Shoshana Golin’s Windows

Shoshana Golin’s cycle of etched glass windows at the Young Israel of Hillcrest fill the fifty year old sanctuary with light and textual meaning that transforms the synagogue space, illuminating a new environment for the congregation.

The window cycle begins with the three windows in the women’s section, Creation, Shabbat and Rosh Chodesh, and continues on the lower level of the men’s sanctuary with four tall windows that elucidate the Yom Tovim and Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. Thus the entire Jewish cycle of creation and celebration is represented in natural light filtered and shaped in the medium of glass.

Golin’s work is familiar to us from the etchings she did in the Book of Esther Series (reviewed here November, 2001). Those five etchings explored what I characterized as “the masks of Esther,” the hidden nature of Esther as a frightened adolescent, her need to hide her personality, desires and identity. Reflecting the hidden nature of God in the Megillah, Golin’s images explored what cannot be seen, what cannot be known and what cannot be revealed, an echo of the inherent mystery that life presents us with. The Hillcrest windows, fabricated by John Nutter Studios of Vancouver, Canada and finished in 2005, are in a way the exact opposite of the Esther series.

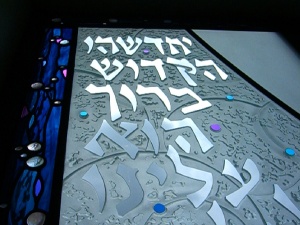

Text dominates the graphic design that unifies each window. The Six Days of Creation are glimpsed in six concentric circles infused with letters, words and phrases. Numerous types of glass, some letters totally transparent, some etched on the surface, other sandblasted, create multiple images as the viewer’s perception constantly changes while moving along the window and thereby shifting the outside light source. Light from the sky, now clouds and trees, and then buildings just across the street animate the windows. The outside light and the position of the viewer determine the visual experience. In the next window, the Shabbat, a sweeping arch unifies Creation with the last window in the women’s section, Rosh Chodesh. The blessing for the new month dominates the Rosh Chodesh window just as Shabbat prayers dominate that window. Each window is contained with a luminous and complex blue border that frames a perfectly intelligible text. Esther was about mystery whereas the windows are about revelation.

When one thinks of decorated synagogue windows the Chagall Windows at Hadassah Hospital at Ein Kerem in Jerusalem immediately come to mind. In the windows of the twelve tribes the bold structural tracery is allowed to interrupt the pictorial composition while the thinner tracery animates the surface, creating a kind of expressionistic brushwork in glass. Text is minimal, only delineating the tribe and a biblical quotation or blessing describing the progenitor. Chagall’s figurative elements are never fully human, only animals, fish, birds, landscape, hands in blessing and symbols dominate the deeply expressive colors. The rich profusion of color and choice of images is an instructive comparison.

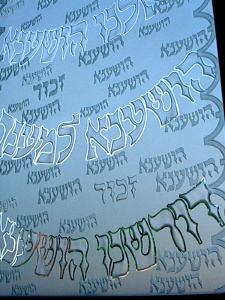

Golin’s windows are almost totally without color. Subtle differences are seen within the whites, creams and blue tints, but her predominant modality is tonal, shifting between thickness in glass and occasional dots of pure dichroic glass that changes color in different lights. Her designs and texts are submerged in the glass itself, forcing the viewer to look closely to fathom exactly what is going on. The men’s section is intentionally more complex, creating a textual tapestry. Pesach features the song at the sea, Az Yasir, while Shavuot expresses the elemental nature of words themselves in the Akdamot; “In introduction to the Words, and commencement of my speech, I begin…” Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur proclaims repentance, prayer and charity above the thirteen attributes of God, intoning the verbal foundation of judgment and forgiveness. Finally Sukkot/Shemini Atzeret floods the glass with seventy hoshanahs and six incantations of z’chor. The text itself has become the subject, drenched in the shifting light that surrounds the synagogue. These windows proclaim the primacy of text, luxuriating in the physicality of its writing while suppressing the sensuality of color and image, opting for a clarity that figuration seldom allows.

Shoshanah Golin’s commission of the Hillcrest windows was to transform a sacred prayer space. Historically rabbinical objections to synagogue ornament was that it could distract the worshiper, weaken concentration and frustrate the desire to communicate with the Divine. Golin’s windows assure that any distraction will be simply another text, another religious connection that will inevitably return one to prayer, to text, to meaning. In Golin’s windows there is no way out, the only option is to pray bathed in a light informed by text.