Return to Sinai

I was transfixed the first time I saw Moses und Aron, the 1933 opera by Arnold Schoenberg. That was in 1990 at the New York City Opera and the performance at the Metropolitan Opera this December was no less exciting. The difficult, yet stimulating appeal of radical twentieth century music in the service of the biblical narrative only grew as I learned that this rarely heard masterpiece was a direct reaction to German anti-Semitism and might well be one of the first examples of Holocaust art. Schoenberg, a fully secularized apostate Jew, had responded at the height of his career to the rise of Nazism with what was essentially a call to return to Sinai.

Schoenberg’s three-act unfinished opera, written in German, grapples with one the central paradoxes that the Jewish artist must inevitably confront, namely the ineffable presence of God. Behind every narrative and at the foundation of all Jewish belief lies the presence that cannot be depicted, cannot be known and thereby, cannot be communicated. For the artist/composer, how does one represent, as Moses declares at the beginning of the opera, “Only one, infinite… omnipresent one, unperceived and unrepresentable God!”? Thus begins Schoenberg’s journey of questioning and struggle played out on the stage between Moses, Aaron and the Jewish people.

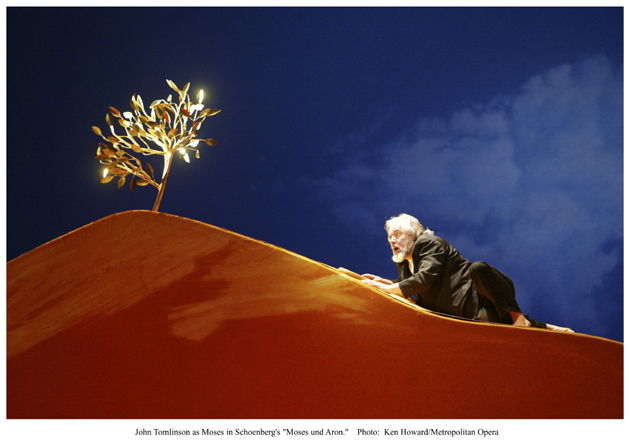

Quickly the characters are delineated. We first see Moses at the glittering burning bush against a stark blue sky. A Voice, represented by a six-person chorus, demands, “Be God’s prophet!” Moses argues, his voice rendered in spoken half song. The small chorus, alternatively singing and half speaking, vocally lurches forward, is now supplemented by a larger chorus and answers him; “You have seen the horrors… you must set your people free.” Egypt, at least for a moment, becomes Germany. Still Moses protests “But my tongue is not flexible.”

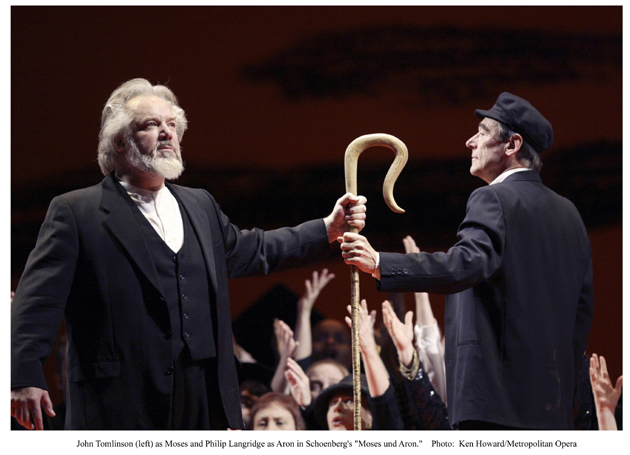

Melodious flutes announce Aaron and soon he will become his brother’s mouthpiece. He will transform Moses’ revelation into a form the people can understand. They are still mired in paganism but yearn for a leader. They don’t know what to expect, suspicious of Moses and yet wanting to believe in a God “that will save… will make us free… stronger than Pharaoh!” Aaron will sing beautifully as Moses speaks stiffly, explicating the invisible God. And slowly it will dawn on Moses that Aaron’s interpretation, catchy little tunes and clever turns of a musical phrase might sully the purity of the ineffable. Aaron is the artist, the activist politician who must please the populace, as Moses remains distant, uttering strange abstractions. For Moses, the reluctant prophet, his brother’s skill is his only connection to the people he wishes to free.

Schoenberg’s artistic quest began with his own apostasy to Protestantism in 1898 at the age of twenty-four. Totally bereft of any Jewish education his conversion was driven by the desire to succeed in the deeply prejudiced Vienna music world that reflected his deep love of German music. His revolutionary compositional method, developed around 1921, eventually became the twelve-tone scale and the basis of much late twentieth century music, confounded audiences and critics alike. In spite of his controversial output he had by 1925 secured the prestigious professorship of composition at the Prussian Academy of Music in Berlin. Nevertheless, beneath this facade of success all was not well.

In the summer of 1921 Schoenberg went to the resort of Mattsee near Salzberg for a much needed vacation with his family. They were summarily turned away by the township policy that “Jews are unwelcome.” Even if Schoenberg had produced the requisite baptismal certificate, the boldness of the anti-Semitism repulsed him. Two years later in 1923 he heard and believed rumors that his friend, the non-objective painter Wassily Kandinsky, supported an anti-Semitic atmosphere at the newly formed school of modern design, the Bauhaus. These two incidents shattered Schoenberg’s illusions concerning his role in the European music world. More importantly the rising tide of anti-Semitism crystallized his developing interest in Judaic themes in his music.

He had been moving in this direction for some years in any event. As early as 1912 in the initial flurry of Modernist musical creativity, he stated his interest in composing an oratorio about, “modern man, having passed through materialism, socialism, and anarchy and despite having been an atheist, still having in him some residue of ancient faith, wrestles with God and finally succeeds in finding God and becoming religious.”

Moses und Aron finally concretizes this need for an encounter with God. In a very real sense the portrayal of the Jewish people in the opera is the essence of that struggle. At first they mock the idea of an invisible God, laughing out loud. Then they are shocked into a kind of primitive belief by the miracles of the staff and of the leprous hand, as directed, shaped and interpreted by Aaron. Of the staff, now a writhing serpent, then a staff again, Aaron declares; “In Moses’ hand a rigid rod: this, the law. In my own hand the most supple of serpents: discretion. Now stand so as it commands!” Finally at the end of the first act, the people triumphantly accept their role as a chosen people; the stage rises on five levels to reflect the law they are about to receive. The people yearn to be free from toil and misery and free to worship the one God. Schoenberg’s music rises in atonal triumph to greet the curtain.

The dichotomy between the man of God and the artist appears again and again as a reflection of Schoenberg’s own struggle to return to Judaism. Within a year after he had finished the first two acts of Moses und Aron he was forced to flee the Nazis in 1933. On his journey into exile in America he first went to Paris and formally returned to Judaism in a ceremony where the artist Marc Chagall was a witness. Within an artistic setting Schoenberg had returned to his people, clearly for him the only viable answer to the anti-Semitism festering in Germany and Austria.

For some years before Schoenberg had been working on this notion, i.e. an answer to the “Jewish Question.” He struggled with an oratorio, Jacob’s Ladder, between 1917 and 1922. In 1926 he started what scholar Moshe Lazar characterizes as “a propaganda play and a passion play” that would serve as an alarm and a call to arms “to dream and articulate his plans for a national and spiritual rebirth of the Jewish nation.” The Biblical Way unfolds in three acts, at first representing various Jewish groups of Central Europe; orthodox, capitalist, socialist and Zionist. A leader emerges, Max Arnus, who represents to Schoenberg a combination of three historical figures; Herzl, Moses and Aaron. In the second act the Jewish people are seen in “New Palestine,” a temporary Jewish homeland outside of Eretz Israel, forging the first stages of communal accommodation. The last act reveals a social breakdown; the populace rebels and murders their leader Max Arnus (this notion probably originated in the work of a German scholar, Ernst Sellin who speculated in 1922 that in light of his analysis of the Book of Hosea, Moses was murdered by his own people during an unnamed rebellion. Freud capitalizes on this notion in his bitter 1938 criticism of Judaism, Moses and Monotheism). The Biblical Way ends as a tragedy redeemed by the notion that “the Idea has been thought, the thinker is dead, but the Idea lives on.” The dual concepts of a Jewish homeland and of the need for a strong leader were joined to the inevitable encounter with God in his next work, Moses und Aron.

The second act finds the seventy elders waiting impatiently for Moses’ return in an enormous bleak shell beneath a burnt palm tree. The Mountain of Revelation seems forlorn in the distance. Aaron attempts to mollify the people, finally dragging in a grotesque rag calf that is adorned with the people’s gold and jewelry. In a startling stage image, the people begin to shuckle and daven towards the idol. While Schoenberg’s music here is evocative, filled with stark contrasts and driving rhythms the staging of the remaining worship of the golden calf and subsequent orgy of drunkenness, dancing and human sacrifice is no more than a shallow glitzy evocation of lewdness and debauchery. Paganism never looked so fake and boring. Luckily Moses soon descends (literally on a staircase lowered from above) to condemn and destroy the golden calf. Moses demands, “What have you done?” Aaron answers, “I heeded a voice from within.” Moses commands, “See now the power which Idea has over both word and image!” “But the people… can grasp only part of the Idea…” Aaron explains before he accuses the Tablets of the Law as being mere “images also…” Furious, Moses smashes them, desperate to regain the purity of his original revelation. The Jewish people are now led across the stage by God’s signs, the Pillar of Fire and the Pillar of Cloud and as the mountain closes upon them Aaron joins them on their march to the land of milk and honey. Moses is alone again as he bemoans the inescapable paradox, “Unrepresentable God! Inexpressible, many-sided Idea… thus I am defeated… O word, word that I lack!” The curtain descends on Schoenberg’s masterpiece.

Arnold Schoenberg utilizes Moses und Aron as a powerful paradigm to challenge the Jewish people to return to their Land and to their God in spite of the inherent difficulties. At his death in 1951 he had still not completed the third act; the libretto alone stands inconclusively as he worked tirelessly, engaged in letter writing and agitation for the rescue of European Jewry and the establishment of a Jewish homeland. His music, the complex structure of the 12 tone scale in which a series of twelve chromatic tones are chosen to determine the entire pitch, melody and harmony of a given piece, not repeated until played out, actually echoes the complex and seemingly arbitrary structure of the halachic system. Schoenberg, faced with the terrors of the 20th century, embraced the Torah and the ineffable God, whose very hiddenness, hester panim, would characterize our understanding of the Holocaust. Schoenberg, a musical prophet, had returned to Sinai.

I gratefully acknowledge the research of Moshe Lazar for background material, especially in the Journal of the Arnold Schoenberg Institute, vol. 17, 1994.