiana University and a Fulbright Scholarship for his drawing and painting. He has lived in Crown Heights for many years. Many of the drawings in this exhibition were featured in Poems for Jewish Holidays published in 1986 and winner of the 1987 National Jewish Book Award for best illustrated children’s book. Nonetheless it is clear that there is nothing childish about his works. His use of perspective to establish a new context is always engaging.

At times Bloom adjusts our perspective in more conventional ways. Lot presents a father and his two daughters fleeing from the violent destruction their city. Fireballs plummet meteor-like from the sky, surrounding them with danger. Even while the trio is dashing in unison each glances in a different direction, engrossed in personal concern. They are interlocked with a future that we know will ensnare them in a terrible sin. Surprisingly we empathize with our distant relatives.

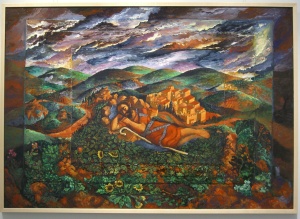

Jacob at Luz is part of a series of works he did in the 1990s probing the troubled sleep of the patriarch. This large painting started as a smaller work of acrylic on primed paper. Jacob is innocently asleep, curled up on a hill overlooking a small city with houses beaming with glowing windows. The subtle aerial perspective allows us to see the placid hills stretching to the clouds in a turbulent sky. Initially a simple and concise image, and yet the artist was not happy, somehow it needed more. Therefore he added three to four inches around each side, extending the landscape to greater vistas. Still not satisfied Bloom added two additional borders until the painting had grown sequentially almost one hundred percent larger. Now Jacob had a scale that simultaneously gave him stature even as the landscape became the visual expression of a world. Jacob’s dream had grown from an individual experience to one with vaster consequences. In another version of the subject, a smaller watercolor, Jacob is considerably more troubled in sleep, his hand covering half his face in anxiety. The rocks cluster around him, protecting him from the slash of light in the distance behind him that penetrates the night sky. Divine communication becomes divine interruption.

Bloom’s innovations can arise from his sensitivities as an illustrator, utilizing decorative elements to tease out new meanings. Finding Moses isolates Pharaoh’s daughter in a secluded lush environment of fantastic bull rushes that creates an overall decorative pattern. She is alone with the floating basket and the infant Moses, except for an almost totally hidden Miriam. The intimacy of the moment in its quiet beauty creates a tenderness that is not normally associated with the story. The concern of the princess for the baby is wonderfully touching, created by the grace of the figure bending over and the lush decoration encompassing her.

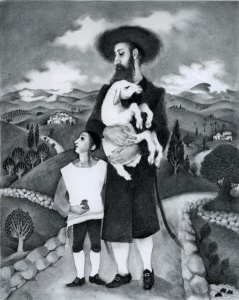

The Egyptian experience summons Passover and nothing encapsulates this holiday more than “Had Gadya.” It is this innocent ditty, yearned for at the seder’s conclusion, that summarizes the tragedy of the Jewish Diaspora. Its cruel logic of oppressions, cast within a folk fable, brings us into the present exile in which the angel of death always has the last word. Bloom’s vision of this subject offers us an optimistic beginning, a dream of balance. A benevolent father tenderly holds a white goat as he walks along a peaceful path with his young son who gazes off into a hopeful future. All is in balance in the surrounding countryside, everything fits this best of all possible worlds. And yet we, from our knowledge of where Had Gadya will lead, know that this too shall be shattered. It’s just a matter of perspective.

Richard McBee is a painter and writer on Jewish Art. Please feel free to contact him with comments at www.richardmcbee.com.

Lloyd Bloom, Paintings

Chassidic Art Institute

375 Kingston Avenue, Brooklyn, New York