At The Library Of The Jewish Theological Seminary: The Word Became an Image

The visual image is not a problem in Judaism. We have countless examples of images and representations of Jewish subjects and ideas done by pious Jews throughout the centuries, whether as ancient synagogue mosaics, illuminated manuscripts, synagogue wall decorations or paintings. But, in spite of this evidence, there is a parallel Jewish sensitivity to images. We understand, in light of the Second Commandment, that images may be fraught with accusations of idolatry and blasphemy. We are exquisitely aware of this tension concerning images of whenever we express ourselves visually. Out of exactly that tension Jews have championed a unique art form that by its very nature attempts to resolve any residual issue with images.

Micrography resolves the iconographic problem by synthesis. This art form takes words and specifically holy words, and creates images by the shaping of words written small. In doing so, this ancient art form can, in Jewish terms, become its own opposite. The dangerous image is made kosher with the safe and holy word.

Micrography, The Hebrew Word as Art is a small but intense exhibition at the Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary that explores this fascinating art form. The exhibition provides us with examples of two kinds of micrography. The first kind, decorative micrography is devoted to hiddur mitzvah, creating purely decorative designs as borders or as entire pages of abstract decoration. The second type, pictorial micrography, creates complex representational images that actually add meaning to the text.

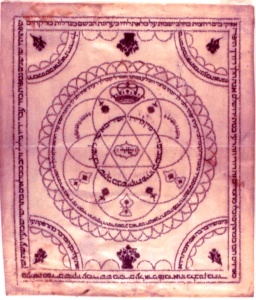

Shir ha Shirim is an example of decorative micrography that was created by Baruch ben Shemariah of Brisk in Lithuania in 1824. It is a tour-de-force of the art of micrography, recalling the carpet pages of mesorah from the tenth century codices that are the first examples of this Jewish art form. With the exception of the crown and the bouquets of flowers along the edges, the entire design is created by minuscule lettering of the Song of Songs. Line flows into line and then chapter into chapter in a beautiful, delicate and elegant presentation piece probably created as a wedding gift. The tumble of words creates an object that only occasionally relates to the work of Solomon. When the letters are used larger, such as in the inner circle (the beginning of the text) and along the outer edges and corners, the text leaps alive. In the rest of the design the text is too small to read without a magnifying glass and therefore becomes a decorative object that murmurs the holy words softly.

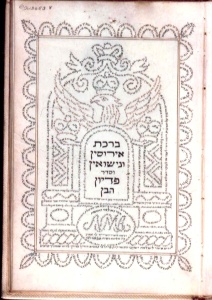

A transition between the decorative and pictorial is the Brochos for Betrothal and Marriage and Pidyon ha Ben by Dayyan Aaron ben Yehudah Leib of Lissa, done in London in 1849. Here the artist-scribe includes the Song of Songs along with the blessings that will consummate the love between a man and a woman. The decorative border surrounds a fantastic architectural motif that encloses a crowned eagle, all evoked in diminutive text. The majority of this image is delightful decoration, an adornment to the blessings for a bride and groom. Nevertheless, the inclusion of the image of a crowned eagle gives the imprimatur of official royal recognition of the marriage and a nod to the legitimate authority of the kingdom.

Micrography arose as an art form sometime in the tenth century in Egypt and the Land of Israel, heavily influenced by the surrounding Islamic culture. Although it is unknown if it originated in Jewish or Islamic culture, Hebrew micrography was the creation of the Masorah scribes of Tiberias in the production of Bible codices (the book form of the Tanach that included marginal notes of the masorah and nikudot). The Leningrad Codice from 1009 written in Cairo, has sixteen diverse carpet pages presenting the small but fully legible masorah text in architectural and abstract designs surrounded by beautiful gold and red illuminations reminiscent of Middle Eastern carpets. This art form spread throughout the Levant, with Yemen as an especially important center, and then to north into medieval Europe. The Sephardic scribes of Spain utilized micrography, especially in some of the Catalonian Haggadot. The Ashkenazi scribes, with their micrographic specialty of medieval grotesques and bestiaries decorating the margins and front pages of luxury Bibles, and Haggadot also flourished from the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries. After the invention of printing in the mid-fifteenth century, the use of micrography expanded to ketubbot, omer counters, amulets, and other independent works on paper, eventually to its use in portraits and secular Jewish illustrations. Throughout the centuries it has remained a predominately Jewish art form. Much of this historical information is drawn from the research of Dr. Leila Avrin (1935 – 1999), to whom this exhibition is dedicated.

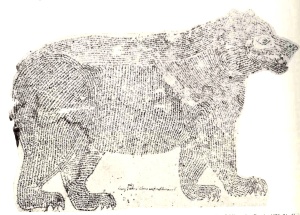

Pictorial micrography presents us with an entirely different phenomenon, as seen in the Megillat Esther by Hirsch Elia ben Leib Schlimowitz. Created in Lithuania in 1879, this folk-art bear takes the art form to a new level of creativity. The text has become totally secondary to the creation of the image of the bear, perhaps referring to the bear of Russia that always hovered over the affairs of Eastern Europe. The text panel (by curator Sharon Liberman Mintz) links this image with a verse in Daniel 7:5 that compares Persia, the setting of the Megillah, with the bear. Whether this is what the artist intended or not is almost beside the point. Rather what is striking is that micrography is used here to create an independent visual work of art.

The delightful Omer Calendar (1825) from Italy is another example in which the actual letters and words used have been rendered moot in the creation of the image of a deer about to feast on the tender new shoots of the budding tree, perhaps in anticipation of the approaching holiday of the giving of the Torah at Shavous. It is a perfect metaphor of the rejuvenation of Jewish Torah pursuits in the springtime of Omer counting.

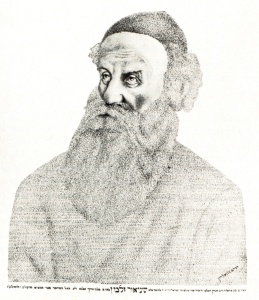

The portrait of Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Lyady created by Nathaniel Chasin in Washington, D.C. in 1924 is made up of text from the Tanya. While less interesting artistically, this work represents a reverence and piety for the founder of Habad that is truly inspiring considering the work and exactitude necessary to create this work. One of the most fascinating works in the exhibition, unfortunately not reproduced, is a Megillat Esther done in Corfu in 1782. The image is made up of the text of Esther and Parshas Zakhor and creates an eerie and powerful scene. Decorative columns frame a two-part center panel with a stark gallows and ladder on the left. Each rung of the ascending ladder is composed of one of the names of Haman’s sons. In the right panel Haman himself is hung in the miniature script. His face expresses shock and surprise as his hair flies up from the grip of the hangman’s noose. This depiction of an execution we all applaud has a beauty and conviction seldom matched in any depiction of this subject. The power of the text becoming its own image is amazing.

The art of micrography, old and venerable as it is, presents some unsettling problems. As early as the twelfth century, there was criticism. Rabbi Judah he-Hasid (1150-1217) complained that the designs render the text unusable and ordered that a patron commissioning a scribe to copy a Bible must instruct the scribe not to shape the masorah into any ornamental pattern (from curator Sharon Liberman Mintz). From the examples that have come down to us, not many listened to this sage. It is obvious that where the text is too small to be legible or too convoluted to make sense as text, holy words and letters are being made into abstract elements for some other purpose. Whether this purpose is to kosher a representational image or adorn a sacred document, is this proper use of divre kodesh? The fact that we as a people have utilized this art form for more than a thousand years up to today reveals both a comfort level with our holy texts in addition to the never ending need for visual images to express our Yiddishkeit in a myriad of ways.

Micrography: The Hebrew Word as Art

The Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary

3080 Broadway, New York, N.Y.