Contemporary Jewish Art

We have documented eighteen hundred years of Jewish Art production in the preceding five sections of the Jewish Art Primer. These artworks are rich and varied creative expressions of Jewish life found in mosaics, murals, manuscripts, illustrated Haggadahs, micrography, papercuts, graphic arts and paintings. Contemporary Jewish Art, easily as vital, may be the most prolific in all of Jewish history. It is characterized by a number of different modes of Jewish artistic production: Traditional Judaica; Biblical art, Diaspora / Postmodern art and Holocaust art (which we examined in Part V).

Traditional Judaica

Not surprisingly Judaica production continues unabated. All conceivable forms of Jewish ritual objects continue to be fashioned by artists and artisans. The American Guild of Judaic Art (jewishart.org) boasts over two hundred members. The Jewish Museum, Yeshiva University Museum and Hebrew Union Collage–Jewish Institute of Religion Museum (all in New York City), along with many Judaica Museums and stores throughout the country periodically exhibit a vast array of Judaica. Many objects follow patterns first created in the eighteenth and nineteenth century while just as many reflect more contemporary designs. The Bezalel School in Jerusalem is a major center of contemporary Judaic design as was the Jewish Museum in the 1970’s under the influence of Ludwig Wolpert.

Biblical Art

Contemporary Jewish Art utilizing the Torah as its subject matter is created less frequently than might be expected. The vast richness of biblical narratives along with two thousand years of commentary and midrashim has yet to attract more than a few artists to mine its treasures. This artistic hesitation may be the result of a misplaced sense that these subjects are simply too sacred to adequately approach. This exposes a sad ignorance of Jewish art history recounted here. It is as if many contemporary Jewish artists have bifurcated lives. The Torah and its literature are shut up in the religion box, while their artistic lives are segregated in their studio. The two interests seldom talk to one another. Janet Shafner, John Bradford and Richard McBee (this writer) are three artists who are the exceptions to this trend and have devoted much of their work to the Biblical narratives.

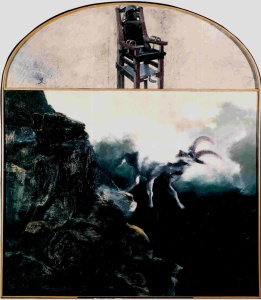

Janet Shafner has worked for close to twenty years juxtaposing the Talmudic and the biblical in dramatic paintings that range from Adam and Eve to Mordechai and Esther. Among her many paintings Azazel The Scapegoat (1994) provides a typically complex commentary on a piece of Torah. During the Yom Kippur service the hapless goat sent to Azazel is seen tumbling down the rocky hillside, looking back at his executioner just before he is shattered to death by the fall. His gaze directs us to the lunette above that contains the solitary image of an electric chair. The goat sent to Azazel carries the sins of Israel into the wilderness and through this avodah we find atonement for our sins against God but not against our fellow man. But those human sins must be paid for by ourselves, through apology, repayment, punishment or even death. Execution as punishment, execution as atonement, execution as vengeance. Shafner’s painting speaks of the terrible consequences of sin.

The unadulterated essence of the biblical narrative is John Bradford’s quest as he paints the archetypical stories all their starkness and simplicity. His modernism shapes the narrative images into an elemental distillation of the Torah that, through the act of its creation, find fresh insights into the history and development of monotheism. Jacob and the Angel (2003) at first glance seems to be a drawing on canvas until one realizes the monumental size, over 6 x 8 feet, and tremendous substance of the surface, patiently built up over months of pictorial struggle that were fundamental to find just the right image, pared down to all that is necessary to convey the mysterious narrative. What exactly was the nature of Jacob’s struggle and how did he finally prevail? The stooped figure of Jacob is fruitlessly striding forward, caught in the embrace of a flying figure, with one of its feet attached to the upper edge of the canvas. The painting tells us that the struggle will not end with dawn and in fact will characterize all of Jacob’s descendants throughout time. Our relationship with the Divine is what identifies us as Israel.

For the last 30 years my artwork has been devoted to the biblical narrative, concentrating on the Akeidah, Jacob, Joseph, Moses, David, Esther and Ruth. David Dancing Alone (1999) turns the traditional narrative into a meditation on the artist’s service to God. David dances totally absorbed in religious ecstasy, paradoxically alone and ignored by the crowd at the right while subject to the scorn of his wife Michal overlooking the scene in the upper left. The artist must serve Heaven using the tools that God gave him.

Diaspora Art / Postmodern

The twentieth century was witness to yet another cultural revolution starting sometime in the late sixties and early seventies. Where Modernism is confident, iconoclastic, pure, high art, serious and prone to grand theory; postmodernism is questioning, kitsch obsessed, derivative, irreverent, ironic and subjectively non-committal. For Jewish Art it represents commentary over text, questioning over received truth.

R.B. Kitaj, one of the best known contemporary Jewish artists, is obsessed with the role of the Jew in the Diaspora. He has written two Diasporist Manifestos (1989 & 2005), rambling self-indulgent documents that explore the relationship of the Jew and the Jewish artist to modern society. “JEWISH DIASPORIST ART IS AVANT-GARDE (a Cosmopolitan trope I happen to like). This new art is often TABOO in art circles, the way avant-garde used to be.” (Meaning that the mainstream art establishment refuses to recognize contemporary Jewish Art.)

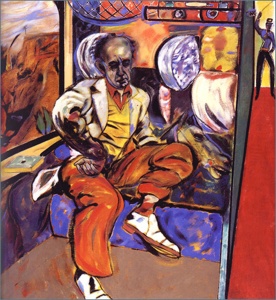

A painting from his March 2005 Marlborough Gallery exhibition How to Reach 72 in a Jewish Art, explicates the notion of Diasporist Art. Three Famous Jews (2004) purportedly represents the classic formulations of the Ego, Id and Superego as three bold figures. Freud and his intellectual creations are celebrated as honored Jewish personages. Kitaj explores the experience of exile, especially in paintings like The Jewish Rider (1985). His image of a contemporary well-dressed Jew is based on the famous mounted figure in Rembrandt’s Polish Rider in the Frick Museum. Here instead of a horse the elegant traveler sits in a railway compartment, passing a distant landscape punctuated with a cross and smoking chimney. The all too familiar association of trains, Jews and exterminations turns the Rembrandt quote on its head to comment on the Wandering Jew continually exposed to danger and uncertainty.

One Jewish artist who constantly throws caution to the winds is Archie Rand. His latest ambitious series, The 613, presents one painting for each of the biblical mitzvas. He arrives at the each image by a counter-intuitive methodology; locating pop, comic, art history and photographic images that appeal to him and then finding a correspondence to the commandment at hand. Through his visual intelligence and considerable sensitivity to Jewish knowledge he frequently uncovers a new twist in the meanings already assumed. A perfect example of this is the 1992 painting of the Akeidah in his Sixty Paintings from the Bible. These images are taken from a set of seventeenth century engravings by the Christian artist Matthaeus Merian. Rand appropriates the images as a mere scaffolding to “reassess the Tanach, get past the standard English translation and find the ‘punch’ of the original Hebrew.” The comic book technique (invented and dominated by Jewish artists) allows the use of the word balloon, bold letters, underlining and italics, to simultaneously emphasize text and image and comment on both. We see an angel interrupting Abraham about to slaughter his son. Abraham looks up shouting “I’M HERE!” This response, textually true and yet visually impatient and impertinent, implies a fundamental challenge to God’s concept of a test.

A legion of other contemporary Jewish artists demands comment but here a partial list must suffice. Tobi Kahn’s ritual objects and mysterious paintings demand Jewish sensitivity without admitting their Jewish content; Lynne Russell’s paintings over photographs reinterpret contemporary religious Jewish life; Miriam Beerman welds the 10 plagues into the woes of our century; Grisha Bruskin’s kabbalah infused mythologies confound interpretation as Talmudic paradoxes; the traveling exhibition “Women of the Book” demands a feminist perspective to Jewish life; Ita Aber wields fabric and objects to uncover the uncertainties of gender relations in ritual objects and jewelry; Itshak Holtz documents the genre delights of Israeli Haredi life.

It should go without saying that this Jewish Art Primer is not meant to be an exhaustive study of Jewish Art. It is simply an introduction to some of the visual culture of the Jews. By necessity of limited space it has excluded many artists and artworks and modes of expression (architecture, photography, music, textiles, decorative arts, genre and primitive painting). For these omissions, especially for contemporary artists, I apologize

We live in a time when notions of “Jewish Art” are persistently denied. I hope I have shown that not only is there a long history of Jewish Art but also a vibrant contemporary group of artists who make Jewish Art, no matter whether they or their critics accept the term or not. This assertion is important because this thing I call Jewish Art is a part of the expression of the emerging culture of modern Jews. In an age of rampant assimilation and in the devastating shadow of the Holocaust, the Jewish people are growing strong culturally and religiously in a largely secure Diaspora and vibrant Jewish state. Our age demands a Jewish culture to stand next to our many other achievements. The artists are creating it, it is up to the audience to see it. The challenge is in your hands.