Chava Roth’s Meanings

Pleasure and Meaning. In the visual arts they are equally essential. The pleasure of looking at an object, its contours, colors, texture and subsequent visual excitement is fundamental to engaging the viewer. Lacking visual enjoyment and complexity a painting, drawing or print will quickly lose the interest of the viewer and they will move on to a more rewarding visual experience. And a rewarding visual experience is the foundation of ascertaining the meaning of a work of visual art.

Whatever the meaning, it must unfold slowly, though the pleasure of following complexity of composition, color and surface. If you get it instantly, you are looking at an illustration, simply a superficial visual sign, not a work of art. Chava Roth’s current exhibition of paintings and watercolors at the Chassidic Art Institute offer us both pleasure and meaning in decidedly unexpected ways.

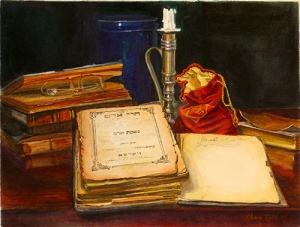

Roth’s primary métier is the painting of Jewish still lifes as we extensively explored in the January 2001 review in the Jewish Press. She continues to show these rarified gems of tradition and nostalgia. Centered on the symbols of Jewish scholarship and learning, her compositions have if anything become stronger. Still Life (Chaiye Adom) is rooted in an open sefer, its pages frayed in a binding that has long since given up holding anything together. The covers simply form a container for a mass of loose pages, ostensibly perused year in and out. Rising from the spine of the sefer is a silver candlestick with a handle. At the top the mostly burnt candle is extinguished. To the right a crumpled red tefillin bag stands guard over the surrounding books, each well used and worn. The absent scholar’s eyeglasses mark the place in one of the books. The simplicity of the triangular composition with the candle at the apex creates a deceptively nostalgic image. While we first think this painting evokes timeless Torah values of learning and piety, at second glance something very different emerges. We notice that the picturesque sefer is so tattered that it is practically unusable. Additionally the tefillinbag is suggestively open, as if its prize contents have been carelessly put away, tossed on the littered tabletop. Finally the unlit candle stops us cold. Here in the apogee of the composition, the place where our eye is inextricably led, there is no flame, no light, perhaps no future. Roth’s lush rendering of frayed paper and bindings invites us to the pleasure of uncovering the complexity of her meanings.

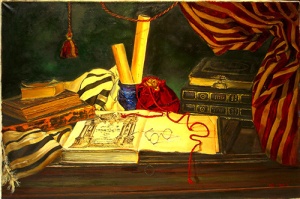

Kesuvos, another Jewish still life, is similarly based on a triangular composition. But here the effect is altogether different. The primacy of learning, expressed by the open gemara surrounded by other seforim and two volumes of the Minchas Chinuk, is here made more complex by the intrusion of two distinct mitzvos, tallis and tefillin. The same old fashioned red tefillin bag (here mostly closed) is joined by a tallis hastily removed and put on the table, its stark black and white pattern contrasting with the warm tones of the books. The red drawstring of the tefillin bag symbolically embraces the open gemara, further integrating learning and the performance of mitzvos. Two mysterious scrolls in a blue glass container center the composition that is framed by a dramatic striped drapery swag, swept back to uncover the tableau. The strong central lighting on the objects and the drapery curtain create a theatrical effect, a kind of visual “Behold!” This pictorial device, frequently seen in eighteenth century still lifes, makes the painting an affirmation of traditional Judaism.

Roth is also showing a number of Jewish genre subjects, all taken from scenes of Jerusalem. Many are of Chassidim walking the streets and alleys of Zichron Moshe clad in streimel and tallis. These picturesque images, usually drawn from multiple photographs she has taken and then combined as a visual resource for her paintings, show a consummate interest in the details of everyday life in Jerusalem. One outstanding example is Four Soldiers. Two white stockinged Chassidim trudge up a narrow street in the old city parallel to two IDF soldiers on patrol, automatic rifles slung across their backs. While the message that both military might and religious piety are necessary for the Jewish state is quickly ascertained, the complexity of composition encourages further scrutiny. Two arches, each slightly different, join the pairs. The green khakis contrast just enough with the black and white traditional clothing to maintain separation. In fact the tension-filled contrasts, at first uniting and then separating, emerge as a running leitmotif that animates the image. The soldiers are in sunlight and yet directly under an awning while the opposite is true of the Chassidim, in a well-lit shadow open to the sky above. Even though both pairs are seen from behind, their body language indicates they are equally engrossed in their private worlds, almost oblivious of each other. Together and yet separate they guard the city.

It is perhaps the fresh perspective on Jewish life that animates Roth’s best work, making us reassess the familiar. Men at the Wall is easily the most intriguing painting in the show for this very reason. We are initially seduced by the stock image of pious Jews praying at the Western Wall. They are supplicating, pleading, saying Tehillim and confiding to God their innermost needs. Emerging from the afternoon shadows the four primary figures, each attired in a long bechesheh and black hat, face the Wall. Above them the familiar foliage spouts from the crevices in the ancient stones. Superficially, a totally predictable image. But it is in the details that a much more complex and emotional meaning emerges.

Playing again on contrasts, Roth has set up two opposing movements that express an optimistic understanding of what actually occurs during a visit to the Wall. The men face in, implore into what appears to be unyielding stone in an ordered assault on Divine distance. In response the Wall blooms, the foliage bursts out, practically erupting in green, yellow and white blossoms showering the pious with symbolic verdant sustenance. A dialogue has been established affirming the faith that God indeed answers prayers. Anchoring this visual conversation is the red velvet covered bimah in the lower left, at once representing Torah and, its aron-like shape in line with the shadowed wall, death. One third of the image reminds of mortality while the majority is a dialogue that establishes meaning in Jewish lives and gives hope for the future.

Through the pleasure of picture making Chava Roth forces us to take notice of unexpected meanings and observations that slowly but surely emerge from the everyday. The pleasure of the excursion to the prize of meaning is well worth the trip.