A Painting by John Dubrow

From 1997 to 1998 John Dubrow got to know the World Trade Center fairly well. He made many paintings from a high vantage point on the 91st floor in a temporary studio granted him by the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council. His heavily worked cityscapes built solid compositions out of urban structure, color and space and define an important body of his work at that time. After September 11, 2001 he was, like most New Yorkers, devastated by the attacks and the destruction of the World Trade Center. He wondered how he could return to cityscapes after his city had been so violated and his artistic milieu shattered. In the wake of the smoke, ash and collapse he groped for an artist’s response to this mass murder.

A few weeks later a close friend mentioned that he was studying the attack of the Amalekites against the Israelites in Exodus in conjunction with the events of 9/11 and the impending war in Afghanistan. Dubrow was intrigued by the subject and its implications but immediately thought, “I don’t do that kind of painting. I don’t make biblical art.” And yet he started drawing on a blank canvas as the initial image came to him. First the three figures were very large, and then he changed the scale drastically. He worked two years on the painting, Rephidim, that was shown at the Salander-O’Reilly Galleries. In his recent exhibition it is easily the most complex, ambitious and successful painting of this current work.

The story of Moses raising his hands to insure an Israelite victory over the Amalekites (Exodus 17:8-16) is found sporadically throughout art history. The frontal image of Moses with his arms stretched out in prayer flanked by Aaron and Hur is first found in a fifth century nave mosaic in Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. After that is it seen in scattered illuminated Christian manuscripts that understand the subject as “an important antetype of salvation through the cross [because of the cross-like posture]” and demonstrate “the efficacy of prayer in war…” Other medieval works such as the Moralizing Bible (1245) use the image as a liturgical symbol, paralleling Moses to a priest offering the Mass at an altar. In a church in Reims, France a floor tile represents Moses with one arm raised high with the help of Aaron and Hur in an attempt to control the outcome of the battle. In the later Middle Ages the image shifts from the frontal view (more typical of symbolic and sacred interpretations) to a profile view that gradually expresses a more naturalistic and secular understanding.

Not surprisingly there is a Hebrew manuscript, the London Miscellany, created in France in 1278 that depicts Moses’ hands together in prayer (perhaps in opposition to the earlier Christian pose), supported by Aaron and Hur. He seems puzzled as they attempt to help him.

From the late fifteenth to the seventeenth century the subject of Moses fades into the background of depictions of the battle with the Amalekites. The Lubeck Bible (1494) shows the trio far off to the side behind the main battle, while Poussin’s early painting of the Battle of Joshua against the Amalekites (1625) features the Moses group barely visible in the distant background.

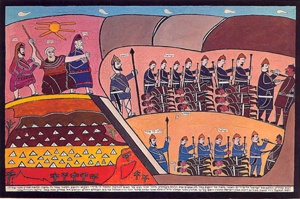

Suddenly in the twentieth century the theme reappears prominently on a Torah Ark of the Bezalel School in Jerusalem (1916-1925). On the bronze doors it is one of six episodes in the life of Moses testifying to faith and strength in battle. The theme is similarly patriotic in what is easily the most public display of the subject, Benno Elkan’s monumental bronze menorah given to the Israeli Knesset in 1956 by the British Parliament. On the upper register of the central branch the gestures are clear and unequivocal. Aaron and Hur are forcefully helping Moses keep his arms up during the battle, which must have seemed extremely relevant during the first years of struggle after Israeli independence. Finally the naïve artist, Shalom of Safed shows Moses at the War with Amalek (1964) furiously leading the battle, staff in hand, with little need for the help of Aaron and Hur. The subject clearly lends itself to multiple interpretations throughout the ages.

John Dubrow was unaware of any of this previous history as he faced numerous problems attempting to narrate this text. Quite alone he confronted the story at face value and struggled with its meaning for the contemporary world. His creative composition and forceful use of impasto, especially in the sky and landscape, have effectively surmounted the dangers of naturalism and archaic costuming which would have rendered the image an illustration. By creating an abstract surface, the planes of light and dark on the figures and their clothing hold the painterly surface even as the carefully modulated blue sky summons the vastness of the Sinai wilderness. The figures are off center and somewhat overwhelmed, making us aware that the vast sky and landscape operates as a narrative character, perhaps as the Divine Presence, which Moses must summon to Israel’s aid. And yet there still seems to be a struggle among the trio.

The artist conceives of each figure differently. Since each face is partially obscured by shadow the bodily poses and relationships must narrate the text. Aaron submissively kneels slightly behind Moses, his arms interlocked, even confused, with Moses’s. Hur, in the center of the painting, is the largest figure, bare-chested, and the most forceful in lending support. The passivity of the seated Moses creates the most tension and concern. But of course that simply returns us to the puzzling text. Why does Moses not lead the Israelites himself; why does he need to sit; why does he need help in supplicating God? Remember Moses will soon spend forty days and nights while fasting learning Torah with God Himself. Moses is no wimp. Dubrow’s painting confronts us with these questions even as the artist casts the subject into our contemporary crisis.

Palms open to the vastness of the blue sky (a clear blue sky just like on 9/11) expresses Moses’ passive attitude. God’s will be done. His aides struggle with him; it may not be so simple they say. Amalek, the unequivocal enemy of Israel, has viciously attacked without cause. We must do battle with them, but we doubt the absolute justness of our cause. We are uncertain, divided and deeply wounded. Our fate is uncertain because we carry the sin of doubt from the Waters of Contention at Rephidim. We doubted God and Moses doubted the Children of Israel. This doubt and confusion permeates the painting just as we in the West have re-examined our relationship with Islam and the multitudes of the Third World. There is no doubt about the evil of Amalek and the terrorists. What is unclear is what we can expect as God’s response and how do we request His salvation. Pray, or fight or both? Have we squandered the bounty that God has given to us? Are we worthy to triumph over this enemy who would annihilate us? The impressive scale and size of the painting (unlike almost all previous miniature versions) places the furious battle in the unseen foreground of the canvas. The battle is in the space between the painting and us. The outcome even after the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq is still uncertain.

John Dubrow’s Rephidim is the artist’s response to the mass murder of 9/11. The biblical context confronts us with difficult questions that defy easy answers. Our vulnerability under that awesome blue sky may be the most salient feature we can salvage from the conundrum of our times.

John Dubrow: Paintings, Rephidim

Salander-O’Reilly Galleries 20 East 79th Street New York, N.Y. 10021

(Meyer Schapiro’s Words and Pictures, 1973 is the source of the pre-20th century background information on this subject)