The Painted Shul

“Stylistic unity is blasphemy in synagogue decoration. Such unity becomes an act of hubris on the part of the artist,” declares artist Archie Rand, explaining the aesthetics of the wildly diverse murals at the B’nai Yosef synagogue in Brooklyn. His unique artistic and theological vision arises out of a volatile mix of late Modernist aesthetics known as Postmodernism, Rand’s fascination with esoteric religious symbolism and his weakness for Pop Art irreverence.

Postmodernism, though notoriously elusive to define, began to distinguish itself in the waning days of the New York School of Abstract Expressionism in the late fifties and sixties. By the time Pop Art, Op Art and Conceptualism had effloresced in the sixties it had become increasingly obvious that twentieth century Modernism was breaking apart into a multiplicity of movements fundamentally different from what had preceded it. Postmodernism in the visual arts was characterized by an increase in eclecticism of style, multiplication of self-referential meanings and frequent internal contradictions in images.

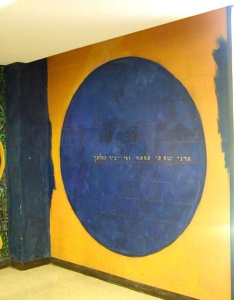

In the rear corner of the prayer hall we see a blue circle mandala containing the introductory meditation to every Jewish prayer; “My Lord, open my lips, that my mouth may declare Your Praise.” This use of the mandala, a Tibetan Buddhist meditational device, to frame a Jewish meditation combines an Eastern religious motif with a specifically Western text. The adjacent rear wall is dominated by the injunction of Yehudah ben Tema in the Ethics of the Fathers; “Be bold as a leopard, light as an eagle, swift as a deer, and strong as a lion, to carry out the will of your Father in Heaven” found in the well known Ethics of Our Fathers. The text is illustrated with animals straight out of National Geographic and a postcard image of a cedar of Lebanon. The clash between the Buddhist inspired spirituality of the mandala and Pop Art animals could not be greater; except for the tension provided by the next panel, a faux monochromatic De Kooning pictorial riff that contains a plaque bearing the cardinal declaration of Jewish faith, Shema Yisroel.

Standing in the rear of the synagogue and experiencing these shifts from prayer to wisdom literature and finally to a proclamation of faith, each out of its normative sequence, is a Postmodernist aesthetic experience at its core. Rand does not let the viewer rest or move in an ordinary narrative sense from panel to panel. Rather he forces us to jump from one disjunctive subject and style to the next constantly readjusting our understanding with each image.

Adding yet another layer of complexity of these paintings Rand utilizes his yeshiva studies to explore the dark corners of esoteric Judaism. Most Orthodox Jews go about their daily lives, earning a living and raising a family, without much thought to “the End of Days.” Rand devotes entire sections of his mural to pictorial explications of this type of speculation.

The entire right wall, dominated by sky blues and puffy cloud whites, evokes a symbolic Messianic age, classically understood as the End of Days. A fiery Third Temple descending from the heavenly realms is followed by a suspended wedding canopy depicting the Earth’s surface hovering over the original desert Tabernacle. Finally we see a contemporary view of the impressive walls of the old city of Jerusalem. It is all here, past, present and future sites of holiness as time collapses into a mystical vision.

In the women’s section in the balcony upstairs the theme shifts to the cycle of yearly holidays as seen in esoteric and mystical terms. Rosh Hashanah is evoked in images of the Book of Jonah that is read on that holiday with a foundering ancient ship and a mysterious serpentine cord slashing across the watery image. In a cascade of disparate images and styles, holiday follows holiday. An extensive treatment of the Passover holiday dominates the back wall with its myriad symbols in a thicket of abstraction. Finally, at the extreme right side of the long balcony the Tomb of Rachel is seen in night vision through a fantastic decorative archway. Rand uses three-dimensional objects in conjunction with trompe l’oeil arches to confuse the viewer as he mixes reality and the painted image. This well-known image of Rachel’s Tomb recalls the passage in Jeremiah that tells of the matriarch Rachel wailing for her children, the dispersed Jewish people. From the opposite side of the synagogue you can see that this panel is directly over the depiction of the End of Days.

Rand continued to work on relentlessly. With the completion of each new panel, the images slowly settled into the visual consciousness of the congregation. Congregants noticed that the mystical Magen David, which echoes Syrian carpet designs, was ingeniously created without any triangular patterns. Someone explained that the artist was especially careful not to allow lines to intersect to form a cross, and the congregants nodded in approval. A dark brooding panel surrounded by thick ropes puzzled everyone until word got around that the artist meant for the ropes to remind them of the ropes that Abraham used to bind his son Isaac. A text fragment of the famous Avinu Malkeinu prayer; “Do this for the sake of those who were killed and burned…” soon appeared against the dark abstraction. This plaintive prayer is said on fast days and especially during the ten days of repentance between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. The passage of the binding of Isaac is read on Rosh Hashanah. In the congregation’s mind it was all coming together.

The opposition to the murals gradually melted away as more congregants recognized symbols, texts and images that connected with their own Judaism. Slowly the murals became a source of local pride, so much so that they now started calling their synagogue, “The Painted Shul.”

Now completed, the murals in the main sanctuary are a synthesis of Postmodern aesthetics, two thousand years of rabbinic interpretation and Sephardi sensibility. What Archie Rand produced from the original confrontation with the rabbis was an amazing mix of symbols, images and aesthetic riffs that is Postmodern at its core. While normally singular images would dominate and focus an expansive work like this, here the real subject is the process of art in a sacred space. Rand’s vision of that process is fluid, contradictory and ultimately, non-figurative. It is constantly concerned with denying the possibility of idolatry by removing focus. In the overall scheme of the space the images that do emerge are fleeting. Each aesthetic experience is localized in disharmony with adjacent panels. It is as if Rand, both anticipating and reacting to the critical rabbinic gaze of this strict Syrian community, has found a way to be simultaneously symbolic, representational and abstract in a contentious observance of the Second Commandment.

Published in The Jewish Press