The Choice of Photography

What makes a great photograph? Is it something that merely warms the heart or unlocks the memory? Or might it be something more? Great photographs rise above our individual loves and ethnic interests and exhibit at least four essential elements; compelling composition, clarity of image, engaging subject and technical excellence. Without these components you end up with a “nice” picture that remains a snapshot relegated to a shoebox of memories. The image, Succoth, Man with a Prayer Shawl, Bedford Avenue (1965) by Irving I. Herzberg is intriguing. Much more is here than mere familiarity, in fact this grand photograph answers each categorical imperative of good photography in the affirmative.

The half-opened door on the left edge of the photograph acts as the entranceway to the subject; the hasid in a tallis. From that introductory space our eye is directed to the right to the exact center of the image, the subject’s face. His head surmounts the enormous shape created by his tallis, which seems to support him quite beyond his physical body that is lost in the shadows. The vertical stripes of the tallis echo the vertical divisions of the image and even mimic the foreground railing. The diagonal stripes create a tension to this motif and are themselves reflected in the line of man’s eyes. This left to right pattern is played out across the surface and is broken by the strong sunlit gaze of the man’s eyes shooting off to the left. These elements are the compositional mechanics that provide compelling visual interest in the photograph.

At first glance we recognize our subject as an older man peering out of a doorway probably captured on Chol HaMoed Succos since he is not wearing tefillin. The strength of his gaze is what engages us and draws us into a hidden narrative. Exactly what is he looking at and why? This intrigue makes us want to continue to search the composition for an answer. All of these elements are presented in a sharp, clear print that makes for a compelling portrait of one man captured in a slice of time.

The genius of photography is its ability to freeze time and preserve it for the future. Because it exists in such a specific time the photograph can strongly suggest the “unfrozen” time around it. The photographer is artistically responsible for choosing when and where he captures that slice of time. Irving Herzberg is such an interesting photographer precisely because of the creative choices that he made at each step in the photographic progress.

Although considered an amateur he worked with photography all his life. From the time of his bar mitzvah, when he was given his first camera, until 1992 when he passed away at the age of seventy-seven, he spent his life documenting his beloved Brooklyn. After his death his life’s work of over twenty-three hundred photographs was donated to the Brooklyn Collection of the Brooklyn Public Library. He began documenting his beloved city, Brooklyn, in the early 1950’s

His work can be divided into a series of five subject areas; Jewish life on Ocean Parkway, a candid subway rider series (working with a hidden camera), images of people in Coney Island and Hasidim of Williamsburg. A selection of twenty-nine photographs from the Hasidim series is currently on view at the Brooklyn Public Library, Central Branch, until September 29, 2002.

The Day Before Passover (1970) tells its story by diverting our attention. The two main elements in the composition; the folded bedding being aired out on the window sill and the two children at the corner of the window offer at first an incongruous juxtaposition. The rectangle formed by the bedding is mirrored (pardon the pun) in the window frames above. Yet, how do the smiling children compositionally relate to these geometric elements? It is this tension that forces us to ponder the nature of the preparation occurring here.

The bedding needs to be clean and fresh for the upcoming holiday. Its preparation, dominating the photograph, prepares us to realize that a major purpose of the holiday of Passover is the preparation of children in their role as the next generation of Jews… “You shall tell your son on that day, saying: ‘It is because of this that Hashem did so for me when I went out of Egypt'” (Exodus 13:8).

This pictorial drasha is made possible by Herzberg’s very specific choices. The picture could have been cropped to simply focus on the charming children or it could have been expanded to include a more general view of the window and building façade. It was the photographer’s specific compositional choice that allowed this meaning to emerge.

Barber, Lee Avenue (1967) provides us with a very different kind of visual treasury. The composition is not nearly as striking as the previous two photographs, but in its subtle way it manages to tell us a great deal about the Williamsburg world and the interaction between the old country and life in America. The lettering on the awning and in the shop window is what first attracted my attention. “David’s Barber Shop” becomes transliterated from English to Yiddish; “Shomer Shabbos Barber Shop” in Hebrew characters. The same phonetic spelling is used in the sign advertising “Special Haircut.” While not uncommon, this points to the comfortable use of English words as part of Yiddish speech, even though there are perfectly fine Yiddish words available. This linguistic assimilation reflects the persistent influence of modern American culture on the Hungarian Jewish population of Williamsburg while the piety of the people remains unchallenged.

The store is proudly Shomer Shabbos and proclaims that there is a separate room for ladies with female stylists. This modern/traditional relationship is reflected in the nature of the people captured by Herzberg on the right side of the photograph. The older and more traditional couple is chatting with a much more modern and fashionable mother with her daughter. What looks like a snapshot reveals itself upon closer inspection to be a sociological study of generational and influences in Williamsburg society.

Irving Herzberg was an important photographer and it is satisfying to know that in his lifetime he did not go entirely unnoticed. Working out of a modest darkroom in his home, he exhibited his work in the Jewish Museum in 1965 and published a book with George Kranzler in 1972 entitled, The Face of Faith: An American Chasidic Community. As a true artist, he simply kept on taking pictures and making prints, with or without notice or acclaim.

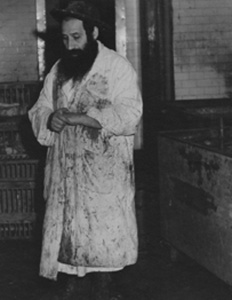

The surety and sensitivity of his vision is perhaps best exemplified in The Shoichet (1969). This photograph is simplicity itself. By placing the subject off center the image is ever so slightly upsetting. This compositional device, in conjunction with the stark contrasts of his blood splattered smock and the dimly lit shop around him, delivers the emotional impact of its subject. Herzberg balances the grim environment of death with the intense contemplative stance of the shoichet. Because of the graphic simplicity of the image we are drawn into the mind of the butcher; we feel his fatigue after slaughtering chickens for hours on end and can imagine his thoughts that the taking of life of any of God’s creatures, even a lowly chicken, has meaning and cannot be treated lightly.

Seriously considering each of life’s little details, making sensitive and intelligent choices as to when and where to capture a slice of that life on film, and finally crafting elegant prints that display these creative choices; these are the elements that makes the insightful and creative images by Irving Herzberg truly great photographs.

The Hasidim of Williamsburg; Photographs of Irving I. Herzberg

Brooklyn Public Library

Central Library Grand Army Plaza, Brooklyn, New York