Life on the Book: Constructions by Gad Almaliah

The Land of Israel was possessed by a terrible drought and prayer was necessary. “It happened that the people said to Honi the Circle Drawer, pray for rain to fall…He prayed and no rain fell. What did he do? He drew a circle and stood within it and exclaimed, Master of the Universe, thy children have turned to me because they believe me to be as a member of thy household; I swear by Thy great Name that I will not move from here until Thou has mercy upon Thy children. Rain then began to drip, and thereupon he exclaimed: It is not for this that I have prayed but for rain [to fill] cisterns, ditches and caves. The rain then began to come down with great force, and thereupon he exclaimed, it is not for this that I have prayed but for rain of benevolence, blessing and bounty. Rain then fell in the normal way…” (Taanis 3:8).

In Boston there is an artist, Gad Almaliah, who has created a series of six constructions of open books. He manipulates second hand books into facsimiles of Hebrew books, using carefully generated computer images to avoid any desecration of holy words. Each construction is contained in a box twenty inches square with one side open for viewing. The artist says they are deeply personal pieces about “the future of Jewish life, culture and its survival.”

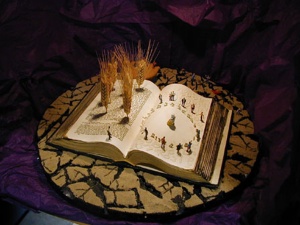

Certainly Jewish survival is the subject of Honi The Circle Drawer. In the first construction, a kneeling Honi is surrounded by a circle of Hebrew letters and twelve figures of contemporary people encircle the circle and look on in anticipation. Honi’s audience stands on ground made up of arbitrary letters. The opposite page is from the Midrash Rabbah and seven gigantic sheaves of wheat sprout through its pages. The open book is set on a circle of earth deeply fissured and cracked by drought.

It seems the artist is telling us that a tzaddik like Honi is fundamentally distinct from us, the Jewish people. Yet he is within our circle, using our language and arguing our case before the True Judge. Imagination, determination (even chutzpah) and piety like his can make the midrashic text blossom with very real nourishment.

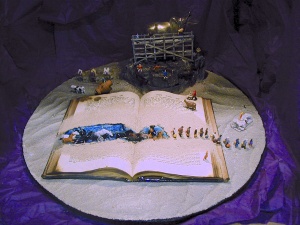

The pages of the next book split to consume Pharaoh’s army and horse drawn chariots while the Children of Israel march calmly in single file, suitcases in hand away from the chaos behind them. This construction entitled, We Were All Slaves, again using the Midrash Rabbah as the foundation text, connects the splitting of the sea with the Golden Calf, here seen as a massive bull surrounded by a scaffold being fashioned by the Jews. The way that Almaliah combines these two events, making them feel simultaneously contemporary and Biblical is only the beginning of his achievement. Viewing his sculpture, we are forced to confront the miracle of God’s salvation of the Jewish people and our subsequent ability to ignore it with a shocking lack of faith as exemplified by the Golden Calf.

Gad Almaliah is a Jerusalem born graphic designer not known for his sculpture. He is a graduate of Bezalel Academy and has worked for many years in graphic design for the Israel Army, a Tel Aviv advertising firm, a Mexican university and now owner of The Design Lab, based in Boston. Unlike his normal production of Judaica, hand embossed metalwork ketubot, poster, print and stamp designs, this series of constructions are not for sale. Rather he hopes them to become a traveling educational exhibition.

Two of his pieces in the Life on the Book series are too personal for me to penetrate. Untitled presents us with a hole burned in the center of a text filled with babies’ bodies opposite an enormous quarter dollar. The Rule of Law, while somewhat more approachable, still is mired in obvious symbols like a ruler, a courthouse and US currency. Only when Almaliah sticks to Jewish and Biblical subjects that his works reaches its full potential of complexity and insight.

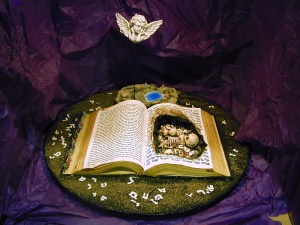

White Bones confronts Ezekiel’s Vision of the Valley of Dry Bones in the very body of the Hebrew text. The page has been scorched open to reveal a grotesque skeleton amidst other bones and discarded Hebrew letters. A plaster-cast angel floats beatifically in the purple dark sky above as the English translation on the opposing page confirms the subject. The unease felt with this image deepens as we notice behind the book a jarring scene of modern vacationers around a little pond. The left side of the book is lined with contemporary figures marching determinedly as the surrounding ground is littered with more discarded Hebrew letters. The ancient prophecy of the resurrection of the Jewish people is here cast as a contemporary question. Can this text and these bones live now? Are our lives, now largely comfortable and secure, still subject to this vision of Jewish renewal? While the bones may be reconstituted in our world, does the text live for us?

The last work in the series, Graveyard, affords us a view of a bifurcated world. Again twelve contemporary figures stand on a page of bas-relief letters. All but one are separated from the graveyard by a solid brick wall. The graveyard contains the tombstones of twenty-four sages, from Rashi to the Baal ha Tanya and including 20th century masters. Behind this tableau morte an ancient tome lies half buried in the sand alongside Greek ruins. Almaliah’s pessimism about penetrating the wall separating us from our spiritual sources reflects a secularist’s frustration at approaching Jewish knowledge from the outside, even with the tools of Modern Hebrew. Still there is hope, as witnessed by the singular figure on the graveyard side of the wall and the chorus of women and children adjacent to the sages. Again and again Gad Almaliah’s work questions the pressing issues of Jewish life, culture and its survival by examining our connections of language, holy texts and buried traditions.

There are droughts and we pray. Simeon ben Shetah criticizing Honi the Circle Drawer because he troubles God about rain many times then said; “but what can I do to you who importunes God and He accedes to your request as a son importunes his father and he accedes to his request.” We are certain that the True Judge hears and will have mercy on His children.

Gad Almaliah can be reached concerning Life on the Book at thedesignlaboston.com

Published in The Jewish Press