Missing Women of the Book

Jews and books… as natural a combo as love and spring, wine and cheese, and for sure God and His people… they are meant to be together. Proud to be known as the People of the Book we parade the Torah, Talmud and countless writings as our special inheritance. And beyond simple piety, the contemporary Jewish contribution to secular literature is legendary, marking us as a nation who both read and write voraciously.

But what about making books, specifically artist’s books? These hand-made objects utilizing text and some kind of book-inspired format are a particularly modern idiom and it seems Jews have made their mark here too. This relatively recent phenomenon is brilliantly explored in the traveling exhibition, Women of the Book: Jewish Artists, Jewish Themes, curated by Judith A. Hoffberg, recently at the JCC of Miami and at Rutgers University, Camden.

Women of the Book, exhibiting over one hundred works, concentrates on three principle themes explored by Jewish women artists: Women on women; women and Judaism and finally the Shoah. The subjects reveal the contemporary concern with feminism, ethnic identity and the Holocaust. And yet for all the richness of this exhibition there is something missing in a perverse kind of cultural myopia. The women of the Book themselves are curiously underrepresented. One wonders where Sarah, Hagar, Keturah, Rebecca, her nurse Deborah, Rachel, Leah, Bilhah and Zilpah are hiding.

Nonetheless the first two concepts, feminism and identity are dealt with forthrightly. We see them here frequently conflated so that being Jewish is filtered through a feminist perspective. Ita Aber’s Gamma combines an ancient Greek symbol that identified women’s garments with her daughter Mindy Aber Barad’s text on the daughters of Zelophehad. They demand women’s inheritance rights: “How come they get and we don’t,” finally demanding from Moses “Who will remember Zelophehad when we’re gone?” Out of their mother/daughter relationship blossoms a Jewish feminism based on the Torah text.

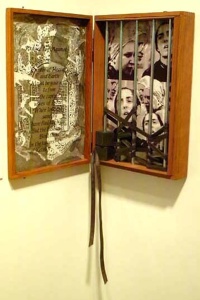

Similarly, Prayer for Agunot by Viviana Lombrozo unflinchingly addresses a particularly Jewish crime. One side of the open book fashions a tattered ketubbah with the “Agunah’s Prayer” that beseeches “Creator of Heaven and Earth… free the captive wives of Israel… when love and sanctity have fled the home…” Opposite this are images of contemporary women behind bars. Faux tefillin and straps bind the bars together. The painful struggle to find a resolution between halacha and its contemporary application reverberates throughout the piece.

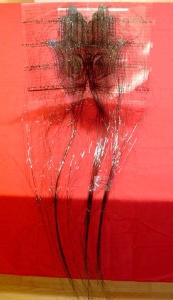

An ethereal presence is felt in Pentimento XV/Hamsa by Claire J. Satin as thin dark threads form a hamsa whose wrists trail off into strands of hair. The illegible lettering of this “mourning book” traces a circular text combining the image of what would be one’s own hands sheltering the face in sorrow. The delicacy of the object and its image touchingly approximates tears of grief.

The format of the artist’s book is characterized by an integration of text, image and decorative elements, sometimes to the point of eliminating the text completely. As an art form it is a modern manifestation of ancient antecedents, starting most notably with Egyptian papyrus scrolls that feature brilliantly rendered figures fully integrated with hieroglyphic text that itself contains figurative and symbolic elements. Islamic and Hebrew sacred manuscripts were illuminated transforming letters into pictorial elaborations that quickly included ornately designed pages incorporating fantastic designs and, in the Catalonian Haggadot, many figurative representations. While seldom signed by individual artists, these unique manuscripts were clearly artist’s books as were the Christian illuminated Bibles and prayer books produced in fourteenth and fifteenth century Europe. The invention of moveable type and printing almost completely eclipsed this art form until the rise of modernism urged artists to experiment with all media, including the humble book. The Russian Constructivists explored the possibilities of the art book while the Italian Futurists celebrated the use of creative typefaces, modern design and the antinomian use of language. The twentieth century saw the expansion of this medium to include limited editions of artist’s books, some of which adhered to a text like Chagall’s The Bible and others celebrating the visual as Matisse’s Dance, both published by the famous publisher Verve. The modernists reveled in the freedom and creativity of experimentation.

The Jewish artists here also freely shift between the visual and the textual. An aspect of the feminine in Jewish identity is seen in Inside by Rose-Lynn Fisher. Her x-ray images of pomegranates shock the viewer with a kind of biological imperative, summoning the sonograms that have become common with expectant mothers. The deeply Jewish metaphor of the pomegranate fruit’s fecundity is lovingly elucidated with ten images on rare handmade paper sewn on each page.

Judaism’s aggadic textuality is perhaps best expressed in 36 Steps of the Lamed-Vov by Joyce Cutler-Shaw. This idiosyncratic “book” is composed of thirty-six photographs of a garden installation in San Diego, California. Inscribed stone tablets follow a path in an art garden and tell the story of the venerable thirty-six tzadikim through whose merit the world is allowed to exist. The text on the stones slowly engages our interest, glimpsing their humble sensitivity to human suffering and the tremendous responsibility they bare unknown even to themselves. The gentle sadness of this artwork combines the reality of stones in a garden with the illusion of pages of photographic text, each playing a role in understanding the sadness of the Jewish Diaspora.

Many feminists see sadness in the silencing of feminine voices in Jewish history. But where in this exhibition are Dinah, Tamar, Potiphar’s Wife and her adopted daughter, Asenath (daughter of Shechem and Dinah), Joseph’s wife, Asher’s daughter, Serach, Pharoah’s daughter; not to mention Jochebed, Zipporah, Miriam, the Hebrew midwives Shifrah & Puah, the brazen sinner Cozbi, killed by Pinchas, and of course Esther, along with Vashti and Zeresh in the Women of the Book. I miss them.

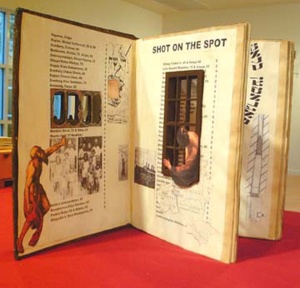

The sense of loss, sadness and pain summoned by the Holocaust make it one of the most common subjects for Jews and this exhibition is no exception. Many of the pieces with this theme seem to dispense with a specifically feminine voice, such as Shot on the Spot by Terry Braunstein. She takes an antique book, cuts a window into the interior of six leaves and lists the names and ages of an entire village that was rounded up and murdered by the Nazis. Evocative period photographs of the villagers and an actual rifle shell make this a brutal memorial. Additionally cutouts of overly dramatic Renaissance figures turn the memory of this pogrom into a scathing accusation against the histrionics of Western culture.

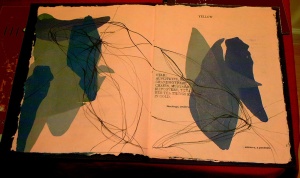

Many others maintain the feminist perspective. Voce (Aiming for Symmetry) by Deborah Davidson charts her own responses to her great-grandmother’s letters from Auschwitz. The work combines block letter text that appears and then fades under washes of color and ink drawing, suggesting a chaos and modernism that threatens to swallow her familial voice from so far away. It is surely one of the most poignant pieces in the exhibition.

And yet we return to the nagging question. With so much provocative, insightful and creative work in these Jewish women’s artist’s books, why the omission of the richness of the Women of the Bible? The breath and variety of women’s experiences, like those of Deborah, Hannah, Bathseba, Jael, Judith, Delilah, Avigail, Michel, Abishag, Jezebel, Elishevah, Shoshana, Peninnah, Ruth and Naomi is incomparable. How is it that most of them are absent?

In light of this excellent exhibition, a veritable chorus of Women of the Book call out to Jewish artists, male and female alike. How could we not answer?

Richard McBee is a painter and writer on Jewish Art. Please feel free to contact him with comments at www.richardmcbee.com.

Women of the Book: Jewish Artists, Jewish Themes, curated by Judith A. Hoffberg. @ www.colophon.com.