Three Works of Jewish Art

“And thy life shall hang in doubt before thee…” (Devorim 28:66). Rav interpreted this as applying to Israel in the time of Haman (Esther Rabbah, Proem). This time may be upon us. There can be no certainty when war is imminent and constant terror threatens our homeland. Three very different artists understand various shades of this perspective as they explicate the role of Mordechai in the Book of Esther.

Rembrandt van Rijn, the seventeenth century master, created The Triumph of Mordechai in 1641. Teeming with figures, this etching portrays the bizarre turn of events as Haman is forced to honor his archenemy, Mordechai (Esther 6:10-11). Haman leads him through the streets of Shushan on a royal horse garbed in royal robes, proclaiming, “This is what is done for the man whom the King especially wants to honor!” Rembrandt has filled the image with figures bowing down in homage or recoiling in laughter and shock at the spectacle of the kingdom’s prime minister reduced to a mere lackey and herald.

Ensconced in a balcony in the upper right, the royal couple observes the scene in regal detachment in contrast to the agitated crowd. More surprisingly though, the main characters, Mordechai and Haman are strangely passive in the etching’s off-center focus, an uneasy calm in the midst of social upheaval. These two heads, Mordechai’s silhouetted against the sky and Haman’s depicted in high contrast, form part of a triangle completed by the horse’s head. Finely detailed, its head twists unnaturally toward Haman and gazes past him to the viewer. The horse acts as the symbol of living royal power in the narrative and mediates the tension between Mordechai and Haman. It is through that power that the resolution will finally be sealed.

This image evokes an ancient fable from a distant land. Haman is exotically turbaned and Mordechai’s hat and robes are fantastic even for seventeenth century fashion. All the more fantastic is their calm at the center of a threatening storm. That is the most unsettling aspect of this image. Mordechai the Jew understands that his people are slated for extermination and his personal triumph will not alleviate the cruel decree. Haman has been personally disgraced before his enemy. Both are in the midst of a terrible crisis, yet they show only stoic consternation. The tension is exquisite. Each seems trapped in a psychological morass that will ultimately affect the fate of their people.

Rembrandt’s late Renaissance vision is bound up in the personal and social relationships of the biblical fable. He can hardly imagine the annihilation of the Jewish people that Haman has called for.

John Bradford’s giant painting (9′ x 12′) of the Triumph of Mordechai is radically different. This work is clearly informed by the murderous history Jews experienced in the twentieth century. The horse, now wearing a golden crown, stares at the haughty Haman who struts alongside the mounted Mordechai. The nexus has shifted to Haman and the horse at the exact center of the painting. A lurid yellow silhouettes Mordechai who has turned away from the action. Mordechai the Jew, passive and yet superior in position, is gazing deep into the painting, into the future as it were, where the political struggle between Haman and the King (here represented by the crowned horse) will be finally resolved.

Haman, chin jutting up and arrogant, is an echo of a twentieth century fascist, a puffy-faced Mussolini still confident of his power. Bradford invites us to pass through the gate depicted at the left and enter into an understanding of the present dangers posed by those who threaten the Jews.

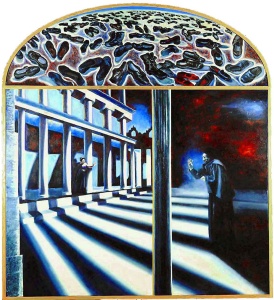

Esther and Mordechai (2002) by Janet Shafner is distinctly political in approach. Simple colors of white, black and blue with hints of red underpainting create an initially theatrical impression of authority radiating from the corridors of power. The drama is further emphasized by the figure of Esther centered by the columns and positioned in the center of her portion of the painting. She reaches out to Mordechai who is isolated in the right section. He is in sackcloth and ashes, horrified at the terrible decree against the Jews. He commands her to plead for the lives of her people (Esther 4:12-17).

The stark separation between Mordechai the Jew, cognizant of danger and yet powerless, and Esther, the hidden Jew, who has access to power in a non-Jewish world, could not be greater. Shafner demands that the viewer understand the necessity of political manipulation by which “insider Jews” influence events that are crucial to Jewish survival. Then she adds to the dialogue a vision of the consequences of failure.

In the lunette above the action is a mysterious landscape of abandoned shoes. They refer to the times when we could not control events and Haman’s descendants devastated us. In the mussaf for Yom Kippur (ArtScroll Machzor, pg. 587) a piyut moans, “We have erred, our Rock; forgive us, our Molder,” and tells of the martyrdom of the ten sages. The Roman emperor wished to incriminate the sages in the sale of Joseph by his brothers. He “ordered that his palace be filled with shoes.” Shoes? We are told that when Joseph was sold the brothers used the money to buy themselves shoes.

With the debt still outstanding, the great sages, the descendants of Joseph’s brothers, were still guilty, and therefore, libel to the death penalty for kidnapping. Subsequently they were all murdered by the Romans. Closer to our own time, images of abandoned shoes, clothing and possessions crowd our Holocaust memory of mass executions and deportations. The Shafner painting is telling us we cannot afford to fail at politics.

Each artist has something to tell us about how Mordechai, Esther and Haman relate to their social and political reality. The messages and indeed warnings embedded in the artwork are clear. It is up to us to bring them into the present and act on them for the sake of our people.