Lights at the Israel Museum

From “Let there be Light” of Biblical fame to yesterday’s sound and light show, the notion of light as a metaphor or aesthetic tool is worn and tedious at best. Even as pietists, who claim dominion over Divine emanations, battle with modernists who assert visual primacy, nonetheless as a serious metaphorical concept “light” is cliched and superficial. Therefore it is with considerable courage that curator Amitai Mendelsohn at the Israel Museum has fashioned a surprisingly handsome exhibition of forty artist’s works that address the problematic subject of light.

Twelve winners from the Adi Foundation form the aesthetic heart of the show. This competition challenges contemporary Israeli artists to connect Jewish ideas with contemporary art. The results are a refreshing appraisal of a renewed interest in Jewish themes and biblical narratives on the part of Israeli artists.

The exhibition does not shy from drawing on earlier Israeli examples of this subject, notably Able Pann’s 1923 lithograph of the first man, Adam, “And breathed life into his nostrils the breath of life.” Primeval man is seen sitting in profile, a squatting muscular male figure under a starlit sky. A yellow shaft of light pierces the image, illuminating Adam’s upturned face, seeming to bring him to life. While hardly an earth shattering image this work is unusual for Pann whose depictions of biblical characters are normally illustrations of exotic local Arab-Bedouins. Here the image has a Blake-like intensity, a primitive power that evokes the elevation of the bestial into the human.

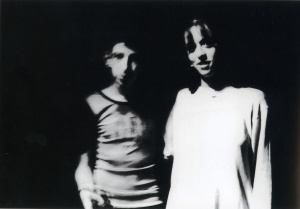

Ilit Azoulay’s Amnon and Tamar (2001) totally ignores the metaphorical, peering instead into the perceptual aspect of the subject. Her 3′ X 5′ black and white photograph of a teenage girl and boy is at first innocent enough. The boy on the left, out of focus, is spectral, a hesitant image staring out into the middle distance. In contrast “Tamar” is clad in white and confronts the viewer with an innocent yet straightforward smile, her arm around the youthful Amnon. At first seeming to be a contemporary snapshot, the biblical allusion to a tale of deceit, rape, cruelty and vengence slowly dawns on us as we remember the narrative in 2 Samuel 13:1-18.

The exhibition moves from biblical narrative to postmodern halachic discourse seamlessly. Six hundred and thirteen yahrzeit candles are arranged atop one another on a simple white table in Dov Abramson’s 2003 Ner Mitzvah. Computer generated labels painstakingly summarize the Sefer ha Chinuk, the 14th century compilation of Jewish law, producing a schematic label that identifies each biblical mitzvah, cites it’s location in the Torah and defines it according to its applicable number, type, location, penalty for transgression and gender affected. On the back of the yahrzeit candle label a portion of the Chinuk’s text is quoted.

This highly engaging conceptual work effectively compresses the structure of the halachic universe into an intelligible symbol visible at one glance. It conceptually invites compliance from the viewer, imagining the lighting of the candle, i.e. performing the commandment, thus fulfilling the verse that says; “For the commandment is a lamp and the Torah is a light” (Proverbs 6:23; explained in Megillah 16b). Simultaneously the work exposes the vulnerabilities of the halachic system; the tendency for rote performance and hollow symbols, by creating mechanically reproduced labels, each a carbon copy of the next except for textual variations. Abramson’s work warns against mechanically produced mitzvot, mechanically lived Jewish lives. The haunting experience of Ner Mitzvah easily overcomes the absence of aesthetics.

Continuing in the conceptual mode, light is now transformed from a positive concept into a medium of death. In Military Outpost #2 (2002-2003) by Shai Azoulay orange tracer lines pierce the darkness outside an outpost on the Lebanese border. Barely visible buildings, foliage and distant lights of habitation form the backdrop for the violence of rifle fire, bullets streaking through the night on a deadly mission. The two canvases set inches apart bespeak a light that seeks a deadly connection between aggressor and victim. Death becomes abstracted as pure line on the flat picture plane against the naturalism that paradoxically contains it.

“Bereshit” Synagogue (1997) by Belu Simion Fainaru pushes the conceptual to its most concrete limit. A 6′ by 3′ table, its black top filled with three inches of water forming a perfect reflecting pool, acts as the base for a stone structure marooned in the center. The stubby casket shaped box ironically represents a synagogue and is sliced on four sides by the six letters of alef, beit, gimmel, dalet, hay and vav. The roof is pierced with a shin. Each of the letters, incised backwards, shines forth via a mysterious interior light. The symbolism of the seven days of creation, capped by the shin of Shabbos, can only be “read” properly from the inside of the “synagogue” vessel. The problem is that we cannot get inside to properly understand the text, either because we are physically too large (trapped by our bodies) or because the synagogue is surrounded by a watery moat. In any event the proper appreciation of Genesis is constantly frustrated, reflecting our modern condition.

As intellectually engaging as these works are, Angel’s Blood by Eran Erlich captures the imagination unlike any other work here. A piece of translucent Plexiglas is etched from the rear, depicting the circulation system of an angel/man standing legs slightly apart and palms out. The major arteries and veins are traced as the light catches them illuminated from above and below. The complex metaphor of light as life-blood within a physical body (with enormous wings no less) begins to capture, indeed depict, the very spirituality within us all. Additionally the iconoclastic notion of angels as terrestrial beings who act as humans, performing missions and heavenly tasks returns to contemporary dialogue the forbidden notion of Divine intervention in banal affairs. Seldom has contemporary art tackled spirituality with as much fearlessness.

The light that this exhibition casts on contemporary Israeli art is promising. The Adi Foundation continues to foster the connection between Jewish ideas and contemporary cultural expression. The very quality and creativity of many of these works breeds hope that finally a uniquely Jewish approach to the world is finding its expression in contemporary Israeli art.