Masterpieces from the Bodleian Library

In the eyes of the ram lies the artist’s commentary on the Rosh HaShanah piyyut; “The King Girded with Strength.” From the Tripartite Mahzor (German 14th century), this illumination simultaneously echoes the piyyut’s praise of God’s awesome power and expresses the terror of actually being a sacrifice to God. The ram is but a reflection of Isaac. It is all in the eyes.

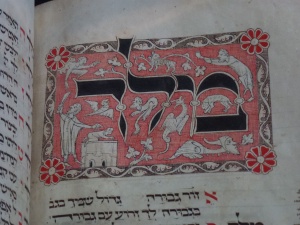

Nearby another German Mahzor (14th century) is open to the same piyyut, here illuminated in a simpler manner: Isaac is on the altar ready to be slaughtered, Abraham heeds the angel and a collection of medieval grotesques, animals and men react to the horrible event. God’s strength is reflected in the ability to summon obedience to a deadly command.

Two very different interpretations of the same piyyut probably created within decades of one another. And are both shown at the Jewish Museum’s Crossing Borders, an exhibition of medieval manuscripts from the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford. This extraordinary exhibition presents the vibrant cross-cultural influences in the creation of medieval Hebrew manuscripts in the context of both Christian and Islamic cultural production. Additionally it explores the fascinating relationship between text and image in illuminated manuscripts.

The exhibition opens with three radically different manuscripts. A Hebrew Bible from Tudela (or Soria), Spain by artist and scribe Joshua ibn Gaon of Soria, (c.1300) displays the overwhelming Islamic decorative influence in Spain at the time. The facing carpet pages brilliantly shows interlocking abstract designs, one framed by a textual border, the other a heavy gold-leaf frame.

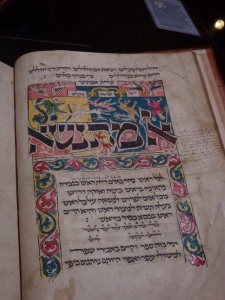

Next is the earliest known dated and illustrated Mahzor (1257-1258) from Germany open to the page with the special piyyut for Shabbos Shekalim. The initial word panel is illuminated with an intriguing stag hunt scene featuring the two hunters whose helmets cover their faces. This sensitivity about depicting the human face is seen throughout this Mahzor and likely reflects a lingering concern over the second commandment that flourished in southern Germany in the 1230’s. But most surprisingly is the fact that the whole charming scene is depicted upside down! One reason given in the original catalogue essay by Eva Frojmovic for this singular depiction has been attributed to a Christian artist’s mistake, being unable to read the Hebrew text, and assumed it worked better upside down with the image centered at the bottom of the page. The curator of the Jewish Museum installation, Claudia Nahson, more plausibly explains that this upside down scene may be a reflection that this piyyut is recited right before Purim, when everything is “turned upside down,” especially in the narrative of the oppressed and hunted Jews.

Finally, the “Even HaEzer” (1438) from the Arba’ah Turim of Jacob ben Asher (the Tur) reveals sumptuous early Italian Renaissance manuscript illuminations. Gold leaf abounds amid peacocks, exotic birds and fantastic creatures surround the text “It is not good for man to be alone…” echoing the depiction of the creation of Eve in the Garden of Eden. Adam lies asleep as a winged Creator, complete with halo, kneels next to him, about to extract Eve from his side. On the right we see Adam and Eve poised before the forbidden tree and the tempting snake. The extremely unusual depiction of the Deity in a Hebrew manuscript reflects the highly acculturated nature of the Italian Jewish community almost certainly working with a Christian artist.

In these intriguing examples one can treat the visual as decorative and incidental to the text, thereby discounting the inherent and potentially disruptive meaning of the images. Or one can attempt to integrate image and text and see them in creative relationship, effectively arriving at a new meaning of both text and image. Considering the enormous cost of illuminating manuscripts, the competition with surrounding non-Jewish elites, and the fact that manuscripts with such subversive images continued to be prized and used, I cannot believe for a moment such images were anything but intentional.

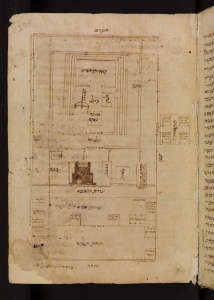

One of the most exciting manuscripts here is the Rambam’s Commentary on the Mishnah Nezikim and Kiddushin that is open to a diagram of the Temple facing the text. It is thought to be an autograph copy from 1168. While diagrams in the text of the Mishnah are not unheard of, nonetheless to see the Rambam’s autograph text next to an image used to help explicate the actual layout of the Temple is a revelation. Everything about the Rambam summons the primacy of text and intellectual conceptualization. And yet here the Rambam does a drawing to explain the text!

This and many other manuscripts in this section validate how integrated text and image was in the Middle Ages. We see the visual approximations Ezekiel’s vision of the Temple in the commentary on the Bible by Nicholas of Lyra (Paris 1400), another by Richard of St Victor, as well as a Hebrew version of Rashi on Ezekiel. Additionally there are visual explorations of the exact form of the Temple Menorah and the arrangement of the tribal camps in the wilderness.

The exhibition is wonderfully curated into clear sections and subsections. Within the sphere of Islamic Influence is a Christian Bible in Arabic and a Quran displaying superb illuminated carpet pages. Nonetheless, in this section the Kennicott Bible overwhelms the surrounding manuscripts. Created in Corunna, Spain in 1476, it is a masterpiece of Jewish illumination combining Islamic and Christian motifs. Notably bereft of narrative illustration, the decorative elements are breathtaking. Dogs chasing hares with myriads of birds, foliage, gold leaf and Islamic arches, the text is constantly surrounded by visual agitation and stimulation. Delicate pinks, earth colors and vibrant blues dominate with sensitive touches of gold leaf. As beautiful as the two open facing pages are, one hungers to explore the rest of the 922 page manuscript. And the Jewish Museum has responded by creating a scanned version of the entire manuscript visible in the gallery and online. The Sefer Mikhol, a grammatical treatise that is included in this Tanach, is a masterpiece of Islamic-style illumination with page after page of different architectural motifs surrounding the text. All of the books of Tanach are punctuated with decorative grotesques tantalizingly echoing the narrative structure. This manuscript alone could consume a visitor for many hours.

“How does Hebrew book production reflect a relationship with the non-Jewish world?” The Bodleian catalogue answers that it was close, even, very close. In the words of Piet van Boxel: “they display coexistence, cultural affinity as well as practical cooperation between Jews and their non-Jewish neighbors.” The complexity of Jewish interaction with surrounding cultures is well explored here as well as the singular nature of Jewish manuscripts. The catalogue contrasts Latin manuscript production of the codex in the 2nd CE (i.e. a book as opposed to a scroll) with the Hebrew adoption of the codex in the 9th century. But once adopted, the Jews created codex manuscripts privately commissioned for public use that became luxury objects conveying social status and emulating the aristocratic wealth of non-Jews.

The exhibition Crossing Borders depicts a medieval Jewish world in which indeed many borders are crossed. While at times these images and cultural norms may make us uneasy, upon closer examination they inevitably tell us something new and revealing about our heritage and unique vision. They also point to a cultural attitude we could well learn from. The polyglot medieval culture these Jews found themselves in is in many ways terribly familiar to our own world. And in their engagement with this alien and yet fascinating culture, they made some of the great masterpieces of Jewish visual culture.

Crossing Borders: Masterpieces from the Bodleian Library

Jewish Museum: 1109 Fifth Avenue @ 92nd Street

www.thejewishmuseum.org