Maus: Flash Back to the Present

Survivor Memory into Holocaust Art, Part II

The Negative Heart of Maus

Last week we examined the first volume of Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, by Art Spiegelman. It is a complex and engrossing work that combines the testimony of a Holocaust survivor, the author’s father Vladek with Art Spiegelman’s process of telling the story in a “graphic novel” that depicts the Jews as mice and the Germans as cats. The two-volume work of close to fifteen hundred comic book style frames was published in 1992. Now we will consider the second volume.

The unstable core of both volumes emerges at the beginning of Part Two: And Here My Troubles Began. A fourteen page narrative set in the Catskills exposes the complexities of Artie’s relationship with his wife, Francoise, and his haunted dreams of “my ghost brother” Richieu. Vladek’s second wife, Mala, has left him and he desperately needs the company of his son. Then, just as the narrative about Auschwitz is about to continue, Vladek bursts out to his son; “But you understand, never Anja and I were separated… the war put us apart. But always, before and after, we were together… no so like Mala, what grabs out my money!” Just as he is about to recount the hellish entrance into Auschwitz, the pain of the loss of his wife years later by her own hand overcomes him. He is totally unable to find closure. The absence of Anja’s story, inexplicably lost by her own husband’s hand, is, according to James E. Young, a scholar on Holocaust representations, the “void at the heart of Maus… [its] negative center of gravity.” This becomes the emotional core that drives Vladek’s testimony and Spiegelman’s obsessive retelling of history and his own creative process.

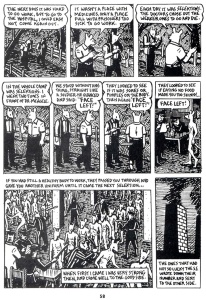

Time Flies (Chapter 2) reaches a climax of anxiety in an unbearable condensation of survivor testimony, painful contrasts with contemporary reality and the relentless process of creating Maus. The first page depicts Spiegelman slumped at his drawing table, reflecting; “Vladek died of congestive heart failure on August 18, 1982… in May 1987 Franoise and I are expecting a baby… between May 16, 1944 and May 24, 1944 over 100,000 Hungarian Jews were gassed in Auschwitz… In May 1968 my mother killed herself (She left no note.) Lately I’ve been feeling depressed.” Flies buzz around his head as the last panel on the page reveals him sitting amid piles of exterminated mice. It may be that there is more than one survivor to this tale.

Spiegelman’s depiction of his session with his psychologist, Pavel, also a survivor, examines the father/son relationship from yet another angle. Vladek as survivor is discussed along with the notion of the guilt of survival that a son might be made to feel because he didn’t have to face the camps. Finally Pavel muses that “the victims who died can never tell their side of the story, so maybe it’s better not to have any more stories.” Artie replies that “Samuel Beckett once said: ‘Every word is like an unnecessary stain on silence and nothingness.’” The next panel shows them siting in the silence that ensues until Artie exclaims; “On the other hand, he SAID it.” Here in most personal heart of Maus there is a fundamental questioning of the very project itself. But within a page we are thrust back into the life and death struggles within Auschwitz. The mechanics of the beatings, the selections, “the showers” and the ovens abruptly stop as we return to the kitchen table in Rego Park, Queens with Mala, Vladek and Artie.

The horror of the camps devolves into forced marches out of Auschwitz to Breslau and then a cattle car train to Dachau and further terrors of typhus and starvation. The remaining third of the second volume traces Vladek’s complex road after liberation. Again Anja’s story is referred to in uncertain terms; “When you were in Dachau, where was Anja? [Vladek answers,] I don’t know – to different camps… she marched from Auschwitz earlier as me, and came also through Grossrosen, and then – I don’t remember…” The very limits of the survivor Vladek’s memory becomes the boundaries of the lost story of Artie’s mother. Rather pointedly the narrative continues to incorporate intensive shifts between post war Europe, the DP camps, killings of Jews in Poland and Vladek’s attempts to assemble a post-war life, a stint in Florida and his worsening heart condition.

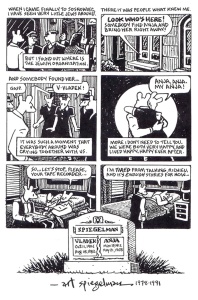

Returning to the past, the narrative attempts a kind of closure as Vladek learns that his wife Anja is alive, probably in their hometown of Sosnowiec. Vladek sets off for Poland and the last page documents their reunion. As the frame shows them embracing Vladek reports “More, I don’t need to tell you. We were both very happy, and lived happy, happy ever after.” The terrible irony of his testimony at this moment, knowing that she commits suicide twenty years later, haunts us just as it has haunted father and son throughout Maus. Spiegelman attempts to put it all to rest in the last frame of the double tombstone for Vladek and Anja over his own signature, dated 1978–1991, the wrenching years Spiegelman worked on the book.

Suspended Over the Abyss

Art Spiegelman’s Maus: A Survivor’s Tale achieves the ultimate dislocation on the final page. The last two frames return us to Artie recording his father’s testimony, the ostensible subject of the entire book. Vladek is exhausted, saying, “I’m tired from talking, Richieu, and it’s enough stories for now…” as he rests his head on the pillow. By addressing Artie as his dead son Richieu, the child that was an actual victim of the Holocaust, Vladek spreads victimhood beyond survivors to their descendants. The act has enormous resonance. The recognition that we are all victims, at least in an existential sense, is literally exhausting, and demanding a certain kind of silence of the stories. This silence is necessary for life to be allowed to go on but paradoxically the silence cannot be permitted because we understand that the future must be inoculated by the memory of the past.

Maus represents a crucial stage in the evolution of Holocaust memory. It is rooted in the bedrock, the legitimacy and moral authority of Vladek Spiegelman’s experiences. This he shares all survivors. The process of transmission from father to son by means of a disjunctive medium removes the testimony from the purity of his own voice, which is nevertheless preserved in tape recordings Artie made of many of their sessions. His authenticity seeps through the imposition of Artie’s drawings even as the commix art combines images, text and visual juxtaposition between disparate times and places. No mere conversation could accomplish this. The extreme breaks between the several narratives, especially in the second volume, reveal a new kind of testimony that is concerned with an untold story, that of Anja, mother and wife. Because we can sense her presence, albeit only by absence, even in the last frame, she too becomes included as a survivor.

Holocaust memory, the irreducible core of Holocaust history, has been transformed in Maus into Holocaust art. This process has two possible consequences. It can signal a kind of desperation, an acknowledgement that with the passing of the last of the survivors we will no longer be able to speak with authority about what may be the defining event of the twentieth century. Or Maus may signal that it is exactly within this new modality of Holocaust art that we are able to address complex realities concerning the Holocaust inconceivable within the purview of mere history.

Note: I gratefully acknowledge insights from At Memory’s Edge by James E Young and published by Yale University Press, 2000.

Maus: A Survivor’s Tale

Volume One: My Father Bleeds History

Volume Two: And Here My Troubles Began

By Art Spiegelman, published by Pantheon Books, New York 1992